The Late 1920s to World War II

Like the desert flowers in the spring, the two-score or more of towns that formed in the wake of the heat and excitement of the Bullfrog boom seemed to appear almost overnight out of the rocky soil-only to disappear nearly as quickly. Each town's emergence was heralded as the beginning of something important, and at the time, it seemed as though all would last forever. Would not such names as Bullfrog, Gold Center, Pioneer, Leadfield, Chloride City, Carrara, Leeland, Lee, Rose's Well, Springdale, Bonnie Claire, Amargosa, Gold Crater, Johnnie, and others become permanent fixtures on the map of the American West-as solid and as enduring as the stone for which the area's mother camp, Rhyolite, was named? It was not to be. The veins of precious metal in the barren mountains that fed each town were as thin and unpredictable as the desert rains that watered the blossoms of spring. Like the flowers, the towns would not endure long. They would have their colorful moments in the sun, and then they would disappear into the rocky desert soil from which they sprang.There was one exception: Beatty. As the other towns faded, it hung on. Situated about half-way between Las Vegas and Tonopah on the main north-south roadway in Nevada, and with plenty of readily accessible water, Beatty, though it remained small, became the economic nucleus for a vast area that encompassed more than 50 miles in any direction in southern

Nevada and the eastern California desert region

Economic activity in Beatty in the late 1920s and early 1930s included some mining, an assortment of local merchants, the distribution of oil and gas, the construction of Death Valley Scotty's Castle during the late 1920s, and the production and sale of illegal alcohol during Prohibition.Mining Slacks Off

There were only a few mines in operation in the area-at Pioneer and Rhyolite - during the early part of this period: Rube Bryan owned the Mayflower Mine in Pioneer; Louis McCrea, a member of a prominent Beatty family, came to the area in the Rhyolite days and worked his mine at Chloride Cliff. for years; and J. I. Crowell, Jr., operated his fluorspar mine on Bare Mountain (J. and M-K. Crowell, 1987; A. Revert, 1987; R. and C. Lisle, 1987). But sometimes people who were not even miners often stumbled on ways to make a profit from a mine. Tailor Bill Elliot's connection to the profits of the Gold Ace Mine is one of the most unusual Beatty tales.The Gold Ace Mine, located on the west side of Bare Mountain, not far from Carrara and several miles south of Beatty, was discovered in the early years of the Bullfrog boom. At times, the mine produced some very rich gold ore, but production was often "on and off" because to the "pockety" character of the ore's occurrence. In March 1929, Roland Wiley, a young lawyer who was living in Las Vegas and later went on to become district attorney for Clark County, rode from Las Vegas to Reno with Bill Elliot, who had owned a tailor shop in Los Angeles. Elliot had operated tailor shops in Tonopah and Goldfield during those town's boom days and had intended to open another shop in Reno. Elliot was very well known for his craftsmanship and had won a national award for a coat he made.

On their way to Reno, Wiley and Elliot stopped at Carrara where they learned from Briz Putnam and Jim Shay, two former Tonopah and Goldfield miners who were in charge of the Gold Ace Mine, that things were not going well. No good ore was in sight and Gold Ace stock was worth only 3 cents per share. Not long after Elliot opened his Reno shop, Harry Stimler, codiscoverer of the rich strike that resulted in the Goldfield boom in 1902, talked Elliot into trading him two tailor-made suits for 5000 shares of Gold Ace stock. Elliot agreed; at the stockmarket price he would receive the equivalent of about $75 each for the suits, a fair price for a tailor-made suit at that time.

Late that spring, however, fortune changed at the Gold Ace when a pocket of very rich gold ore was found. There was considerable excitement associated with the discovery of the rich ore, and a man named Bixby, a member of a prominent Long Beach, California, family who had invested in the mine, chartered a promotional train from Los Angeles to Beatty to publicize the good luck and to help move the stock's price up. Roland Wiley came up from Las Vegas to Carrara to participate in the festivities, which were timed to coincide with the July 4 celebration. A big tent had been set up, plenty of alcoholic beverages were available, and samples of the ore, in which free milling gold could clearly be seen, were on display. As a result of the discovery of the ore the price of the Gold Ace stock temporarily shot up. That summer Elliot sold the 5000 shares of Gold Ace stock he had obtained from Stimler for more than $1 a share, thus making Stimler's suits the most expensive in the state of Nevada (Wiley, 1991).

By the late 1930s, mining activity in Beatty had increased somewhat in comparison to the level of a few years earlier. The Roosevelt administration had raised the price of gold, which stimulated a number of small operations in central Nevada. As the only community of consequence in a vast area, Beatty was a natural trade center for the miners. Ralph Lisle remembered the mining activity at Skidoo and Pioneer, with 20 or 30 men working at Bullfrog and a few less at Rhyolite. There was also activity at other area mines-the Keane Wonder, the Chloride Cliff., the Ubehebe, the Gold Ace, the Panama on Bare Mountain, and the Diamond Queen; in 1940 the payroll at Carrara frequently reached 200 (R. and C. Lisle, 1987; "Beatty Shows Population Growth in Past Decade," 1950).

The Reverts Boost the Beatty Economy

The Revert family was typical of many that came to Nevada and made contributions to the economy. Albert Revert, patriarch of the Revert family of Beatty, was born in Le Havre, France, September 20, 1869; when he was a small child, he immigrated to the United States with his family. The Reverts first lived in New York City, but when Albert's mother died, he and his father made their way to San Francisco and later to Virginia City, where young Albert attended the Fourth Ward School. At age eleven he found a job working in a box factory in nearby Verdi, and he lived with a French family there (A. Revert, 1987).In Verdi, young Albert worked hard and prospered. But even as a child, he did not like working for other people. He worked in sawmills and also began to buy fresh fish from the Indians in the Reno area for shipment on ice to the Palace Hotel in San Francisco. He acted as an interpreter for the French Canadians in the Verdi area (A. Revert, 1987; R. Revert, 1988). Albert moved to Tonopah shortly after the great silver boom began in 1900. By this time, Revert had mastered every aspect of the lumber business, and he established a lumber yard on the north side of town at the site of the old Conley Yard. His Tonopah Lumber Company (which owned a large number of horses, mules, and wagons) hauled lumber from Mina to Tonopah prior to construction of the railroad. It was one of several firms that transported supplies. In all, 400 horses in teams of 12 to 20 were involved (Myrick, 1962:237). Revert married Henrietta Bucking, a San Francisco woman whose parents had come from Germany. Their first child, Art, was born in San Francisco in late 1905 and shortly thereafter-not long after the great San Francisco earthquake-mother and baby joined Albert in Tonopah. The family resided in Tonopah for several years, until Art and his mother moved back to the San Francisco area. Art completed high school in Oakland, California. Meanwhile, the family had grown to include three additional children, Edith, Norman, and Robert (A. Revert, 1987; R. Revert, 1988).

Albert eventually became the owner of a large sawmill in Verdi and a string of lumber yards in virtually every community of consequence in Nevada, including Fallon, Sparks, Elko, and Reno. With profits from his Tonopah Lumber Company, Revert purchased the Verdi Lumber Company in 1908 from Oliver Lonkey. Originally there were several partners in the Verdi firm, including Jack Salisbury; but by the late 1920s, Revert was sole owner. In addition to wood products, he sold hardware, wagons, and automobiles. He owned no lumber yards in the southern part of the state because there was little business activity there at that time. These widely dispersed business holdings were blessed with honest and competent help who did not require constant supervision or oversight (A. Revert, 1987; R. Revert, 1988; Myrick, 1962: 411).

After completing high school, Art joined his father in the lumber business in Verdi, working at general duties, including grading lumber. Times were good for the company. There was considerable business in the production of doors and sashes and molding for decorative trim. The pine wood from the region was especially suited to such uses because it did not crack or split when a nail was driven through it. One of the biggest markets was New York. Often, several railroad cars loaded with the company's products were in transit, necessitating large amounts of credit. Things went well until a few years before the Depression (A. Revert, 1987).

A number of serious fires proved to be the company's undoing. There was one during World War I, which was believed to have been set by a German agent. Another fire in the 1920s was caused by a whirlwind that scattered hot coals over the mill area. The most serious fire (in 1926) burned the entire Verdi sawmill. Robert Revert remembered the 1926 fire and recalled that the hill behind Verdi was red with flame. (Only in recent years have the trees begun to grow back.) Revert had recently cut all the timber he was planning to mill that season, and he asked the Forest Service to let him out of his contract because of the fire, but his request was refused. A modest mill was assembled, but it was not enough; the company went bankrupt, in part because of inadequate insurance (R. Revert, 1988).

After the Reverts' lumber business was wiped out, the family looked around the state for, as Art said, "a place to land." Albert and son Art arrived in Beatty on New Year's Eve, 1929. They chose Beatty because a mine at Chloride Cliff looked promising. Albert had purchased a Chloride Cliff property (not the same property that J. Irving Crowell, Jr., had worked) in partnership with three men-W. R. McRae, a man from Reno who was the owner of the Overland Hotel, and an ex-governor of Idaho. The unexpected deaths of two of the three investors led to the failure of the enterprise (A. Revert, 1987).

Revert then decided to purchase the Shirk estate from Shirk's daughter, for approximately $10,000. The estate included the old Beatty Ranch, consisting of 300 acres, the stone cabin once occupied by Old Man Beatty, and considerable water rights; a primitive community water system that obtained water from the Beatty Ranch and supplied it to a small number of town residents; a number of pieces of property in town; and a store, known as the Amargosa Land and Cattle Company (sometimes called Palmer's Store, after a former owner), housed in a large, iron-clad building at the north end of town (A. Revert, 1987; R. Revert, 1988). The store, renamed the Revert Mercantile, was the largest in town. It carried anything a person in an isolated desert community could possibly need: a variety of canned goods; fresh meat that was shipped in by rail from Ottumwa, Iowa; mining supplies, including picks, shovels, drilling steel, and dynamite and caps (that were stored in a powder house on the hill east of town). Revert did big business in the sale of coal, which was brought in on the railroad by the carload and sold by the sack.

The Reverts had acquired the Union Oil distributorship shortly after they arrived. They built a Union Oil service station in town and soon had gas pumps in Rhyolite, Gold Point, Ash Meadows, Hot Springs, and Springdale; these locations required only a tank and a visible pump, which sold for $35 or $40. At Rhyolite an old caboose and pump served as the service station. The Revert trucks made deliveries to the pumps, and the local owners bought the gas at wholesale prices. There were three problems with being in the petroleum business in Beatty, Art Revert recalled: bad roads, long distance, and the difficulty of collecting money (A. Revert, 1987).

One of the first things the Reverts did after their purchase in 1930 was to upgrade and improve the primitive water system that was part of the Shirk estate. They patched pipe and extended distribution to additional families in town. The charge for water service was $4 a month per customer (A. Revert, 1987).

Some years later State Health Department officials analyzed water being supplied to Beatty. Their analysis revealed excessively high levels of fluoride in the water obtained from the spring on the Beatty Ranch. (The water stained the teeth of children; Art Revert remembered that the teeth of the Indian children were especially stained.) State officials found the water quality unacceptable, and the Reverts turned their operation over to the Beatty Water Company, which was owned by a general improvement district. The company dug a well on the edge of the ballpark between Third and Fourth Streets and piped in additional water from wells drilled in the hills to the west of Beatty; this source diluted the fluoride in the water from the ballpark well. Water from those wells became the source of community water (A. Revert, 1987). In May 1953, Albert Revert, who in his later years became known as "Dad," passed away at the age of 83. His obituary in the Beatty Bulletin described his birth in France, his residence in Virginia City, and the eventual establishment of the lumber company in Verdi. It described how Revert had first arrived in Tonopah, his skill in handling 22-mule teams over rough trails, and in making complicated driving maneuvers. "Always a great booster for his community," the article stated, "and the State of Nevada, Mr. Revert had a wealth of friends who looked forward to visiting him at every opportunity. His ready wit and keen mind never deserted him, and he maintained his interest in national and world affairs to the end" ("Beatty Mourns Passing of Beloved Dad Revert," 1953).

Robert Revert described his father as a self-educated man with a keen insight, an observant individual with a fast mind, and a man who did everything for his family. He also added that Henrietta Revert, who was fluent in three languages-English, French, and German-had an "even disposition and was a good cook, seamstress, bookkeeper, and was a wonderful mother" (R. Revert, 1988).

Other Economic Activity

In addition to Revert Mercantile, there were two other stores in town: one owned by the Richings family (operated by "Mom" Richings) and the other by Cy Johnson. H. H. ("Pop") Richings operated the Standard Oil dealership. Beatty had its share of bars, including the Gold Ace, St. Peters' Bar (run by Glen St. Peters), and the Exchange Club (originally built and still being run at that time by George Greenwood). The Gold Ace burned down about 1940-many residents remembered the fire. Joe Andre's Silver Diner and a fountain in the Exchange Club were popular restaurants (R. and C. Lisle, 1987; A. Revert, 1987; C. Lisle, 1989).The T&T Railroad employed several townspeople in Beatty. Before the roads in and out of town were paved, nearly all goods came into town from the south on the railroad. Dave Aspen was then the railroad agent; he had originally worked in Tonopah for the railroad (A. Revert, 1987).

Lisle Contributes to Beatty's Transportation Economy

The widespread availability of the automobile added a new dimension to transportation and economic activity in southcentral Nevada. Though the automobile clearly had its advantages in the area, the conveniently scheduled railroad service at first provided stiff competition to the horseless carriage as the mode of travel between the region's widely separated towns. However, as railroad schedules were first reduced and then eventually eliminated entirely, the automobile came into its own. It emerged as the transportation means of choice (the only other alternatives were foot, horse or burro, and wagon). The growing popularity of the automobile created new economic opportunities in Beatty as well as other communities. Service stations-as they were properly termed in those days-were opened to meet motorists' needs for gas, tires, repairs, directions, and a friendly word. Service stations gradually became an important factor in Beatty's economy and continue to contribute significantly to the area.The automobile and the service stations it spawned represented a change in the way people lived and the way they thought about life and the world, but not everyone saw the advantages, including some of the old "jackass" prospectors. In his book 50 Years in Death Valley-Memoirs of a Borax Man, Harry P. Gower tells of a chance meeting he and William W. Cahill (both officials with the Pacific Coast Borax Company, which owned the T&T) had with an old-timer who was having difficulties with his preferred means of transportation. The old-timer exhibited an intuitive grasp of the close link between transportation mode and lifestyle: I might as well tell of the time [W. W.] Cahill and I were driving along in a Model A Ford towards Goldfield 40 miles away. We stopped to chat with an old prospector who was having some trouble packing up his burros. He had been heading towards Goldfield too, but his animals had broken loose and only just been rounded up after a three-day chase. Cahill said, "Shucks, why don't you get rid of those damn troublemakers? Get a Ford and you would be in Goldfield in two hours." After thinking that over the old man said, "I guess you're right but what would I do when I get there?" (Gower, 1969:138).

The old prospector knew getting there was most of the fun. Nonetheless, the automobile was clearly here to stay and many, including Ralph Lisle, saw economic opportunity in its arrival. Ralph Lisle, the son of John Quincy and Celesta Fair-banks Lisle, was the grandson of Ralph J. "Dad" Fairbanks, a southern Nevada-Mojave Desert pioneer and town builder. Lisle was born in Fernley, Nevada, in 1914, but spent most of his life in the Beatty-Death Valley area (R. and C. Lisle, 1987).

Lisle has vivid memories of the move his family made in 1926 from their family homestead in Fernley, just east of Reno, to Clay Camp in Ash Meadows in the Amargosa Valley. They caravanned in a Model-T pickup and a Dodge touring car on dirt roads for three days. On the first leg of the journey, they drove from Fernley to Yerington and then on to Schurz, where they spent the night. The next day they drove to Goldfield. (Because the highway followed the railroad tracks, they bypassed Tonopah on their way to Goldfield.) They spent the night at the Goldfield Hotel, which was a treat to the impressionable young Lisle. The next day they drove through Beatty to Clay Camp (R. and C. Lisle, 1987).

After Ralph Lisle graduated from high school, he worked for two years for his grandfather, 'Dad" Fairbanks in Baker, California, and for seven years for his uncle, Charlie Brown, in Shoshone, California. Working for Fairbanks and Brown amounted to a quality apprenticeship in the management and operation of gas stations and general stores in the Death Valley region. In 1938, Brown sent Lisle to Beatty to reactivate the Standard Oil distributorship, which had closed down early in the Depression, and the service station that they had recently purchased from H. H. Richings. (The other distributorship-Union Oil-was owned by the Reverts.)

Lisle and his wife, Chloe (whom he had married in 1939), operated the station until the outbreak of World War II, when both the distributorship and station were deemed a nonessential industry and were forced to close. Lisle switched to the mining of minerals, which was considered essential for the war effort. Later he entered military service. After the war, he returned home and found that the ownership of the Standard Oil distributorship had been transferred in his absence. Later, the Lisles opened a Union 76 station on Second Street across from the Exchange Club.

The Bootleg Business

Perhaps the most important business in the Beatty area during Prohibition was illegal: the production and distribution of homemade booze. In fact, the bootleg business was so active in Beatty that, as one old-timer said, "You could smell the town coming." Many residents made their own beer.The Beatty area bootleggers used sugar rather than grain in their manufacturing process, and much of the sugar was purchased at the Revert Mercantile. Distilleries were fired with kerosene, again purchased locally. Both the sugar and kerosene came into town on the T&T Railroad. There was "spirited competition" among the area's producers concerning who made the best whiskey; but even the best produced then, old-timers say, was not good whiskey by today's standards. The product was sold in bottles, jugs, barrels-anything that would hold liquid. It was sold as far away as Ely and California. Some was sold in Death Valley (A. Revert, 1987).

Law enforcers were a constant problem for the bootleggers, but some authorities were known to look the other way. Local producers were usually tipped off if federal officials were heading for Beatty. Word would come in over the telegraph: "The blackbirds are flying today." It was deemed necessary to provide law enforcement officials with token arrests, so producers and sellers took turns at getting "knocked off." Those arrested would go before the court and be fined, but would quickly be back in business. A minor era in Beatty's history ended when Prohibition was repealed in 1933 (A. Revert, 1987).

Scotty's Castle: "Neither of Us Pays Rent"

Construction of Scotty's Castle, which began in 1925, had a notable effect on Beatty, the closest town to the site. Walter Edward Scott, better known as Death Valley Scotty, was born in Cyanthiana, Kentucky, on September 20, 1872, and came to Nevada at the age of fourteen; he became skilled as a cowhand and at bronco busting. After a stint with Buffalo Bill Cody's Wild West Show, he ended up in the Death Valley area where he put his greatest talents to use-as a quintessential flimflam man. Richard Lingenfelter described Scotty as "a ham actor, a conscienceless con man, an almost pathological liar, and a charismatic bullslinger" (1986:242).Scotty would do almost anything for attention and publicity and could pry a dollar out of the most tight-fisted businessman. Scotty's Castle -probably his greatest con-involved Albert M. Johnson, a wealthy capitalist from Chicago. Johnson, the son of an Oberlin, Ohio, banker, had graduated from Cornell University in 1895. He began amassing his own wealth by speculating in the Missouri zinc mining boom with money borrowed from his father. He eventually acquired control of the National Life Insurance Company in 1902 (Lingenfelter, 1986:256). An article in the Beatty Bulletin gave Scotty's version of how he persuaded Johnson to underwrite the construction of a great mansion at the mouth of Grapevine Canyon at the north end of Death Valley.

I always wanted a castle in Death Valley, so one time, several years ago, when I was in Chicago I thought I'd see about getting it. I noticed a huge skyscraper and asked a policeman who owned it.

"That belongs to a big insurance company," he said. I asked him who the head man was, and he replied, "The president, of course, A. M. Johnson."

So I got in the elevator and rode to the top floor where I asked for Mr. Johnson. He was very cordial, and inquired, "What can I do for you, young man?"

"I live in the desert and want to build a Castle," I told him. "I figure it should cost about a million and a half dollars. I thought maybe you'd give it to me."

"Why, of course," Johnson said, going to his safe. Then he stopped and remarked, "I'm not sure a million and a half is enough. Better take two million."

"So I took the two million and came out here and built the Castle," Scotty concluded straight-faced ("District Loses True Friend in Death of A. M. Johnson," 1948).

The castle, called "one of the wonders of the world," was featured in the Saturday Evening Post, and for 18 days stories about it appeared on the front page of the Los Angeles Record. The castle became so famous that it even upstaged Scotty, who refused to sleep in his $40,000 bedroom in the castle, preferring a small bungalow several miles down the canyon, or if the Johnsons were not there, sleeping on a cot amid dirty dishes and pans in the kitchen (Lingenfelter, 1986:461-463). The mansion, located in the middle of nowhere, had its own water supply, sewer system, hydroelectric generator, cold storage, ice plant, air conditioning, and solar heating. Interior work was accomplished by European artisans and craftsmen. Johnson furnished the building with custom and antique items obtained from extended buying trips. When it was completed, the castle boosted Beatty's economy by becoming a major tourist attraction (Lingenfelter, 1986:448, 462).

As Lingenfelter (1986:461) has pointed out, Death Valley Scotty was the personification of Death Valley for many years, a major attraction in himself, as fascinating as the mountains and the valley whose name he bore as a nickname. Scotty had always had a flair for cultivating publicity. Though Johnson put up the estimated $2.5 million for the castle, Johnson was more than content to let Scotty give the world the impression that it was Scotty's, constructed with Scotty's millions.

.. . the story is told of the persistent tourist who wanted to know definitely who owned the Castle, Johnson or Scotty. Ever a master of evasion, Mr. Johnson replied: "Well, my friend, it's like this. Scotty lives here and I live here, and neither of us pays rent" ("District Loses True Friend in Death of A. M. Johnson," 1948). In January 1948, when Johnson died, the Beatty Bulletin reported, "In Mr. Johnson's death, the West, and particularly this district has lost a loyal friend." The story continued. Scotty did not attend Mr. Johnson's funeral fearing that he might break down under the strain, for the desert philosopher is a man of advanced years himself, and will mark his 76th birthday on September 20. Scotty was present at funeral services for Mrs. Johnson several years ago, and was so moved that he reportedly told his partner at the time that he would never go through a similar ordeal.

"I prefer to remember Johnson as he was in life," Scotty said simply ("District Loses True Friend in Death of A. M. Johnson," 1948).

Johnson's body had been in the ground scarcely more than four months when a new facet was added to the incredible tale. The Beatty Bulletin ran the following article.

SECRET GOLD HOARD

HIDDEN AT CASTLE?

NO TRACE FOUND OF RICH CACHE

OWNED BY JOHNSON

What Happened to 7500-oz Gold Dust

Treasure Trove After Johnson Died?

A secret cache of over 7500 oz. of gold dust valued at about a quarter of a million dollars, remains unaccounted for in the will and behests of A. M. Johnson, wealthy Los Angeles philanthropist and religious zealot, who died last January. . . . The possible existence of the modern "pot of gold" was disclosed by Walter Scott (Death Valley Scotty) and confirmed by executive personnel of Scotty's Castle, some 60 miles from Beatty and Goldfield, who said that they knew of the treasure trove before Johnson's death but had no inkling as to its present whereabouts.

Scotty avowed that two years ago Johnson made a trip to his ranch, located a short distance from the Castle, and produced several bags of almost pure gold dust which he had accumulated through the years. Where it came from Scotty could not say, and Johnson was reluctant about telling him.

The two men secretly weighed the precious material, finding that it totalled slightly over 7533 oz., according to Scotty. Later, Johnson mentioned the matter to Mr. and Mrs. Henry Ringe, who managed the castle, and indicated that he was puzzled as to how he would ultimately dispose of the gold.

Johnson, a meticulous man, had carefully provided for the disposition of virtually every article of his worldly goods before his death, but nowhere was there any mention made of the quarter of a million dollars worth of gold dust, Scotty said.

Since Johnson had customarily taken him into his confidence on matters of importance, Scotty is puzzled to know what became of the treasure, and indicated that he had conducted private searches in the Castle and around the grounds without unearthing any clues. He appears to believe that Johnson secreted the gold somewhere in the neighborhood, "but died sooner than he expected."

Sometime last summer, while low in spirits, Johnson again mentioned the rich hoard to Scotty, and seemed as perplexed as ever as to what he should do with it. He vaguely made mention of taking it to Mexico, Scotty said, but whether he ever did or not Scotty could not say ("Secret Gold Hoard Hidden at Castle?" 1948).

The alleged cache of gold would have weighed more than 627 pounds, no easy task for an old man to stash alone. At 1991 gold prices, it would be worth more than $2.75 million. Six years after Johnson died, in January 1954, Walter Edward (Death Valley Scotty) Scott, died. In the obituary in the Beatty Bulletin, Scotty was described as one of the last remaining links with the early West: "Death overtook him on Nevada soil, where in his younger days he wrote so many colorful chapters in the state's history." Scotty is buried on a hill near the castle that bears his name ("Scotty Buried on Hill Near Famed Castle," 1954).

People of Beatty

The people who called Beatty home came from many places, led a variety of lifestyles, and brought to the community their unique personalities and talents. All left their mark on Beatty.Swiss-born Caesar Strozzi was struck with "gold fever" and migrated to the United States; for a time he worked in Rhyolite. His wife, Mary, was a full-blooded Western Shoshone and a member of the Te'moak Band, which lived in the Elko area. The couple and their seven children did not reside within the Indian community on the east side of town, but lived in the south part of Beatty (Gillette, 1987, 1989).

In the 1920s Strozzi homesteaded at Briar Spring, north-west of Beatty, in the Grapevine Mountains. He constructed a home and several outbuildings-five buildings in all in addition to dugouts (Latschar, 1981:230). The Strozzis, who spent about half of the year at Briar Spring, would usually leave for the ranch in early May and seldom returned to Beatty before the latter part of October. Strozzi cultivated a variety of crops on the ranch, primarily for his family's consumption. Irrigation was needed to produce corn and vegetables as well as apples, pears, and peaches. Strozzi also raised some chickens and cattle. The cattle were usually rounded up in the winter and moved down from the high country because of the cold weather. The ranch was occupied by Strozzi until the late 1940s. Caesar Strozzi died in 1953 and his wife, Mary, passed away in 1963. Dolly Gillette, one of the Strozzi children, still resides in Beatty (Gillette, 1987).

Grace Whitten Davies arrived in Beatty in 1937 and married Fred Davies, who had previously lived in Ash Meadows and had moved to Beatty a few years earlier (Davies, 1987). Fred worked as a blacksmith and Grace was a waitress.

Joe Andre, a musician who had a dance band, played in Beatty and other small towns throughout Nevada during the 1930s. He pulled his well-constructed travel trailer with aluminum siding to the dance sites. When the dance band folded, Andre set the trailer up on a lot diagonally across from the Exchange Club in Beatty and operated a cafe called the Silver Diner. In the 1940s Andre acquired the Exchange Club from the Greenwood Estate and ran it for several years before turning it over to his son-in-law, Louis Hinds, who managed it for several years before Andre sold it to Warren Doing (R. Lisle, 1991).

During the 1920s and 1930s Beatty was home to an assortment of elderly, retired miners who had come to the district with the Bullfrog boom and had stayed on. Many were former members of the International Workers of the World (Wobblies) labor union, and though their names are now forgotten, they are best remembered for their outspoken leftist political beliefs.

According to the U.S. Census for 1940, Beatty was still quite small. The population of the township, which included those who lived in the area from Springdale, located at the head of Oasis Valley, to Lathrop Wells, now known as Amargosa Valley, was 450; most lived in Beatty ("Beatty Shows Population Growth in Past Decade," 1950). Ralph Lisle remembered there was no housing-not even a trail-west of Montgomery Street, "just sagebrush and rocks." Quite a number of houses had been moved in from Rhyolite and Pioneer. Big cottonwood trees lined the wooden sidewalks of Main Street, and the fronts of many buildings had canopies. The trees, the canopies, and the wooden sidewalks were removed during the 1950s when the State Highway Department paved the road through Beatty and widened it in the process (A. Revert, 1987; J. and M-K. Crowell, 1987).

Electric Power and Waste Disposal

Until about 1940, Beatty had no electricity. The first supplier, Jim Mardis, obtained a franchise and provided a few families with electricity (C. Lisle, 1989). This system frequently broke down, never ran on a regular schedule, and could not be depended upon for refrigeration. About 1940, the Reverts obtained a government loan, bought out Mardis, and expanded the system. The new supplier, known as the Amargosa Power Company, bought four big International diesel engines equipped with 50-kilowatt generators, scrounged the desert for poles, and wired the town (Sternberg, 1986). Any-body who wanted electricity could sign up. The availability of electricity in Beatty allowed many people to purchase refrigerators. In 1950, street lights were installed in Beatty, first on Main Street and then on some of the side streets. Prior to that the only light after dark was from shops and stores open after sundown (A. Revert, 1987).The four new engines were more than enough to handle the town's requirements. The system could get by much of the time on one engine and a heavy load required two. Occasionally a third engine was required, but four were never needed, leaving a reserve in case one failed. The extra engines did not kick in automatically upon increased demand, but had to be engaged manually. Art Revert had gauges installed in his house and could determine the need at a glance. The system ran 24 hours a day and required little maintenance-only twicedaily checks and periodic oil changes. The Amargosa Power Company operated until April 1963 when the Nevada Public Service Commission approved its sale to the Valley Electric Association, an electric cooperative serving Pahrump and Amargosa valleys; the power was generated at Hoover Dam. Service with Valley Electric began with 194 customers in Beatty and 6 in Rhyolite (Sternberg, 1986; A. Revert, 1987; Records, 1987).

There was no community sewer system in Beatty as of 1949; nearly everyone had a septic system. Eventually there were so many septic systems that the groundwater was becoming contaminated. In the 1970s, a sanitation district was formed to put in a communitywide sewer system.

Phone Service

Communication with the rest of the world was late in coming to Beatty. A telegraph line served the town while the T&T was operating, but when the railroad shut down the line was removed. Fairly early during World War II, phone lines were strung from Las Vegas. Crowells' fluorspar mine, deemed an essential industry by the federal government, helped Beatty get a high priority, AA-1 rating, for the installation of phones. There was a switchboard in town and the operator was in Tonopah (J. I. and D. Crowell, 1987).Eavesdroppers on the party line were sources of amusement. Before they were married, Maud-Kathrin Crowell re-called talking to Jack on the phone from her home in Boulder City. She heard a chiming clock strike the hour. "Your clock is fast, Jack," she said. "I just heard it strike the hour. It isn't 8:00 yet."

"We don't have a chiming clock," Jack replied.

They both heard a click on the party line (J. and M-K. Crowell, 1987).

But even in the late 1940s, it was still quite difficult to reach people in Beatty by phone. There were only two phones: a public phone in Brownie's Store, which was closed in the evening, and another in front of Azbill's Store (formerly the Revert Mercantile), where street noise and the phone's distance from homes made it difficult to use. A campaign was begun for installation of a public phone that would be "readily available at all times for both incoming and outgoing calls" ("Continue Efforts to Secure 'Night' Phone for Beatty," 1948). By the late 1950s, there were approximately 30 phones in Beatty (J. and M-K. Crowell, 1987). In about 1960 a modern dial phone system was installed (C. Lisle, 1989).

Pioneer Educators

In 1937, Ert Moore, a young school teacher, came to Beatty looking for a new job. His first position in Nevada, which he had held for two years, was at Deerlodge, an isolated area about 30 miles east of Pioche in Lincoln County (Moore, 1979:1-9). In 1937, when the enrollment fell to two students, Lincoln County closed the school. Hearing that teachers were needed in Goldfield and Beatty, he and his wife set out for Ely, then Tonopah, "over unpaved roads across sandy stretches when the car running boards would drag on the sides of the ruts" (Moore, 1979:17). They arrived in Goldfield only to find that the last vacancy had been filled. They hastened on to Beatty and found there was a vacancy. Moore met with the members of the school board-George Greenwood, who owned the Exchange Club along with an attached garage and grocery store that also included the post office; Tom Harris, who operated the Associated Gas Station and Garage located on Fourth and Main; and Bill McClosky, a miner from Idaho who had come to the Beatty area during the Rhyolite boom and operated a mining property at Chloride Cliff. during the 1930s (R. Lisle, 1991).A contract was drawn up; Moore's salary was to be $160 a month, a substantial increase over the $900 a year he had received in Lincoln County. Moore taught in Beatty for five years before moving to Gabbs in 1942 (Moore, 1979:17, 38, 40; C. Lisle, 1989). While he was employed in Beatty, Moore and his wife lived in a three-room miner's house that had been moved there from an abandoned mining camp, possibly Rhyolite.

Moore, who spent more 25 years as a teacher and educator in Nevada, described the Beatty school:

The elementary school consisted of two rooms and toilets, and four grades were taught in each of the two rooms. This building was old but very sturdily constructed. The high school building consisted of a one-room structure brought in from some old mining camp. The dimensions of the building were about 12' x 20' and there was only one door. Heat came from an oil stove near the door, and the stove was between the students and the exit. . .. Playground equipment consisted of one backstop and goal for basketball for the older students and nothing for the younger ones to play with (Moore, 1979:19).

Old maps hung on the walls; when extra desks were needed, they could be obtained from Goldfield for $2 each (Moore, 1979:28). There were 10 students in the high school; 2 were Anglos and the rest were Indians. Of the 40 students in the elementary school, about 25 were Indians (Moore, 1979:20).

One Beatty resident remembered her first day at school after moving to Beatty from Los Angeles. Finding only about 3 children in her class, she was struck by how small it was in comparison to the schools she had attended in Los Angeles. "Is this all the kids?" she recalled asking her teacher.

The teacher replied, "Oh, no. Wait until the Indian kids come." They were out of town harvesting pine nuts.

In 1938, Fred Dees was hired to teach the upper grades. Dees was a mature and experienced teacher, and even today his former students speak fondly of him and credit success in college to the excellent education they received in his classes Q. and M-K. Crowell, 1987).

Moore described how he and Dees secured materials to construct some much-needed playground equipment for the younger children:

We needed playground equipment first and no money was available. The old poles from a defunct telegraph line to Goldfield were still in place. Local information was that Death Valley Scotty owned them. I left word at the saloons that when Scotty came to town to tell him to drop by the school. One day he came chugging up in the old car that is on display at Scotty's Castle in Death Valley. I asked for enough poles to make playground equipment, which he so generously granted. He invited me to bring the family and visit him at the castle, which we did. Mr. Dees and I went to the pole line, secured our poles and made the necessary playground equipment, which was greatly enjoyed by the children.

In the meantime, some county officials from Tonopah had heard of our school project. They came to the school and demanded to know why we took the old poles. When I told them that Scotty gave them to me they became furious and said that he was a damn liar, that he never owned them, and that they belonged to the County. They fumed around for awhile but told us to take no more. The equipment was used by the children for over twenty-five years, and we were richly rewarded for our efforts, as the poles had been standing unused in the desert for over a quarter of a century. Death Valley Scotty had made a great contribution to the Beatty children.... This episode with Scotty was quite a joke among the town folk and around the saloons for a long time. The admiration of Scotty for his gift to the school was long lasting (Moore, 1979:23-24).

Moore and Dees also laid out a basketball court and installed a hoop; all the children enjoyed the game-especially the Indians, who were good athletes (Moore, 1979:21).

Children at Play

Though the town of Beatty was small and lacked recreational facilities, the children never wanted for things to do. At school during recess the younger children used the facilities Moore and Dees had constructed; the older ones played basketball or baseball on a field that was nothing more than a patch of desert strewn with rocks and brush. May Day, the first day of May, was an important occasion at the Beatty school. Instruction was suspended and the day was devoted to a variety of athletic activities, including foot races, long-jump and high-jump contests, and ball games. The Indian children often dominated; sometimes, the Indian girls outperformed the Anglo boys.Boys derived great pleasure from playing marbles. A circle about 3 feet in diameter was scratched in the dirt and each player placed several marbles in the circle. The object of the game was to try to knock out the marbles that were inside the circle by "shooting" another marble from the outside. Holding a marble between thumb and index finger, the player used a flecking motion with the thumb to propel the "shooter" marble. The shooter marble, also known as a Tau, was a lad's most valuable marble. Players got to keep the marbles they knocked out of the circle. The families of Anglo boys in the community could often afford to buy their sons more marbles, which eventually ended up in possession of the poorer Indians, who were usually better players.

Another favorite activity of children in town was to roll their favorite old automobile tires. Children who had bikes often rode them to the hot springs located 5 miles north, though there was no pool there-the hot water emerged from a tunnel. Miners in town who lacked hot water in their cabins often used the springs for a Saturday night bath. Jack Crowell and a friend used to walk along the curb of Main Street of Beatty looking for discarded Bull Durham tobacco sacks, which they took home and filled with purple-colored fluorspar ore from the Crowell Mine for use in playing mining (J. Crowell, 1991). Girls played jacks and both girls and boys played a game called Red Rover. They would join hands and form two lines opposite each other; representatives from each line would alternately try to break through the other line. Games of hide-and-seek and kick-the-can were played by young people of Beatty even into their teens (J. Crowell, 1991). Sometimes a boy and girl who had hidden together might use the short time before their discovery to snuggle a bit.

For a time a movie was offered once a week in the old Town Hall. It was also considered great fun to go down to the railroad station and watch the arrival of the T&T.

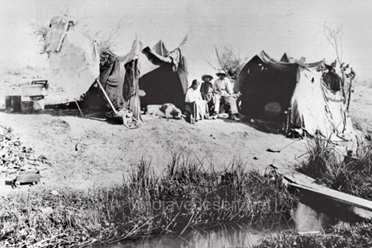

The Beatty Indians in the 1920s and 1930s

During the 1920s and 1930s, there was an Indian camp in Beatty located on the east side of the railroad tracks, sheltered in cottonwood trees along the river. The majority of the ap-proximately 15 families living there were Shoshone; they represented bands from throughout western Nevada and eastern California, including Death Valley, Lone Pine, and Bishop. Some came from as far away as Elko. Their homes were makeshift and had no plumbing. Water was carried in buckets from an outlet across the tracks belonging to the railroad (T. Cottonwood, 1987; Gillette, 1987).Prior to the Depression, many of the Indians worked for the railroads that served the area and some helped construct Scotty's Castle. In the 1930s it was reported that a high percentage were employed by the Works Progress Administration. When that program ended and the railroads folded, the community disbanded and members did not return. Indeed, the camp was usually deserted during the summer as families went their various ways to cooler areas. Some visited relatives; others would migrate to camps in the surrounding mountains (T. Cottonwood, 1987; Gillette, 1987).

For several weeks in the fall, beginning in late September, the Indians in the Beatty area were involved in harvesting pine nuts. During that time, the Beatty school would be virtually deserted of Indian children. The Indians camped at traditional spots in the mountains and picked pine nuts for as long as two months. The first pine nuts were roasted in the cone in a large, bowl-like structure made of dried brush. A ceremony was performed and the bowl set on fire. Pine nuts were stored in sacks for use later in the winter months (T. Cottonwood, 1987; Gillette, 1987).

Conclusion

Between 1920 and 1940, Beatty was the economic hub of a vast area stretching from Sarcobatus Flat in the north to Ash Meadows in the south and from Death Valley on the west to the Lincoln county line on the east. Although the town experienced little growth, residents were able to earn their living by working for the railroad, owning and working in local businesses and small mining operations, and being employed in local and state government. It was a friendly community-everyone knew and respected each other. Still very much isolated, in many ways Beatty remained a small frontier town-a frontier oasis. Except for the automobile, it was scarcely indistinguishable from many communities found in the American West fifty years earlier.To read more about Beatty after WWII click here for the full text by Robert d. McCracken.

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/legalcode

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/legalcode https://ia800501.us.archive.org/11/items/AHistoryOfBeatty/beatty2.pdf

BEATTY, NEVADA

by Robert D. McCracken

Nye County Press

Tonopah NEVADA

The Land and Early Inhabitants

Exploration and Settlement

The Boom Is On

Beatty Beginnings

The Late 1920s to World War II

Leadfield - Death Valley National Park

Tonopah, Nv.

Tonopah, Nv.

Skidoo - Death Valley National Park

Waterman, Ca.

Goldfield Stage

Beatty Museum

Bulllfrog/Rhyolite

Las Vegas, Nv. 1907

Railroad construction 1907 (UNLV)

Railroad construction 1907 (UNLV) S.P.L.A. & Salt Lake R.R. (UNLV)

S.P.L.A. & Salt Lake R.R. (UNLV)