Introduction

Physiography

Weather Data

Geologic History

Changing Climates

Weathering & Erosion

Carbonate Rocks

Granitic Rocks

Volcanic Rocks

Faults

Pediments

Stream Channels

Stream Terraces

The Mojave River

Playas

Sand Dunes

Human Impacts

References

Pediments and Alluvial Fans

The term, mountain front, is an imaginary borderline between a

mountainous area and a low, gently dipping plain (either a pediment or

alluvial fan). A

pediment

is a gently sloping erosion surface or

plain of low relief formed by running water in arid or semiarid region at

the base of a receding mountain front. A pediment is underlain by bedrock

that is typically covered by a thin, discontinuous veneer of soil and

alluvium derived from upland areas. Much of this alluvial material is in

transit across the surface, moving during episodic storm events or blown

by wind.

NPS photo

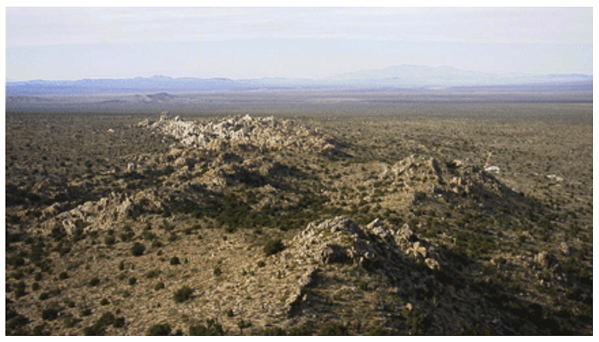

Granite exposures and rounded boulders shaped by spheroidal

weathering crop out on the pediment surface blanketed by a the high

Mojave desert mixed juniper and Joshua-tree forest in the vicinity

of Teutonia Mine along Cima Road.

Pediment-forming processes are much-debated, but it is clear that rocks

such as granite and coarse sandstone (and Tertiary conglomerate made up of

boulders of these rocks) form virtually all pediments in the Mojave

Desert. These rocks disintegrate grain-by-grain, rather than fracturing

and then being reduced in grain size by alluvial transport processes.

Alluvial fans

are aggrading deposits of alluvium deposited by a

stream issuing from a canyon onto a surface or valley floor. Once in the

valley, the stream is unconfined and can migrate back and forth,

depositing alluvial sediments across a broad area. View from above, an

individual deposit looks like an open fan with the apex being at the

valley mouth. Typically the fans formed by multiple canyons along a

mountain front join to form a continuous fan apron, termed a

piedmont or

bajada.

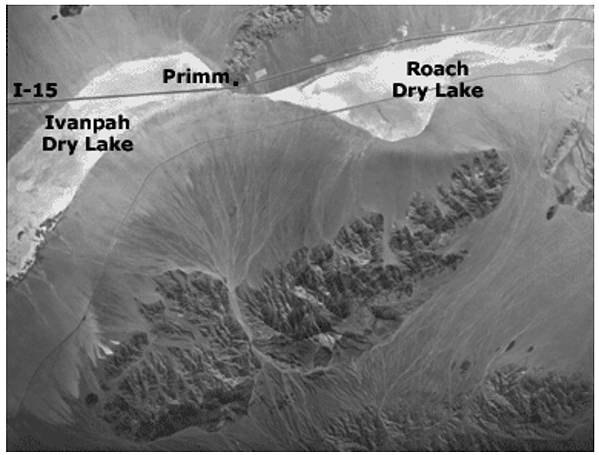

Lucy Gray Fan

Aerial view of Lucy Gray Fan, an alluvial fan that radiates from

a canyon cutting through the Lucy Gray Mountains and drains into the

Ivanpah Valley (north of the Mojave National Preserve in Nevada).

Below the mouth of the canyon the stream divides into several

channels. Active channels (void of vegetation) appear white,

whereas, darker areas on the fan are covered with vegetation and

possibly a thin veneer of soil. Channels migrate as they become

choked with sediment as flood waters seep into the ground. Coarser

rock fragments remain high on the fan, whereas finer materials

(sand, silt, and clay) will continue to migrate downslope. Only

during more intense storms will water reach and pond on the Ivanpah

playa.

Large areas within the Mojave Desert are pediment surfaces. These

pediments reflect both the antiquity of some mountain structures in the

region and the persistent arid climatic conditions in the region. Perhaps

the most notable pediment in the region is Cima Dome,

a very broad,

shield-shaped upland area within the Mojave National Preserve (below).

This great, gently-sloped upland area represent a region where

desert-style weathering and erosion has stripped away most of the relief

to the point that the erosion keeps pace with surface weathering and that

surface gradient is gentle enough to prevent gully-style downcutting.

Isolated rocky hills or knobs that rise abruptly from an erosional surface

in desert regions are called inselbergs.

NPS photo

The broad, gradual arch of Cima Dome is a mature pediment

surface broken by relatively small "rock islands" (inselbergs).

Teutonia Peak is the small peak to the left of the high point on

Cima Dome. This view is from along Cima Road, about five miles (8

kilometers) south of Interstate 15. The flat plain in the foreground

is also a pediment with a thin veneer of alluvium.

NPS photo

This view from the top of

Teutonia Peak

faces north over the

northern flank of

Cima Dome. Rock

knobs of spheroidal-weathering

granite bedrock rise above the pediment surface that consists of

barren weathered granite bedrock covered with a thin intermittent

veneer of sediment and soil. This expansive pediment surface

probably extends to the flank of the mountains in the distance.

(This is looking back toward the foreground area shown in the image

above.) Rock underlying Teutonia Peak is Jurassic grainite, which

generally does not form pediments; adjacent pediment-forming rock of

Cima Dome is Cretaceous in age.

NPS photo

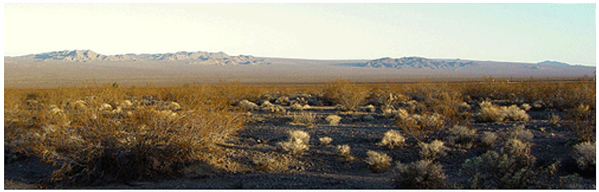

Pediment domes and islenbergs define the landscape in the

central portion of the Mojave National Preserve. This view faces

north from an alluvial fan draining the Providence Mountains towards

the pediment dome upland region of the Marl Mountains. Kelso Wash is

the axial trunk stream in the middle of the valley. In the

foreground, a relatively stable alluvial fan surface consists of

desert pavement broken by braided stream channels and a patchwork of

vegetation (mostly white bursage [gray] and creosote bush [green]).

Total surface relief in this lower portion of the fan is in the

range of one meter.

The development of pediments and alluvial fans is progressive with the

uplift of mountains and subsidence of adjacent basins. Pediments reflect a

relative "static equilibrium" between erosion of materials from upland

areas and deposition within an adjacent basin. The slope of the landscape

is gentle enough that weathering and transport of sediments from upland

areas and the pediment that no significant stream incision occurs. In many

areas throughout the Mojave region it is nearly impossible to see where a

pediment ends and alluvial fans begin, however, geophysical data and

water-well drilling shows that in many places sediment filled basins do

occur adjacent to pediment areas.

The impact of climate change on alluvial fans has been the focus of

much research. Studies show that a period of elevated alluvial fan

deposition occurred between the time of the Last Glacial Maximum (about

15,000 years ago) and the beginning of arid conditions in the early

Holocene (about 9,400 years ago). McDonald et al, (2003) suggest

that the climatic transition from seasonable wet conditions to arid

conditions, punctuated by extreme storm event (possibly associated with

tropical cyclones) may be responsible for this change. Today, heavy

rainfalls rarely provide enough precipitation to allow enough surface

runoff to occur on highly porous soils and colluvium. Only during major

stream event will water discharge in volume and intensity to move material

from mountain source areas to lower fan areas. In addition to extreme

storm events,the buildup of alluvial fan deposits at this

Pleistocene/Holocene time transition may be linked with the transition

from widespread plant cover to the more barren character of the modern

Mojave landscape. Die-back of plants would decrease rooting, making more

mountain-side material available for erosion and transport to alluvial

fans.

Next > Stream Channel Development