The Last Antelope

Introduction

The historical record of the presence of antelope in the Antelope Valley is continuous and spans over 100 years. The earliest recorded sighting was by Lieut. John C Fremont during his exploration in 1844 and probably the last sighting was by Bill Barnes, a local rancher, in 1948. Some 13 collected sightings and tales lie in between. Though some are probably exaggerated, there can be no doubt that antelope were present in the valley. The continuity between the independent reports can lead to no other conclusion.Until recently, the archaeological record has been quiet on the subject. There was no evidence that the prehistoric Indians occupying the Antelope Valley and the surrounding mountains utilized antelope as a food source. The reason for this silence was probably because few of the bone fragments recovered from the minicamp in habitation sites had been analyzed by a specialist. This has now been done to a limited extent. Future work will tell if antelope were rare were common, but their presence, in whatever numbers, is indisputable.

Disappearance

There doesn't seem to be any single factor that caused antelope to disappear from Antelope Valley; it was probably a combination of environmental changes and outside pressure. Competition with domestic animals, especially sheep, for the available food and water started in the early 1880s. Antelope are adapted to large areas of open land in the intensive farming and widespread fencing that began in the late 1800s got the valley into many small sections. One often repeated tale is that the completion of the Southern Pacific railroad through Antelope Valley in 1876 The antelope from making their seasonal migration because they would jump the tracks. When the pressure of being hunted as pests and as a food supply is added, it is no wonder that the antelope are extinct in the Antelope Valley.

Domestic sheep were tough competion for available food

Archaeological Record

Remains of pronghorns have been found in at least one archaeological site in the Antelope Valley. In 1977-78 Mark Sutton led a field class from Cerro Coso College in the excavation of the site along the base of the foothills of the Tehachapi Mountains several miles west of Rosamond. The site is apparently part of a complex of sites which includes a major prehistoric village. The village itself covers several acres, has a very deep midden deposit, contains subsurface structures, and has a prehistoric cemetery. The site which Sutton excavated in 1977-78 was perhaps a peripheral area; the evidence indicates its primary function may have been for meat processing, the meat having been collected in large rabbit drives.

Tehachapi mountains

At the site in question, three test sets were excavated from which more than 8000 animal bone fragments were collected. The bone collection was analyzed by Robert Yohe (1984), a faunal analysis specialist at the University of California at Riverside. From his analysis came the first indisputable evidence for prehistoric pronghorn exploitation by the Indians of the Antelope Valley.

Black-tailed Jackrabbit

All of the bone fragments that Yohe could identify down two of the species level, the vast majority (97.8%) were black-tailed desert hare (Jackrabbit). Compared to the 1279 fragments of Jackrabbit bone, only 10 pieces of pronghorn bone were identified. While the small number of pronghorn bones may at first glance seem to minimize the importance of the species to the aboriginals, Yohe showed that if one considered the amount of usable meat represented by each bone fragment, then the contribution of the pronghorn became significant indeed. One pronghorn bone represents a much greater amount of meat than one jackrabbit bone. Based on the remains analyzed, pronghorn exploitation may have provided 50% of the mammal meat eaten.

Stone and bone tools

Besides the evidence based on quantities and percentages, to the pronghorn bones showed evidence of butchering and marrow extraction. Parallel cup marks, produced by flaked stone butchering tools, were visible on to pronghorn leg bones, and one of the leg bones was split open along its length were two percussion marks were evident, indicating the shaft had been hammered by forceful blows.

Historical Record

Lieut. John C Fremont of the US Army Topographical Corps was a trained observer and A meticulous journal(Jackson and Spence, 1970). In 1843-44 he led the first scientific exploration of the Far West and Pacific Coast region to be conducted by the United States since Lewis and Clark in 1804-06. Towards the end of his journal entry of April 15, 1844, Fremont Road, "... several antelopes were seen among the hills, and some large hares ...... by observation lat. 34° 41' 42" North, longitude 118° 20' 00" West...". The party had started from a camp near Oak Creek Canyon in this hatchet be mountains that morning and travel generally south through what is now Antelope Valley to a camp on Portal Ridge opposite Elizabeth Lake.

Elizabeth Lake

William I. Kip, the first Episcopalian Bishop of California, describes his trip through Antelope Valley, "We had a long hot dry all day over the plains. There was no timber except in one place, where the plains were covered with kind of a palm for a space of 2 miles. We saw numerous herds of antelope."

The Pacific Railroad House of Representatives report has this statement, "... the entrance to San Francisquito Pass from the Great Basin is not striking, but it rises gradually into the foothills. The party came light on a herd of 150 antelope near the mouth of the Canyon."

The prominent author Charles Nordhoff (1872), describes the floor of the Antelope Valley," the Tehachapi Pass by which the Southern Pacific Railroad is to pass from Bakersfield into the Mojave plain is part of the Tejon Rancho, and I came to drive into the great plain which is just now the home of thousands of antelope."

Rolling hills in the Antelope Valley plain

In a newspaper article in the May 7, 1915 issue of the Ledger-Gazette, Margarita Heffner wrote, "Antelope Valley was correctly so named, for great numbers of antelope were here. Many times have great droves, thousands in number, roamed over these hills and valley." Margarita Heffner came to Leona Valley as a little girl in 1863 and spent most of her life there.

In the Antelope Valley Press, February 14, 1984, Mr. A. H. Shoemaker said that he passed through Antelope Valley in 1882 and that he saw 40 wild horses, antelope in large herds, and deer.

Mule deer

John D. Covington, a very early rancher in the area, tells us in the April 18, 1915 issue of the letter is that when he was a boy, he and 30 Cowboys gathered together, as nearly as they could count, 7000 antelope. Must've been in the early to mid-1880s as he was born in 1867. Later, in a letter to his niece in 1947, Mr. Covington modifies this, to, " more of an estimate, the one that indicates the immense herds that once roamed the Antelope Valley" and goes on to tell of a storm in the 80s with very heavy snow that he believes destroyed most of the antelope (Settle, 1963). In the 1940 7G also says, " for several years there was a small band of antelope in the west end of the valley, but they were killed off one by one. Some of them got 'hung-up' in the fences, and others were killed by settlers. They became very wild and in recent years I have not heard of any at all." (Settle, 1963)

Pronghorn could jump, but did not care to and would get hung in fences

Pronghorn could jump, but did not care to and would get hung in fencesMaurice James Reynolds arrived in Lancaster on November 20, 1887 and went to look at some land about 8 1/2 miles east of town. He writes, "On our way back to Lancaster, 2 miles south of what is now known as the Reid Rancho, we saw twenty seven antelope." (Settle and Settle, 1984)

In a newspaper article in the Antelope Valley press, July 16, 1953, Emory kid, who came to Antelope Valley in 1891 when he was six years old, remembers that in the 1890s there were ample peer in the foothills, and antelope, while not plentiful, were often seen grazing with the cattle in the Valley.

Charles Kellogg, an early valley rancher, believed he had seen some of the last antelope in Antelope Valley (Strandburg, 1955). In about 1906 he relates that he was in a buggy out near Fairmont when he saw some animals circling. Stopping his team he saw, as they drew nearer, that they were antelope. He waited, hoping to get a better look, as even then antelope were scarce.

The Antelope Valley Press, February 14, 1984 reported that in 1921 the Ledger-Gazette newspaper reported that Los Angeles County officials were going to remove the last surviving antelope from the area and house them in an Eagle Rock park and that the Lancaster Chamber of Commerce argued against this proposal before the county supervisors.

The Antelope Valley Press, February 14, 1984 reported in 1923 Neenach rancher John Barry reported that his dogs cornered two small antelope.

Habitat near Neenach

The hunting of antelope was not regulated before 1852 in California, after that the season was closed for six months out of the year in a few counties, and in 1883 the hunting of antelope was prohibited. In the San Joaquin Valley antelope are considered pests by ranchers who imported commercial hunters from San Francisco and Oakland to "clear the range of these pests".

They were so nearly exterminated that only remnant bands in Western Merced County and in Antelope Valley, in northeastern Los Angeles County, survived (Popowski, 1959). They hung on until the early 1930s.

In an address to the West Antelope Valley historical Society on April 9, 1985, when Ralphs, a Gorman area rancher, said he had last seen antelope in Antelope Valley about 1937, but that his friend, Bill Barnes had seen some later than that.

Bill Barnes related what is probably the last appearance of antelope in the Antelope Valley in an address to the West Antelope Valley Historical Society in March, 1985. As he relates it, when he returned from military service in World War II there were four antelope in the vicinity of the Quail Lake pumping station. As a young man yet seen several herds of 25 to 30 antelope on the Tejon Ranch. His father felt the decline was due to an attempt by the Department of Fish and Game to move some of them to an area near Susanville, California. Cowboys from the Tejon Ranch rounded them up, but most of them didn't survive the ordeal. He has the horns of what he thinks was the last antelope in Antelope Valley.

Tejon Ranch winter pasture

Conclusion

By reviewing historical accounts and archaeological analysis, there can now be no doubt that pronghorn antelope did indeed occupy Antelope Valley. From the mid-19th century through the first decades of the 20th, the number of sightings and the reliability of his sources is conclusive. From the archaeological record, the evidence is more scanty, but nevertheless compelling there is no longer any doubt about their former presence.The Antelope of Antelope Valley

By Bruce Love & William H. De Witt

Antelope Valley History

The Journal of the West Antelope Valley Historical Society, Vol 1, No. 1 - 1988

Leona Valley, California

Pronghorn

CDFW photo

Pronghorn once existed throughout the entire central valley of California. Now they are mostly found in northeastern California.

The Department has made efforts to re-establish herds in central and southern California. The Pronghorn Management Program's objectives are to maintain healthy herds, provide a variety of recreational activities and to minimize conflicts with humans.

Species description

The antelope or pronghorn of North America is not related to the true antelope of Africa, but is the only existing representative of the hollow horned ruminant family Antilocapridae. specimens brought back by the Lewis and Clark expedition in 1806 were given the scientific name Antilocapra americana, and ever after were known as antelope. The name "pronghorn" comes from the single branching or forking of the horns.Antelope are small animals, only about 3 feet high at the shoulder, and of a bright font color with white on the neck, chest, underparts, and buttocks. The males have black horns rising vertically upwards immediately above the eyes while the females are either hornless or have small rudimentary horns. The horns, which are shed once a year, are made of cells similar to skin cells and are formed over bony cores that are not shed. Due to their thinness and brittleness, shed horns seldom last more than a season or two; which may account for the very few finds of antelope horns.

Habitat

Antelope inhabit the open plains of the temperate districts of the Western North America, where they were formerly very abundant. They are predominantly browsers who range over extremely large areas. Keen eyesight and speed are their main defense against predators. They can run long distances at speeds of 20 to 30 miles per hour and are known to be capable of bursts of 50 mph. They seem to be psychologically averse to jumping, though they are physically capable of jumping and have been observed jumping 6 foot fences when under great stress.Ecology - High Desert Plains & Hills

Native People

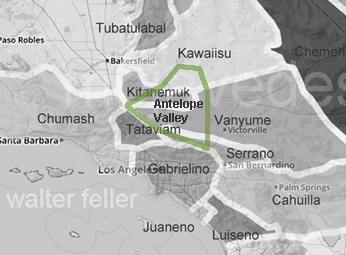

Related Indian territories map

Kawaiisu

Kitanemuk

Vanyume

Serrano