Native American History in the Mojave Preserve

Native Americans and Anglo Contact

About 11,000 years ago, the region's ecological zones were one thousand feet lower in elevation than today due to the cooler

and wetter weather patterns of the waning Ice Age.

Streams flowed and lakes existed

where

dry playas

are today. The relative

abundance of plant communities supported

wildlife

and

indigenous peoples

who depended upon the natural resources. While clear

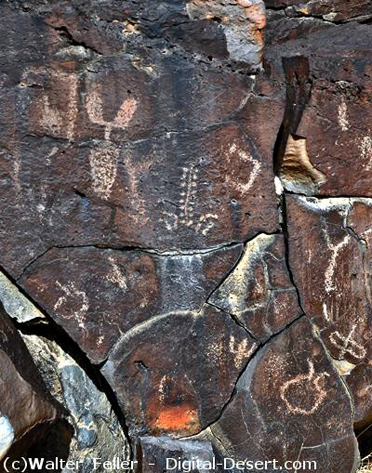

archaeological evidence of human presence in this early time are sparse, over 1,300 later prehistoric and historic period

archaeological resources have been recorded for the large Preserve area, including 65 rock image sites. Museums and professional

researchers have made significant collections of artifacts since 1925.

In general, these tribal peoples occupied the lands as small, mobile social units of related families who traveled in regular

patterns and established summer or winter camps in customary places where water and food resources were available. Archaeologists

named

a series of five manifestations of Native American occupation,

which were believed to describe changes in climate, chipped

stone technology, and subsistence practices of these early peoples. These periods covered time intervals from about 5000 BC to

AD 700-900. At that point, the Mojave desert area, unlike other portions of California's desert region, was influenced by native

peoples now called 'Ancestral Pueblo' who established farming villages along the

Muddy,

Virgin,

and

upper Colorado

rivers. Their

culture reached into today's Preserve lands at turquoise sources and via trade trails as far as the Pacific coasts. Later, however,

Ancestral Pueblo peoples abandoned their territory and were replaced by

Shoshonean

and

Paiute

peoples after about AD 1000. In

addition, native peoples of the

lower Colorado River

basin speaking Yuman languages expanded their river zone territory and utilized

some desert lands as well.

Modern Native American "tribes" were products of interactions with the

American military

and legal system as much as modern

reflections of pre-contact Native American land use patterns, and the land allocated to these groups frequently did not reflect

the actual extent of their pre-Anglo homelands. No tribes directly control any lands in the Preserve, but historical, archaeological,

and ethnographic information indicates that ancestors of the modern

Chemehuevi

and

Mohave

Tribes traveled, camped, hunted, and

resided at various places now in the Preserve. Oral traditions and historical information compiled into maps for the 1950-1960s Federal

Indian Lands Claims cases showed Chemehuevi land knowledge and uses. Some Mohave Tribal members have family histories of being on

lands now within the eastern areas of the Preserve. Certainly, the very detailed and lengthy "song cycles" of the Chemehuevi identify

many places within the Preserve with names and events of supernaturals who performed various activities there. The "song cycles" were

a type of oral map of the territory which had great value to travelers moving through the area or following seasonal foraging patterns.

However, both tribal groups sustained hostilities between themselves, which was noted by Spanish

Friar Francisco GarcÚs

in 1776.

Euro-American contact with peoples now called Chemehuevi or Mohave increased in the nineteenth century. [1]

The Desert Chemehuevi were Native Americans who actually lived most of the year in the area of the Preserve. Limited food and water

resources sustained a low Desert Chemehuevi population density. When food was abundant, it would be dried and cached for later use. The

area of the Preserve probably never supported more than about 150 people at any one time. [2]

While the Chemehuevi were the primary inhabitants of the area now encompassed by the Preserve, the desert and the park itself are named

for a different group of Native Americans - the Mohave. [3] The Mohave were agriculturalists who planted in the flooded plain of

the Colorado River. This agricultural lifestyle generated food surpluses, which enabled them to support a sizable population in the

river basin area, numbering in the thousands. The Mohave frequently traded with other Native American groups to the west and east, and

had a particular fondness for seashells traded by Indians on the California coast. The Mohave had a network of trails across the desert

from waterhole to

waterhole. The

Mohave bragged to early European visitors that a powerful Mohave runner could make the trip to the Pacific

coast, more than 150 miles long, in three days. The Mohave guided some of the first non-Indian travelers over this network of

trails, including friar GarcÚs in 1776 and American trapper

Jedediah Smith

in 1826. Their network of trails, now known as the Mojave

Road, became one of the main routes used by the government and other travelers to cross the desert before the advent of the

railroad.

The Mohave were friendly to GarcÚs and Smith at first, but when Smith returned to recross the river in 1827, the Mohaves attacked as his

party was crossing. Historians later determined that other trappers, arriving between Smith's two visits, killed several Mohaves and

antagonized the rest, prompting the tribe to exact revenge on the next Euro-Americans they saw. Half of Smith's party was killed, and

the explorer led the survivors back across the desert trails to relative safety in California. This incident created the reputation of

the Mohaves as a fierce band that should be avoided. [4] Further encounters with trappers in the late 1820s and early 1830s led to more

bloodshed by Indian and Anglo alike. Historians hypothesize that the

Old Spanish Trail,

which runs to the north of the Preserve, was

created in the 1830s specifically to bypass the Mohave. [5]

In 1848, the United States signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo to end the Mexican War and received almost all of the territory that

is now the American Southwest, including all of California and all of the area of the Mojave National Preserve. Interest in building

a transcontinental railroad was high, but the choice of route was difficult due to sectional controversies. In 1853-54, the United States

sent several survey teams into the field to report on the feasibility of the various routes. One of these was the so-called

35th Parallel Route,

which cut through the eastern Mojave. Two survey parties took the field: one, under Lt. Robert S. Williamson, explored from the western

side and proceeded as far as

Soda Lake;

the other, under

Lt. A.W. Whipple,

proceeded from Arkansas to Los Angeles, crossing the Preserve

along the route of the

Mojave Road. [6]

Later attempts proved more successful at opening the cross-desert route now known as the Mojave Road. Between 1855 and 1857, the General

Land Office surveyed township lines throughout the area. This effort was largely wasted when the location monuments could not be

rediscovered by others, but the small number of people on the surveying teams became very familiar with the desert and later served as

guides for other expeditions. In 1857,

Edward F. Beale

surveyed a wagon road across the Arizona desert, and crossed the Mojave along

the route of the future Mojave Road. Combined with his eastbound crossing in 1858, Beale's success proved the viability of the wagon road.

1 Lorraine M. Sherer and Frances Stillman, Bitterness Road: The Mojave, 1604-1860 (Needles, CA: Mohave Tribe / Ballena Press, 1994). I am indebted to Roger Kelly, Senior Archeologist, NPS Oakland, for much of the information and wording in the preceding paragraphs. Comments by Roger Kelly on first draft, June 25, 2002. For information about Chemehuevi songs, consult Carobeth Laird, The Chemehuevi (Banning, CA: Malki Museum Press, 1976), 9-19.

2 Chester King and Dennis G. Casebier, with Matthew C. Hall and Carol Rector, Background to Historic and Prehistoric Resources of the East Mojave Desert Region (Riverside, CA: Bureau of Land Management, California Desert District, 1981), 20.

3 Generally, the tribe and places named after the tribe in Arizona are spelled "Mohave," the fort in Arizona, the desert, and other places in California are spelled "Mojave." See Dennis Casebier, The Mojave Road, Tales of the Mojave Road #5 (Norco, CA: Tales of the Mojave Road Publishing Co, 1975), 182n1.

4 This incident was likely precipitated by violence toward the Mojave by an earlier trapping party, under the command of Ewing Young. Later trappers, such as Peter Skene Ogden, also massacred Mohaves without warning, contributing to the tension. Casebier, Mojave Road, 24-28.

5 Casebier, Mojave Road, 30-31.

6 Casebier, Mojave Road, 57-66.

Source - NPS:

From Neglected Space To Protected Place:

An Administrative History of Mojave National Preserve

by Eric Charles Nystrom

March 2003

https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/moja/adhi2.htm

Petroglyphs