Town Life

Albert Barber Home, Calico 1885 - courtesy Orange County Archives

CALICO PROBABLY CAME OF AGE during 1884. Reminiscences and scattered issues of the Print and other publications reveal a rich social and business life.

CONSIDER CALICO'S POLITICS. The camp gained outside recognition during the campaign of late 1884. Grover Cleveland was running against James G. Blaine for the presidency. On the regional front, R.F. Del Valle, a Democrat, was running for Congress against Republican H.H. Markham, an official of the Oro Grande Company.

The issue in California was appropriate for a mining state. For years, hydraulic mining in the Sierra Nevada was pouring silt into the Sacramento Valley and ruining prime farmland. In the courts, the farming interests were waging a successful battle to severely restrict the mining operations. Del Valle sided with the farmers, Markham with the miners.

Del Valle arrived first--alone--in late October. His was the first appearance made by any major candidate in camp and was its biggest event. A brass band had just been organized, and the Democrats had spent 10 days in preparation, stringing Chinese lanterns over Main Street and attaching torches to buildings.

Del Valle's appearance turned out to be a strange rally. The "excellent music" provided by the band consisted of only part of one lively tune repeated several times--its entire repertoire. And chairman Levi (Pa) Pennington, a restaurant owner and encyclopedia of Democratic Party history, was repeatedly interrupted by wags--Republicans?-- demanding to know about some remote political event. Happily, Del Valle was too seasoned a candidate to allow this routine to continue. He finally interrupted Pennington and asked him to explain some obscure point. Pennington was only too happy to deliver another lecture. The result was that Pennington spoke for more than an hour and Del Valle spoke about 20 minutes, most of the time complimenting Pennington and praising his knowledge of party lore. Del Valle no doubt gained many friends and votes. But Markham, who arrived a few days later, enjoyed a greater advantage. He favored hydraulic mining and spoke in a mining community. He also arrived with a considerable entourage, including all the Republican candidates in San Bernardino County. It also helped that most of the region's newspapers, including the Print, were stalwart Republicans. Markham was hailed as a hero, according to a correspondent for the Los Angeles Times.

Markham spoke from a "tastefully decorated" platform to an audience of 500, made up of miners, their women friends, and visitors from San Bernardino. ". . . Torches and lanterns made the near vicinity of the platform one blaze of light. A brass band and fine glee club made enlivening music. . . ." The audience "listened patiently for three hours to Republican claims and logic. The cheers and applause throughout the various speeches forces one to think that Democracy never was so solid here as it's supporters claimed. One thing is certain--Democracy has been running a campaign of lies and misrepresentation in Calico. . . ."

Markham won easily, but Cleveland was elected president. CA few months later, the Democratic Club gave a ball to mark Cleveland's inauguration. The Republican Print conceded that there "was a large attendance and everybody had a royal good time.") .

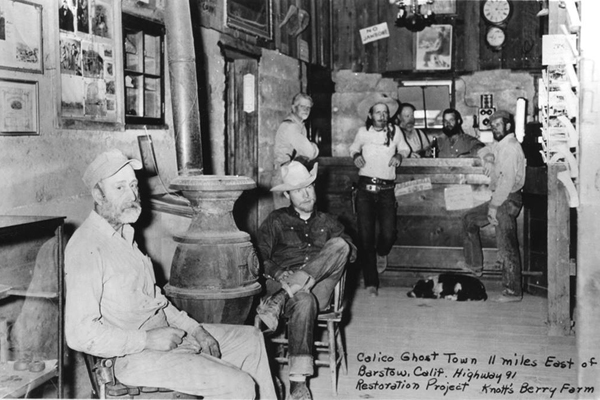

Other visitors of note were making the town itself known to the world. When Frederick W. Smith, an agent for the Mining & Scientific Press, traveled along the single "narrow and serpentine street" in late February, 1885, he was at once amazed and appalled. Smith was not the first--nor would he be the last--to remark upon the two-sided nature of the camp. ". . . Small, hastily-built houses are the order of buildings, only a few two-story houses gracing the camp. Saloons are more than numerous. Business generally is overdone, and the number of black-legs and tin- horn gamblers that infest the place is remarked by the newcomer. . . . The Occidental and Whitfield House are the only hotels, and they are pushed to their utmost capacity to accommodate the travel that is arriving daily. The camp is a good one, but at present is overestimated and overcrowded by men out of money and work. Capital, development and a chance is all that this camp needs to be a second edition to the Comstock at no great distant date."

Happily, the cost of living remained moderate. Cold beer cost five cents a glass; water cost three to five cents a gallon. Wood sold for $10 a cord. Board cost $7 to $8 a week. As Smith noted, business was indeed overdone.

There was, for example, no shortage of saloons. In Daggett, Quinn and Sutcliffe were building a two-story, 12x16-foot addition to their brewery in February, for "their business has been better 1during the winter than they had anticipated and they are preparing for the expected boom in the summer." In Calico, Stocking and Martin were "doing a paving business retailing liquor to the miners, and many a demijohn is filled with the ardent daily. Their liquor, 100 proof, is sold direct from the barrel and is warranted as represented." Only weeks later, the partners were "meeting with success in their retail liquor business beyond their most sanguine anticipations. They did not expect in such a short time that their sample rooms would be the scene of so much animation as the crowds of miners file in and out, showing by their countenances the satisfaction they feel [by] partaking of liquors that are unexcelled in the local market. . . ." During February, their saloon had taken in $1,490, or $53 a day.

And so it went. Other saloons opened or expanded or reported good business. Kirwin and Flynn in March enlarged their saloon again, adding 40 feet to the front. ". . . They spare no pains to make their hall attractive, and furnish of evening free music with organ, violin and other instruments."

The hotels were also "all doing a lively business. The Occidental has been full to overflowing since the day it opened. . . . and its table filled with day boarders besides. . . ." The Whitfield House went in for elegance. The doors were "grained," gemstones were painted on the baseboards, and wallpaper and paint laid on. A verandah extended from the second story, the furnishings were "excellent in every way," and the rooms were considered "bright and cheerful"--each even had a rope and- anchor fire escape. (Not to be outdone, the Occidental soon added a verandah, too. The camp's three general stores fared almost as well as the hotels and saloons. J.A. Johnson bought the James brothers' store in March and moved in merchandise and post office fixtures, for which a room had been prepared. The J.M. Miller store was enlarged by 20 feet, and merchandise would be moved in from its warehouse. Though it would be taken over by creditors, Remi Olivier's J.A. Kincaid &. Company had been expanded until it was now 75 feet long; it was "packed with goods from one end to the other."

.jpg)

Drug Store

Calico also supported a rich array of smaller businesses. A Mrs. Elliott furnished ice cream for picnics, balls, and other entertainments. Tailor A.S. Mettler made "suits that fit, at prices to suit the times." At the Globe Restaurant, Mrs. M. F. Oswald cooked meals at all hours for 100 boarders a day. Mill superintendent Godfrey Bahten and stage operator William Curry owned butcher shops in Daggett, Grapevine, and Calico. During late winter and spring of 1885, Curry slaughtered 279 head of cattle, 140 sheep, and 80 hogs, all valued at about $10,000. Soule and Stacy, who once kept the post office, sold watches, clocks, jewelry, and sewing machines. Two saloon owners built a large bathhouse for men and women. At least three lawyers and four doctors practiced in Calico. Though nearly deaf, old Dr. A.R. Rhea turned out to be the mainstay of the camp's medical profession, delivering most of its babies and aiding the victims of mine accidents. One doctor also owned a drugstore.

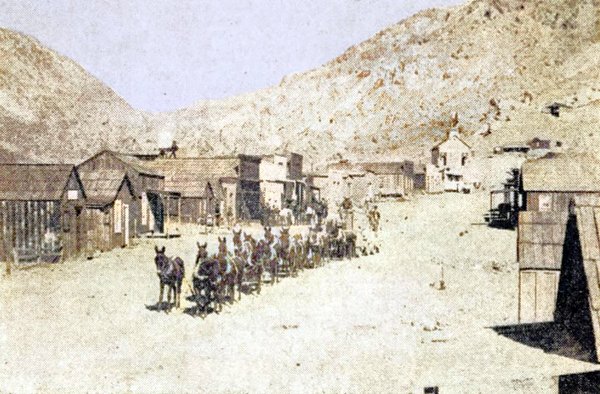

Itinerant businessmen supplemented the offerings of Main Street. A photographer set up a large tent in March taking pictures of the town, school, mule teams, and mines. Repairs to the teeth were provided by a dentist from Santa Ana.

DAGGETT, MEANWHILE, was flourishing. School districts were organized there and in Needles that spring (1885). Overshiner served as one of the three trustees. Daggett's residents and business owners took great pains to enlarge, remodel, and paint their buildings. Perhaps because Daggett was near the Mojave River, trees had been--or were being--planted in front of the railroad hotel, a saloon, a restaurant, a store, and several houses. Near the Quinn & Sutcliffe brewery awnings and trees were added so that the place "will be a pleasant place to sit on a summer eve's and quaff the foaming beverage. . . ." Freighter Joseph LeCvr, who was also deputy sheriff, refurbished his home, built a picket fence around the yard, and planted trees and shrubs. As soon as Daggett's trees "grow to considerable size and the gardens are in a more flourishing condition the town will look like a verdant garden," the Print predicted.

THE ENVIRONMENT invited some modification. The Print believed that trees could grow in Calico; the young cottonwoods in front of a merchant's house were "flourishing and bid fair to become splendid sunshades." The temperature hit 104 degrees in late May. The Print quipped in July: "As an example of how hot it is in and around Calico we will relate the fact that two lizards were recently seen on the desert in the act of standing on their hind legs making a shade for the other to cool off under. First one would stand up and then the other, spelling each other. Next!" (Still, the arid climate had its advantages, as the paper remarked that spring. Though Calico "has hots and colds, her fever and pneumonias, her snakes and tarantulas and centipedes, and no end to ills that mining camps are heir to, she enjoys perfect immunity" from bedbugs, at least.)

CALICO DEVELOPED some institutions to make life more palatable, if not quite comfortable.

After another epidemic in the winter of 1884-1885, a sanitary commission was organized. It apparently proved to be ineffective. As late as May, 1885, the camp remained "positively filthy in some quarters and the accumulation of nastiness is on the increase. Only a few days ago we observed a dead turkey sweltering in the sun, but we knew he was there before we came within sight of -him, for the breeze told our nose about it--fumigate, fumigate."

Self-government proved even less popular. In February, 1885, the citizens "sat down rather incontinently" on a proposal to incorporate Calico. The property owners and taxpayers seemed to feel that cityhood would "prove too expensive a luxury to offset the advantages of local government."

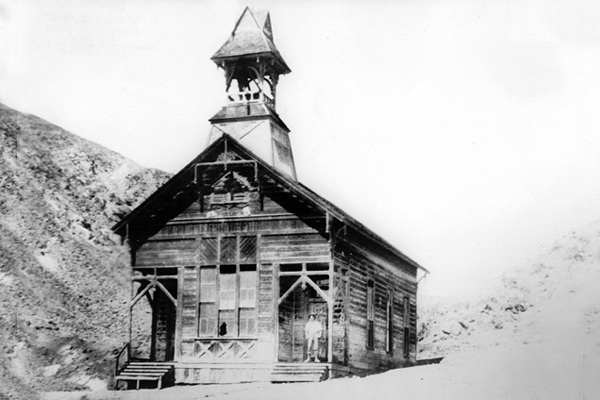

Calico schoolhouse

It was not that Calico's citizens were apathetic about political life. They enthusiastically supported all variety of candidates, maintained a school district, and certainly turned out to vote. During an election for mining recorder, 396 votes were polled for three candidates. But except for the school, the camp's citizens preferred to let a few private organizations and the county provide basic services. In March, the board of supervisors declared the district's chief roads, including Main Street, public routes. A county road supervisor at once began removing rocks and brush and widening Main Street and the road to Evans Well. ". . . By a little care on the part of the citizens the streets can always have a tidy appearance," the Print pointed out. The roads were indeed heavily used. Two stage lines made daily trips from Daggett. H.E. Evans, the water dealer, began selling coal. (A phone line ran from Daggett to Calico, but its use was apparently limited to the Oro Grande Company.)

Water service would remain in private hands. Several merchants organized the Calico Water Works Company in March, 1885, and soon began sinking a well. Good water was reached at 92 feet; a pump and 60,000-gallon tank were later installed.

POSTMASTER E.E. STACY, one of the organizers of the water company, was responsible for a less orthodox form of delivery. One morning in 1883, Stacy found a stray black-and-white shepherd at his doorstep. Stacy adopted him and named him Jack (one account gives the dog's name as Dorsey). The postmaster soon found that Jack would willingly and reliably carry mail in a saddlebag-like pouch on his back and put him on a regular, two-or three-mile route to the Bismarck mines, where Stacy had a partner. At 9 every morning, Jack would leave Bismarck with mail and take it to Calico, where the pouch was removed. Until 4:30 in the afternoon, "Jack is a dog like all other dogs, romping and playing with his fellow dogs, and taking part with them in their amusements. . . ." But when the mail bag was put back on, "the dog disappears, and in his stead stands a being of superior intelligence' who knows his duty and delights in the correct performance of it. . . . when little curs run out and offer to fight him he only laughs. Jack's daily routine teaches a greater moral lesson than all the sages between here and Halifax."

OVERSHINER needn't have worried. Calico was a civilized camp.

ONE OF THE INFLUENCES was religion. Calico never had a church, but services were held often. Many Catholics lived around Calico. Lectures given by the Reverend Father Cook in early 1885 "were listened to with marked attention. The erudite priest seemed to satisfy the audience. . . ." Weeks later, a large congregation heard the Reverend Charles Shelling of Riverside, who "preached an interesting and practical sermon." One clergyman, the Reverend D. McCunn, was so active in cultural affairs that when he preached his farewell sermon in July, his "friends bade him farewell with many expressions of God speed and wishes. . . ."

Except perhaps for the Print itself, the Calico school probably had the broadest influence on the town's moral life. Perhaps because of the district's isolation, teachers were hard to keep. Teacher A.L. Hamilton, who stayed only four months, reported 65 pupils enrolled in March, 1885, and 65 other children in camp. Perhaps not surprisingly, citizens voted a $3,000 bond issue in April to build a larger school and ordered a library of 60 volumes; several books had already arrived, and the board was expected to let the public use the library under rules it would adopt. The Print felt that the school trustees deserved "great credit for the efficient manner in which they conducted the election and for their excellent report on the subject. . . Calico will soon have a splendid building in which 'To rear the tender thought and teach the young how to shoot.'" When the school term ended in early June, about 46 children had regularly attended--an excellent record for a mining camp. .

14-mule team

Calico was no haven for weather-beaten bachelor miners: youths made up a large part of the population. And the Print doted on them and their activities. The paper was horrified to report that the constable's six-year-old son had been nearly crushed to death when a mule knocked him under a large ore wagon. Happily, such painful incidents were rare. When a man saw two teen- ager's planting stakes and stretching old pieces of wire around a section of trail, one of them told him that they were fencing in a lot. But, the gentleman objected, the boys were too young to hold real estate. "You bet we can. If anybody tries to jump my lot, I'll shoot him, sure pop." The Print grew misty eyed when it learned that young Brunett Lamountain was building a miniature stamp mill "that works perfectly as the Oro Grande or any others . . . . Such precociousness should be encouraged and assisted." A few weeks later came the report that the "miniature quartz mill erected and run by the Juvenile Company of Lamountain and Co., running nicely. Two additional stamps have been set up and a larger boiler placed in position."

A TOWN HALL nurtured family life. Spending about $760, the women had the hall built in early 1885. By renting the building out for lectures, dances, and entertainments, the treasurer reported in April, the town hall association would soon be free of debt.

The town hall was well used, sometimes once or twice a week. Several leading citizens, including old Dr. Rhea, organized a literary and debating society in February. The group usually met every Friday evening. Since the Print considered such an organization "a benefit to any community, it is hoped that the people will give attendance and help to sustain it. The ladies are especially invited to attend and to take part in the exercises." The society debated such topics as the value of a college education and the right of Indians to vote. The society soon attracted 20 members and created a committee to organize the festivities for July 4.

But in general, the hall was devoted to entertainment. The town hall association gave a musical and literary entertainment in March to raise money for the hall. For 50 cents (25 cents for children), members of the audience could enjoy 16 performances one night, including an Italian hymn sung by a choir, duets, readings, recitations, songs, and pantomime. A dance capped off the evening. Except for uncouth noises made by boys in the rear, the program turned out to be a resounding success.

Calico's citizens knew how to enjoy themselves. The women gave a "bowie knife" entertainment in June. A few weeks later, a traveling soloist, girl dancer, and impersonator performed.

But dancing was the chief pastime, as the Print explained in May, 1885: "When Calico wants to dance she doesn't go to any great fuss about sending bell ringers and town criers to announce the fact. She simply hires the music, plants herself in the Town Hall and awaits coming developments. Developments soon make their appearance in the shape of broadcloth, diagonal, etc. Developments seem to like it as well as Calico." That same week, the employees of the Silver Odessa Mine gave a ball in the dining room of the boardinghouse. From town, "merriment seekers" arrived in barouches, chariots, gigs, rockaways, buggies, and other carriages, danced until 3 o'clock Friday morning, "and everybody had a good time."

Daggett was equally festive. It even supported a glee club. Calico's residents would flock to Daggett like flies to food. At a lavish ball held at the railroad hotel, the dinner featured half a dozen large frosted fruitcakes and other pastry. The dance, as usual, lasted until the early morning, "and everything passed off smoothly and happily . . . ."

Next to Christmas, July 4 was the most festive day of the year. Daggett's residents held a picnic party at Hawley's Station, which offered sports, a dancing pavilion, beautiful shade trees along the Mojave River, and green fields, "where all the denizens of the sun burned hills of Calico, and its surroundings can find perfect enjoyment in a day's recreation in the country." At Calico, the women of the literary society put on a celebration that would "eclipse any previous demonstrations on that day." Calico's celebration included the customary oration, the reading of the Declaration of Independence and poetry, and music, dancing, games, exercises, and refreshments "so that the occasion will be a most interesting gala day when everybody can have a good time."

The July 4 celebration still failed to satisfy men and women living in a bleak environment. "Now that the 4th of July is a thing of the past, what are we to do next to amuse ourselves? We would suggest a moonlight picnic, instead of having one in day time: sweltering under the hot rays of old Sol."

ENTERTAINMENT COULD BE quite physical. At a literary society meeting, amateur athletes jumped during the evening. Meanwhile, in May, the "base ball has come forth from its hiding place, and is pitched and tossed promiscuously by the base ball artists."

Calico was especially excited by a boxing match in March. Several hundred persons paid $1 or more to watch a "glove contest, to a finish" between Dan Connors of Boston and Frank Smith of Chicago. After skirmishing during round 1, they finally started throwing "some very lively give and take blows." Smith closed in and threw Connors. But Connors was better trained. During the third round, it became clear that Connors would exhaust Smith, who "came up rather low" during round 7. Connors then gave Smith "a stunning blow on the muscle of the left arm," rendering it useless. Connors hit Smith on the jaw, knocking him down and out in 10 minutes. Connors won the gate receipts of about $268, but to show his good feeling toward his foe, he gave him $25 in cash.

CALICO HAD ITS ROMANTIC SIDE, TOO. As the days became warmer, a party of picnickers left for Hawley's Station, where a "moonlight dance will be, no doubt, as enjoyable as it is romantic. . . ." Meanwhile, that May, several men and women visited a cave near the Oriental Mine and "spread a choice collection of edibles beneath the roof of what once probably is an ancient mine. Some of the male picnicers say that a trip around the hills and a 'romantic dinner. . . . is the best kind of amusement and recreation."

The Print was not above making light of the romantic scene. "Time, midnight; scene, Wall Street; man and woman softly stealing up the street. Man in stockings closely following behind in the shadow of the abrupt side, unobserved by parties in front. Parties in front pause; man behind stops; and here we draw the veil."

Romance could lead to only thing one, as the paper observed in June: "Now that the marriage boom has been inaugurated, it is in order that the boys keep it going in good style, (providing the girls are willing)."

Two persons were willing. After Miss Mollie Turner and William Kirwin got married in the town hall, everyone moved to a house, where they ate and drank to "the health and prosperity of the happy pair in 'a varied assortment of cake and wine. Congratulations, handshakings, and some kissing, (by the ladies) were indulged until nearly midnight, when the guests departed. . . . During the evening Kirwin & Flynn's Saloon was open to the public, and so was all the liquid refreshments it contained, everything being free gratis for nothing. . . ."

BUT THE DISTRICT could also be fairly violent. Two Daggett men were arrested, tried, convicted, and fined for firing their pistols. "Pistols are apt to languish peacefully in the pockets of their owners in the future unless intended for effect. . . ." At a Calico saloon in April, James Jordan stabbed Pat Oday in the back with a butcher knife. Jordan had been drinking and tried to settle a grudge. Jordan was taken to jail in San Bernardino.

But vice was a problem to be winked at. Calico's best citizens were shocked to learn that Justice E.S. Williams had ordered the prostitutes of the Dance House arrested again. They quickly petitioned the local deputy district attorney, C.J. Perkins, to give up prosecuting the prostitutes. ". . . It is the impression in Calico that the above characters are receiving more punishment than is due them and that it is no worse for them to ply their 'avocations' on the main street of Calico than it is for the demi-monde to flourish on some of the principal streets of San Bernardino in the midst of respectable families."

Crime could sometimes be a matter between friends. Mike Sullivan and John Brown got into a fight while playing poker in Andy Laswell's saloon one Sunday. Sullivan accused Brown of cheating and grabbed all their money, about $40, and started running. Brown overtook Sullivan. In the struggle, Sullivan ran his arm through a store window and cut the main artery of his wrist. Sullivan was taken to a doctor's office, where his wound was bandaged thoroughly. Sullivan gave up most of the money the next day. "Ill gotten games are dearly won," the Print moralized.

ONE OF THE MOST BIZARRE INCIDENTS took place at the May Day Ball and Strawberry Festival, held at the town hall. The festivities began peacefully enough with a Maypole dance and the crowning of the Queen of the May. That night, teacher A.L. Hamilton found himself sitting with one of Mrs. Harwood's daughters, Rose, enjoying refreshments. About two dozen couples were dancing to throbbing music while Cupid was making his rounds.

Trouble loomed about 2 o'clock in the morning, when mine superintendent James Patterson was called outside. Two friends, James Marlow and W.E. Stoughton, accompanied him. Just outside, the three were pelted with eggs and perhaps a rock or small sandbag. Patterson sprang into action. He chased one disheveled assailant, W.H. Foster, through the hall, firing wildly. Dancers scattered, tables were overturned, the music stopped. A reporter wrote that the "scene in the hall was one of confusion and distress, several ladies fainting, all of the women and children being greatly alarmed. . . ." Patterson's bullets lodged in the walls and ceiling, even in a nearby Chinese restaurant.

The citizens were "greatly incensed." Foster and Marlow were arrested, then released on bail. In justice court, Foster pleaded guilty to assault and was fined $20; Marlow changed his plea to guilty and was fined $50; Stoughton was tried by a jury on a misdemeanor charge and acquitted.

BUT CRIMINAL INCIDENTS were minor compared to mining accidents. They tended to be gruesome, if not fatal. In mid-July, miner John Halley fell from a level of the King Mine and was severely bruised; he would recover with difficulty. Days later, miner John McDonald was .fatally injured while checking an unexploded charge. The blast threw up rocks and blew out both eves, mangled his arms, broke one leg. Doctors were called at once and "did everything in their power to alleviate his pain." After suffering "untold agonies," McDonald soon died.