adapted from;

SECTION III: INVENTORY OF HISTORICAL RESOURCES THE WEST SIDE

The Valley Floor - Stovepipe Wells Hotel - History - Linda Greene

The History of Stovepipe Wells & the Death Valley Toll Road

Old Stove pipe Wells

Long before the present Stovepipe Wells resort was conceived of as a viable tourist operation, the site now referred to as old Stovepipe Wells was a life-saving source of water in the arid desert land of northern Death Valley. Situated on the eastern edge of the sand dunes about five airline miles northeast of the present hotel site, these two shallow pits dug into the sandy floor were undoubtedly originally utilized by the Indian inhabitants of the valley prior to the memorable trek of the '49ers that opened the country to white penetration. Their central location would have made them accessible to Indian groups either crossing between the Amargosa Desert and the Cottonwood Mountains via Daylight Pass, or traveling north or south along the valley's central axis. Originally unmarked, and its whereabouts often obscured by layers of blown sand, the well's location was probably first known only through word of mouth, making its detection by thirsty prospectors wandering up and down the valley an. often desperate and time-consuming task. Eventually it occurred to some enterprising individual, who had access to the necessary materials, to stick a length of stovepipe a few feet into the water source and thus insure easy discovery of the site from all directions. [3]Heavy usage of the well by white men did not actually occur until the mining booms, in Rhyolite, Nevada, and Skidoo, California; the intense excitement and awareness of commercial opportunities they generated initiated a steady and continuous stream of travel over the intervening sixty miles or so of steaming desert. In such a desert environment all springs and water sources are cherished, but Stovepipe's location halfway between Rhyolite and Skidoo seemed to make it a natural waystation for the area also. Sometime probably early in the 1900s a first attempt was made to make of the wells something more than a brief rest stop.

Sensing that the increased traffic along here could become a source of revenue, some hardy businessman or inventive prospector dug himself a cellar space out of the shifting sands, measuring about eighteen by twelve feet, which he then surrounded on three sides with four- to five-foot-high walls fashioned from beer bottles stuck together with mud. Several inches of earth over tarp-covered timbers insulated the roof. from the burning desert sun. Initially concerned only with dispensing a limited assortment of foodstuffs along with a liberal amount of beer from the Tonopah brewery (kept reasonably cool in a tub covered with soaked sacks or tarps), the proprietor soon acquiesced to repeated demands for cool lodging facilities and installed two beds in his cellar for use by overnight visitors.

The water available from the wells was not what would be termed delightfully refreshing, as discerned immediately from one man's account of his experiences after drinking the "poisoned water" of Stovepipe Springs:

-

My canteens were exhausted when I arrived there [old Stovepipe Wells], and I disregarded the admonition and drank. The water is very low in the spring, is of a yellowish appearance and intensely nauseating in taste. Its odor is very disagreeable, and it can be smelled for half a mile away. Nevertheless, I filled my canteens, and drank of it while there. As I proceeded on my journey my legs became unsteady and I found it difficult to continue my usual pace. I lay down thinking to gain strength, but no improvement was noticeable. The distance between Stove Pipe and Hole-in-the-Rock is about 14 miles, and I fully realized that it was by all odds a case of make this or die . . . . I struggled forward, my legs becoming more and more uncertain. In addition to this everything was getting dim before me, and I appeared to be rapidly losing my eye sight . . . . I could no longer walk and the only means of locomotion left me was to crawl on my hands, and knees. I was almost blind, too . . . . I was 36 hours in making the 14 miles between the two points, and it looks more like a miracle than anything else that I am. alive to tell the tale. [3]

With the initiation of stage and freight service between Rhyolite and Skidoo in 1906, it became apparent that a more permanent and better-stocked waystation was needed to adequately provision and succor the additional travelers. By February 1907 Stovepipe Wells, in addition to being the one-night stopover on the Kimball Bros. stage route between Rhyolite and Skidoo, was also the first telephone office in the valley. According to J.R. Clark, superintendent of construction on the Skidoo-Rhyolite road and one of the proprietors of the Stovepipe roadhouse, affairs at Stovepipe are more than satisfactory. There is a commissary tent, a boarding house, lodging house and several additional tents, a corral and feeding stable and accommodations in every respect for pilgrims crossing the hot sands. The spring is now inclosed and the water is consequently much improved . . . . The water is the only fresh water within several miles . . . . The road house at this point is an absolute necessity and facilitates travel from Rhyolite, providing a stopping point at the end of an easy day's drive. [5]

Two months later improvements to the complex were being made, and a feature article on the station in the Rhyolite Herald's pictorial supplement presented a clear picture of what services could be expected there:

-

The rusty stovepipe is gone, and there stands in its place a full-fledged road house, way down in the depths of the desert isolation. Many a prospector, tired, worn and weary, has travelled far to the protection of this water hole, marked only by the single piece of pipe; perhaps many a prospector has drunk from its slimy waters never to rise again, being too faint, too famished, to consider the advisability of bailing out the hole and waiting for a fresh supply. The water at Stovepipe is good., provided it is frequently drawn off, but alike most desert water holes it soon becomes stagnant and unfit for use. The coming of the road house has eliminated all the bad features of the water, which is now considered of the best.

The Stovepipe road house is quite an up-to-date place. The, equipment includes a grocery, eating house, bar, lodging house, corral, stock of hay,, grain and provisions,--a little community in itself where travellers may find rest and food for themselves and their beasts. Just now, decided improvements are in progress. A fly is being added to the main tent, walls are being dug, bath room installed, and a pump is being placed to take care of the water. Hammocks will be added for the comfort of guests. Good accommodations have been provided for ladies. Free water is furnished, and every day the place is alive with freighting outfits, etc. going between Rhyolite and Skidoo. Stovepipe is 25 miles from Rhyolite; the half-way station. Meals are 75 cents; beds, 75 cents. The telephone. connects Stovepipe with the outside world, via Rhyolite. [6]

Perhaps showing signs of getting carried away with the success of their venture, the owners of Stovepipe were Seven contemplating eventually turning the area into a winter resort:

-

The water is believed to possess great medicinal properties, the winter is as a delightful spring, and with the addition of comfortable bungalows, houses of entertainment, out door games, on the hard baked sands, and many other features that might be added, Stovepipe could be made a place where those in delicate health or suffering from pulmonary troubles, might find permanent relief. If the sun cure has merit, it could be worked to the limit at Stovepipe. . . [7]

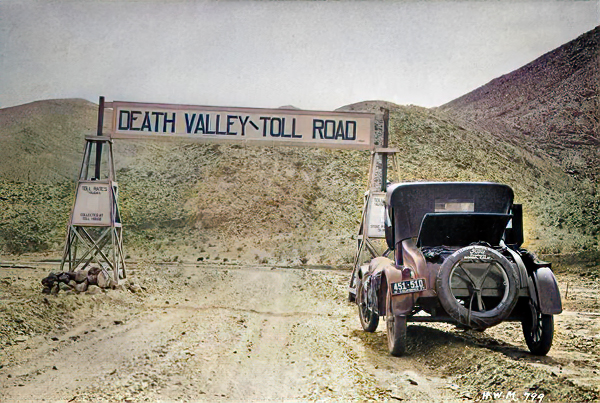

Eichbaum Toll Road Brings Visitors to Death Valley

Herman William Eichbaum, born in Pennsylvania in 1878, received a degree in engineering at the University of Virginia before the lure of the West brought him to Rhyolite, Nevada, during its initial bonanza days. Blessed with an open and inventive mind, Eichbaum's engineering talents soon surfaced with his design and construction of the first electric plant in that young city in 1906. Soon turning to mining exploration of the Ubehebe and Goldbelt areas, Eichbaum acquired a taste for prospecting and an appreciation of the beauty and potential of Death Valley that stayed with him all his life and that eventually determined the direction of his future endeavors. When Rhyolite faded, Eichbaum went to southern California where he eventually married a society girl, Helene Neeper, and turned his inventive talents toward creating popular recreational activities on Catalina Island and at the seaside resort of Venice.

During his sojourn in Death Valley Eichbaum had envisioned the recreational potential of the area and had dreamed of constructing a resort among the buttes east of the sand dunes and overlooking Stovepipe Wells. Now, bolstered by several years experience in catering to the public., and well-versed in what the public demanded in its entertainment facilities, Eichbaum determined to make his dreams of opening up Death Valley to tourism a reality. Rejected by the Inyo County Board of Supervisors when he petitioned to construct a toll road from Lida, Nevada, into Death Valley via Sand Spring, Eichbaum alternatively proposed a route over Towne Pass. But still the supervisors were loathe to contribute at taxpayer's expense to what seemed to them such an ill-conceived venture.

Undaunted even after another application was voted down, this time for a franchise to build two toll roads at his own expense, and in an effort to alleviate previous objections, Eichbaum revised his plan to include only construction of a road from Whippoorwill Springs (Darwin Wash) across the Panamint Valley and over Towne Pass to old Stovepipe Wells. [8] Supported by a petition signed by several hundred persons, including representatives of the borax company and even Death Valley Scotty, Eichbaum's application was at last granted by unanimous vote. [9]

Although getting this far must have seemed quite a project to the young visionary, the hard work was only just beginning. After three viewers appointed by the Board of Supervisors, in consultation with an engineer selected by Eichbaum, had decided on the route over Towne Pass and the best method of building the road, construction work began:

-

A Mr. Miller, Eichbaum's right-hand-man, was superintendent over a crew of six to eight men, including a driver, a grader, several rock throwers, and a cook. Few of them stayed throughout the job . . . . The first road cut was made by a 30-Caterpillar tractor pulling a seven-foot road grader. Then it was widened to a passing width. Rocky outcroppings often determined the width of the road as well as its contour. No blasting was done. As one of the crew described it, they "kinda detoured around" the rough canyon of the present route toward the summit. [10]

In spite of frustrations over mud and washouts that often delayed supplies and construction work, the labor slowly progressed. The floor of Death Valley was reached by spring, and attempts we're then made to clear and grade the roadbed on through to the east side of the valley. It, was not long, however, before the futility of combatting the constantly shifting sands was realized, and the grade had of necessity to be stopped at the sand dunes 4-1/2 miles short of Eichbaum's long-dreamed-of goal. Certification of completion of the toll road was made on 4 May 1926, after which the county supervisors fixed the toll rates between Whippoorwill Springs and Stovepipe Wells as follows: $2 for each auto or motorcycle; 50˘ for each occupant of a truck, trailer, wagon, auto, or motorcycle; $1 per head for each animal, whether driven or led; with rates for trucks, wagons, and trailers to be determined by tonnage. [11] Revenue from the tolls was put in a fund for road maintenance.

The new road into Death Valley, although rough and containing curves that were often difficult for cars to negotiate without considerable backing, was acclaimed for providing direct access to the valley from Los Angeles via Owens Valley, enabling thousands to finally experience first-hand the oft-mentioned scenic splendors and unrivalled panoramas of the region. Eichbaum's immediate plans envisioned sightseeing buses leaving Los Angeles each morning and staying overnight at Lone Pine before continuing on to Death Valley for the next night's stay. The return trip would then be started the following day back to Lone Pine. In addition, Lone Pine was visualizing construction of a road west to the base of Mount Whitney, enabling a one-day ascent of that peak. It was thought that the double drawing-card of visiting the highest and lowest spots in the United States within the space of only a few days would be irresistable to tourists. [12]

(3) Construction of the Resort Begins

With the details of tourist travel to Death Valley worked out, Eichbaum's attention could now focus on construction of his resort, the first unit of which was projected to cost around $50,000, his intention being to add more facilities as the occasion warranted. After Eichbaum's original plan to build a hotel in the buttes east of old Stovepipe Wells turned out to be impractical, an alternative decided on was to initiate construction near the wells themselves. But even this compromise location was doomed to disappointment:

-

One day six trucks of lumber for the new development were reported arriving at the sand dunes; though we didn't believe it we drove up there to see what it was all about. The proposed route to the Wells lay north of the big dunes and one truck was out there sunk deep in the sand as the others waited cautiously on firm ground for Eichbaum's arrival. He showed up finally, had a long look and then told the drivers to dump their loads where they stood without a chance to reach the wells one place was as good as another. Thus, the site was selected. . . . [13]

It was Eichbaum's contention that in the temperate climate of Death Valley solid frame structures were unnecessary, so the premier unit of his resort consisted of modified tent houses with walls that were beaverboard below and screened on the upper portion, with roll-up canvas awnings available for any further protection against the elements that was deemed necessary. Advertising for the resort and the connecting bus service was immediately started in Los Angeles, stressing such amenities as electric lights, running water, scenic tours, and topnotch service. The original camp consisted of twenty small cabins or "bungalettes" and some larger buildings supplemented with army tents. A revolving beacon light on the roof of the main building served to guide wanderers to the oasis. In these beginning stages of the hotel's development the toll road ran between the main building and the guest cabins and on into the sand dunes.

Bungalette or Bungalow City, as it was familiarly known for a short while, opened for business 1 November 1926, operating on the American plan. The first party of tourists arrived a few days later. Despite the relative luxuries and modern conveniences available here, the basic necessities were still important, and in a manner demonstrating remembrance of the agonies suffered by earlier and thirstier visitors to Death Valley, on 15 November "a crowd of merrymakers dined and danced in celebration of the formal opening of a new 24,000-barrel water well," making possible an additional 1,000 gallons of water an hour. [14]

By the end of November the virtues of the area and of the resort were being extolled in a flowery descriptive tribute by the automobile editor of the Los Angeles Examiner

-

Death Valley, always mysterious, intriguing and beautiful, until this time has been practically closed to the general motoring public. Now it can be reached and seen in its entirety and in absolute safety[,] comfort, and convenience, either by stage or by private car . . . . It [Stovepipe Wells Hotel] is a city of fifty bungalettes. Their snowy white sides, offset by green and white canvas sun shades, with green roofs, form a vivid contrast. to the gray-black sands. At one end of this bungalette city is a restaurant where a former chief [sic] of the St. Catherine Hotel at Catalina serves tasty delicacies, while radio and Victrolia [sic] entertain. At the other is a store, electric light plant and baths. Across the street men toil with mortar and sand, building tennis courts, a swimming pool, which will be canvased [sic] covered and farther over a nine-hole golf course, plus a landing field for airplanes. This landing field is important, for when completed Eichbaum proposes to put into service passenger planes from Los Angeles, with a combination trip that will make a visit to this country most unusual. [15]

Added entertainment possibilities he failed to mention were the trail rides complete with pack animals and with old-time famous prospectors as guides; or for those unaccustomed to. such a rigorous mode of transportation there were large Buick sedans available for sightseeing in comfort. A stage service employing huge Studebaker cars equipped with the latest appointments daily left Los Angeles on tours to Death Valley via Lone Pine. A year-round operation, in the summer the cars took people to Mount Whitney and other scenic spots in the Sierra Nevada.

By far the largest and most entertaining social event of the year, eclipsing even the opening day, was the Thanksgiving turkey dinner to which all the long-time residents of the valley were invited, the guest list including such notables as Shorty Harris, John Cyte, Bill Corcoran, Jack Stewart, and a host of others. From this time on the resort became a favorite rest stop and gathering point for area prospectors, a place where they knew they would always be welcomed and cared for. [16]

This life Eichbaum had chosen was not an easy one. Despite the widespread and enthusiastic campaign inaugurated to promote tourism in the area, there were still many who remained unconvinced that the desert offered much potential for positive enjoyment. This was especially disheartening to one who was such a firm supporter of the area's natural and historical resources. Another frustration was the basic mechanics of operating an expanding complex in such an isolated area. Most supplies were hauled in from Lone Pine, a long and exhausting trip, while laundry had to be done at Beatty. Because of the salty and brackish content of the water--from the hotel wells, cooking and drinking water had to be imported from Emigrant Spring. Hotel employees were hard to keep in this isolated area, the necessary complement consisting of a clerk, bellhop, cook, two waitresses, and two guides. Some if not all of these workers were evidently blacks, one woman visitor commenting on the "army of colored help all dressed in white duck." [17] The road was kept in shape by a crew of five maintenance men.

Easter Sunrise Celebration the First of Several New Tourist Services

Probably the biggest boost to tourism in Death Valley was provided by the first Easter sunrise service for the unknown dead of the valley, organized by the Eichbaums to take place on 17 April 1927 in the sand dunes northeast of the resort. The program included a stirring address "dedicated to the memory of the courageous men and women who braved the terrors of the desert in bygone years" [18] and delivered near a large wooden cross set on the crest of the highest sand dune; 100 schoolchildren strew desert flowers over the dunes, the entire program closing with a rousing rendition of "Onward Christian Soldiers" as the sun rose over the Funeral Mountains. [19] The event was so popular and attracted so many people from Los Angeles by private car and motor tour that the service became a ritual each year. [20]

By late October 1927 plans were being made for an ice plant at the resort, and a new unit of rooms being contemplated was to have double walls with a six-inch space between through which cool air would be forced from coils connected to the ice plant. Another ritual repeated this month was the "desert rat" Thanksgiving Dinner, offering the crusty old-timers a tantalizing assortment of delicacies ranging from lobster from Catalina Island to a shank of wild mountain goat in addition to the traditional fowl. How times had changed for the likes of "Johnny-Behind-the-Gun" and "Shorty" Harris! [21]

Two innovations were introduced toward the end of 1929 and beginning of 1930. On 15 December 1929 the first passenger air service into Death Valley was begun. The 350-mile plane tour, in a tri-motored six-passenger sedan, provided its patrons with a view of Yosemite Valley and Mount Whitney before landing on the arid floor of Death Valley. Pack trains and motor cars with guides met the visitors at the Stovepipe Wells landing field and conducted trips to some of the various historical sites in the area. [22] Another enterprise Eichbaum became involved in was the construction of a road to Death Valley Scotty's Grapevine ranch, which would connect with the toll road near the sand dunes, reducing the distance to the ranch and Castle to only thirty-five miles from the present eighty-five-mile route via Beatty and Bonnie Claire. This project opened to the tourist trade not only Scotty's ranch and Castle but also the Ubehebe area, rich in scenic wonders and mining activity. [23] This road led north from the sand dunes toward Cottonwood Canyon, ran by the Indian burial mounds in this vicinity, and then cut across to the western base of the Funeral and Grapevine mountain ranges, which it followed directly to Scotty's ranch and Castle. The later modern highway to Scotty's Castle was superimposed over much of this route.

Toll Road Abolished After Creation of National Monument

It is tragic that the man to whom Death Valley owes so much for its popularizing as one of California's major attractions and most popular winter vacation spots should not have lived to see the region he loved so well become a national monument. A sudden attack of meningitis struck Eichbaum at the age of forty-nine and resulted in his death a few days later on 16 February 1932. A year later, on 11 February 1933, the desolate but beautiful valley that had been the scene of so much hardship and so few rewards for so many became a national monument. Although Helene Eichbaum was continuing to run the Stovepipe Wells Hotel and toll road, cries were now being heard that toll charges were inappropriate for a national monument and that either the county, state, or federal government should take over the route and remove them. The loudest objections to the tolls were coming from Inyo County residents who, of course, utilized the route more often, and from miners who were currently working claims within the monument and frequently needed to visit them. It was felt that purchasing the road immediately and continuing to use it for a while would give the state time to thoroughly study possible alternative entrances into Death Valley from the northwest that might then connect with other state roads not yet built.It was hoped at first that the Inyo County Board of Supervisors could be persuaded to purchase the route, it appearing to be the most logical buyer for several reasons: first, Inyo County residents were the loudest protestors to the toll second, acquisition of the road would more clearly define a state route through Death Valley from Shoshone to Independence, thus financially benefitting towns along the highway; and third, Inyo County was more indebted than either the state or federal governments to the pioneer road-building work accomplished by Eichbaum and might be more liberal in the purchase price. [24]

It was the California Division of Highways, however, that finally purchased the 30.35 miles of toll road from Stovepipe Wells to Darwin Wash for $25,000 in December 1934; the seventeen miles of the newly purchased road located within the monument boundaries were subsequently turned over to the NPS. Although the route over Towne Pass was a little too narrow to be easily negotiated by cars and the grades were a bit too steep, the state decided that this was still the only logical entrance point into Death Valley from the west. Only slight changes were made to the route near the summit so that it would be more easily navigable.

The Stovepipe Wells Hotel has gone through several changes of ownership, finally being sold in 1966 by the General Hotel Corporation to Trevell, Inc., a firm operating stores and filling stations in Yellowstone National Park. The NPS has now taken over ownership of the resort. [25]

Present Status (1978)

The Stovepipe Wells Village complex today offers patio rooms, motel rooms, and deluxe units with a commanding. view out over the sand dunes toward Death Valley. Also present near the main building for visitor pleasure are a swimming pool, restaurant, and cocktail lounge, while across the street are a store, gas station, and a large campground with trailer hookups. Wells drilled in the 1940s now provide potable drinking water. Here and there on the grounds are several relics reminiscent of the monument's early mining days, including an arrastra, ore cars, an old wagon, and even a couple of "mountain canaries."c) Evaluation and Recommendations

The Stovepipe Wells resort of today, situated in the north-central end of the monument about sixteen miles east of Towne Pass and adjacent to the sand dunes, is a far cry from the small tent camp opened in 1926 by Bob and Helene Eichbaum. The rude tent cabins have given way to pleasant air-cooled rooms, while the rough and narrow Eichbaum toll road has been replaced by a stretch of modern paved highway over which visitors can easily speed between beautiful Owens Valley and the monument. The significance of the Stovepipe Wells Hotel site lies in its association with Bob Eichbaum who first recognized the potential of Death Valley as a winter resort and spent thousands of dollars turning it into one of California's major tourist attractions. Until his efforts were begun, Death Valley was for all intents and purposes inaccessible to the general motoring public who were deterred by the lack of good roads and of dining and sleeping facilities in the area.

By expending a considerable amount of time and money on advertising and on initiating sightseeing tours in this desert region, Eichbaum was able to attract the Los Angeles crowd, whose utilization of the area as a winter resort, Eichbaum knew, would ensure a prosperous future for the valley whose beauty he wished all to enjoy. Eichbaum's interest in encouraging the tourist trade in the area was certainly not mercenary; he probably never totally regained reimbursement for all his many expenditures. His dedication to good service is shown by the fact that he even kept a crew at Stovepipe through the summer months when the resort season was over to provide aid for those inexperienced visitors who might enter the valley and become victims of the heat. [26]

Because of this and similar altruistic actions on the part of both husband and wife, Eichbaum was one of the valley's best-liked residents, beloved by tourists and prospectors alike. The debt owed him by the monument and by Inyo County residents, to whom his business ventures incidentally brought added profit through increased traffic in the Owens Valley area, is immense. He truly fulfilled his vision, conceived during his early prospecting days in the Panamints, "that some day he would go back and open Death Valley, with its beauty, its mystery and history to the world." [27]

The Stovepipe Wells Hotel site was recommended for inclusion on the National Register as being of regional significance. The publicizing of the hotel as the first resort in Death Valley lured vast numbers of tourists there, whose delight in the area and appreciation of its natural and historical resources eventually led to designation of the area as a national monument. The present buildings on the site, however, are not historically significant, having been extensively remodeled and changed over the years. The placement of an interpretive marker on the resort grounds giving some of the hotel's early history is recommended. The Eichbaum toll road (present California State Route 190) has been nominated to the National Register as being of regional significance. Portions of the original trace can still be seen near the modern resort structures. The old Stovepipe Wells site on the 3-1/2-mile-long unpaved road connecting State Highway 190 and the Scotty's Castle road, is also eligible for nomination to the National Register as being of local level of significance. It functioned as an important early waterhole and later was the site of an essential waystation serving the freight teams, passenger stages, and pedestrians travelling back and forth between Rhyolite and Skidoo in the early twentieth century.

(Note: The Stovepipe Wells Hotel and Eichbaum Toll Road have both been declared ineligible for the National Register by the State Historic Preservation Office due to a lack of integrity.)

Death Valley Historic Resource Study

by Linda Greene NPS

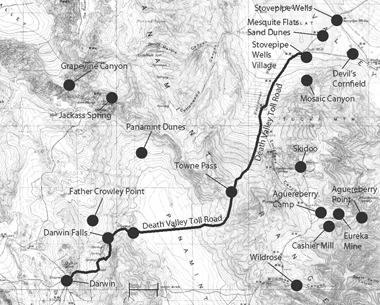

Map of Death Valley Toll Road

Map of Death Valley Toll Road

Illustration 256. Bottle dugout, old Stovepipe Wells, in the 1920s. From Margaret Long Collection, courtesy University of Colorado Library, Boulder.

Illustration 257. Stovepipe Wells waystation, taken by Veager and Woodward on Death Valley Expedition, 1908. Photo courtesy of DEVA NM.

Illustration 258. Present old Stovepipe Wells site. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978.

Illustration 260. Stovepipe Wells Hotel. Photo by Linda W. Greene, 1978.