The Town

THESE DRAWBACKS must have dismayed the faithful. For by early March, the country had become "alive with prospectors, who go out on the desert wastes and sand plains to prospect, with buggies and buck boards and two-horse wagons to haul grub and water. . . ." Fifty to 100 persons lived in town. E. Sommers, in the meantime, was shipping in lumber, five tons of machinery, and a smokestack to build a five-stamp mill. The miners would "hail with joy the speedy completion of the mill."

The business district was worthy of a new town. Fifteen buildings lined the main street in late April; they included three saloons, two stores, two eating and lodging houses, and a hay yard. With eight families present, lumber was ready for the construction of a school and butcher shop. A post office, at long last, was established in late May, though a building apparently was not ready for service right away. Then, in June, a printing plant was reported on its way from Los Angeles to publish a paper "under the euphonious name of Calico Print." A stage now began making 62-hour direct trips from Los Angeles; the fare was $10. One writer observed 18 "heavily laden" teams bound for the town on a single day. As summer began, Calico embraced 20 buildings and many tents; at Fish Ponds Station, two partners were making adobe bricks, for mud houses at Calico "will make cool and pleasant resorts. . . ." A hotel was now rising, and a saloon and another hotel were planned.

The boom showed two faces: the rawness of a mining camp, the vigor of a mining district. The genteel Mrs. Harwood, for example, called the district one of the most "cheerless, desolate, uninviting" places she had seen. The area was crowded with about a dozen women and 300 men, many of whom slept in tents, a few under the stars, and others under overhanging rocks- -anything to shelter themselves from the furious winds arid scorching sun. Yet only 70 men worked in the mines, and 30 others worked their own claims.

Calico resembled Tombstone, Arizona, or Bodie, California, to suit her. ". . . . Nights and Sundays the streets are thronged with men, who are of all grades of intelligence, and all qualities of character; some in point of decency being below the brutes. They run riot in their lusts, and already some of the most disgraceful and audacious proceedings have shocked the sensibilities of respectable men and women. . . . "

True enough. But Calico had come a long way since the previous July (1881), as the Print pointed out: ". . . . If one year has made so decided a change, what may we not expect during the next 12 months? From present appearances we hazard the opinion that ere another year shall have rolled around our little wooden village will have given place to an active, but bustling mining town, second to none in this or any other State or Territory. Surely the richness and number of mines demand it."

The Print was a bit premature. Summer brought intense heat, as usual, and an epidemic. The founders of the newspapers refused to leave. And by early September, the disease had run its course, the weather was pleasant, and travel was again increasing, for "it is likely that for some months to come there will be a tremendous tide setting this way. . . ." E.E. Vincent one of the Print's founders, fanned the boom when he showed a Los Angeles editor specimens "so rich in silver and so free from grit or other substances that they can be whittled with a knife without damaging the edge. . . . (The editor was referring to silver chloride, or "hornsilver," which has the consistency of hard cheese.) Again the mines were in operation; again the town was "alive with business." When young Herman Mellen, then 15, arrived with his father in late September to build mine works, Calico, half buildings, half tents, made "quite a showing." In a restaurant, the talk "sounded as if at least half the diners were wealthy men to whom a few thousands of dollars were a mere bagatelle. While we ate, mills and roads were planned, railroads laid out and new camps started as though such things were mere incidents of the day's work. . . ."

The town still remained fairly small, with perhaps 300 residents. Yet it supported a flourishing business district. Among the businesses in October were three hotels, a new post office (part of a store), the newspaper, at least four grocery and general stores, a liquor-cigar store, a meat market, a saloon or two, three restaurants or boardinghouses, a wood and water dealership, besides a lawyer, notary, shoemaker, barber.

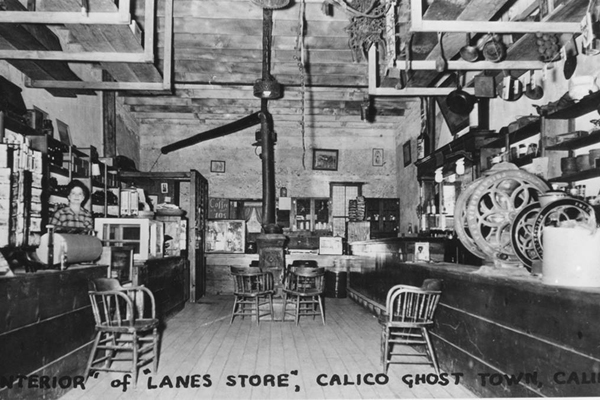

Interior of Lane's store

A reporter for the Print was proud of what he saw. Lining Main Street (October) were three hotels and seven cottages or other comfortable homes; the occupants ran assaying offices out of their houses. Near the lower end of the street stood the Calico Hotel and a restaurant called The Three Graces--it was more like a boardinghouse--which was run by three women, including the wife of merchant Joseph M. Miller. The trio also sold bread and pies. Farther up was the notorious Hyena House. The Hyena House was no ordinary hostelry. It was built in the hollow of a large rock. The outside was cased with barrel staves, and its rooms were holes the rock. It flew an American flag "and harbors untamable patriots, including the unterrified Dick Hooper, who was never defeated in an argument, from the discussion of the Darwinian theory to that of the late Ohio election. . . ." Near the head of Main Street stood the Pioneer Hotel, the first in Calico. It was said to have the best location and offer the best accommodations.

A wide variety of retailers advertised goods and services. The Pioneer Grocery Store, in the post office building, offered groceries, miners' supplies, and medicine. E.J. Miller's Pioneer Market sold fresh beef, hams, and bacon. J.M. Miller, who received weekly shipments from San Francisco, offered fine wines, liquors, and cigars, besides fresh Milwaukee beer. Alfred James, another merchant, sold Kern River flour and Hercules giant powder (dynamite), which he stored in a powder magazine build "at considerable expense." Adjoining the James store was the tent store of the J.A. Kincaid & Company. The rear of the tent, 22x44 feet, was occupied by the manager's family; the front was filled with shelves and counters holding the usual groceries and mining supplies. No wonder young Mellen considered the prices for food reasonable. G.D. Blasdel, a capitalist and friend of the Mellens, ran the Globe Chop House, where John Doyle kept his barber chair. Michael Redman repaired boots and shoes.

But water was expensive, about five to 10 cents a gallon. Evans & Phelps supplied "fresh water at reduced prices" from wells two miles east of town, near the dry lake. Even with careful use, Mellen recalled, one person could use one dollar's worth in a day or two.

Calico was civilizing rapidly when the Mellens arrived. The Reverend Charles Shilling conducted the first Christian service in late October at the James store. The audience, numbering 15 to 20 men, five women, and several children, listened attentively to the "eloquent divine," who saw the meeting as the start of "a new era in the history of Calico." More down to earth, politics occupied the attention of many, Postmaster W.L.G. Soule was running for justice of the peace; John Overshiner, publisher of the Print, was running for constable. (He lost.)

Education also occupied Overshiner's attention. When 20 children were found to be living in town (October), the paper demanded a school. After a census found 93 children of school age, probably in early 1883, the county supervisors established the Calico School District. Instruction began for 58 pupils in a small building lacking furniture, at least at first. Still, it was a start. Overshiner later served on the school board.

Calico in fact could be a fairly homey, family-oriented community. When Christmas of 1882 approached, a young store clerk asked a friend of the Mellens to cook a large turkey his parents would be sending him. She could invite as many friends as she wished. But the turkey spent a week in transit and the weather was warm. Not wanting to hurt the youth's feelings, she commandeered all the canned turkey off the shelves of her husband's store. The turkey was delicious. Nobody, certainly not the youth, wondered how one bird could have 12 drumsticks. But the season only brought misery to Herman Mellen. The winter and spring of 1883 were unusually cold and cruel. Flu swept the camp; drugs ran out; many residents died. His lungs nearly useless, Mellen coughed and strangled for endless days. To the rescue came Mrs. Annie Kline Townsend (Mellen mistakenly remembered her as Mrs. Belle Murdock), a woman prospector and mine owner whose cabin stood next to their tent. She sent over a cough syrup made of salt, vinegar, butter, onion juice, and honey. It worked like a charm. It was so potent that a misdirected squirt of it once etched the barrel of a shotgun owned by the elder Mellen.

Except for this new epidemic, Calico was "fairly started on the road to prosperity," declared the Colton Semi-Tropic at the start of 1883. Mining was increasing, roads were under construction, a mill--the Oriental--was almost ready to run, a railroad had just been completed near the Mojave River and a depot erected, buildings had been enlarged and others were planned, stores were getting stock, travel was increasing, the hotels and lodging houses were "doing a good business; and in short, all the various business enterprises in this vicinity are gradually growing in importance, and we may safely predict that before many months the mining operation here will be extensive, and will support a large and flourishing town."

Indeed, the frontier days were getting to be a thing of the past: government was well represented on several levels. The Calico area was a mining district, school district, voting precinct, and a court township. As a court township, Calico was entitled to elect at least one justice of the peace and constable. Among government officials' were the constable and justice of the peace, who could double as coroner's deputy or school-census marshal, perhaps a deputy sheriff, election workers, a mining district recorder and deputy, a postmaster, a deputy U.S. mineral surveyor, school-board members, and a teacher or two. The chief officials in a camp tended to be the postmaster, justice of the peace, constable, and secretary (administrator) of the school board.

Oro Grande and Waterman

Discovery of the Calico Mines

The Camp

The Town

Roads & Rails

Rugged Individualists

The Calico Print

Bismarck Camp

Mines & Mills

Town Life

The Decline

Daggett

Calico: Rally & Collapse

Calico Gothic - The Lanes