Furnace Creek Inn

“Would You Enjoy a Trip to Hell?...You Might Enjoy a Trip to Death Valley, Now! It has all the advantages of hell without the inconveniences.”Considering Death Valley’s reputation as the hottest, driest, and lowest place in America, this April Fool’s Day, 1907 advertisement in the Death Valley Chuck-Walla—a local mining camp newspaper—was meant to be tongue-in-cheek. Yet only twenty years later, a luxury hotel was built that would help change Death Valley from hell-hole to tourist mecca.

The Furnace Creek Inn was built by the Pacific Coast Borax Company of Twenty Mule Team fame as a means to save their newly built Death Valley Railroad. Mines had closed and shipping transportation was no longer needed, but mining tourist pockets seemed a sure way to keep the narrow-gauge line active. The borax company realized travelers by train would need a place to stay and wealthy visitors accustomed to comfort would be attracted to a luxury hotel.

First opened for business in 1927, the Furnace Creek Inn was an immediate success. Unfortunately for the mining company, their railroad closed forever in 1930 when it became apparent tourists preferred the freedom of arriving to Death Valley in their own cars. None the less, the Inn remained popular and construction continued for the next ten years.

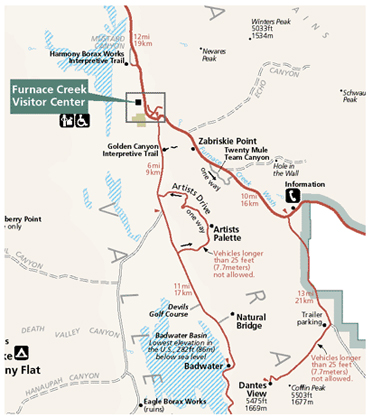

Designed by prominent Los Angeles architect Albert C. Martin and landscape architect Daniel Hull, the 66 room Inn sprawls across a low hill at the mouth of Furnace Creek Wash. With views over Death Valley and the Panamint Mountains to the west, the Inn’s location was well chosen but rather conspicuous. In less skilled hands the Inn could have been a visual imposition on the otherwise natural landscape, but Martin and Hull created a masterpiece in harmony with history and scenery. Red tile roofs, stucco exteriors, archways, arcades and tower were inspired by the old Spanish Missions on the California Coast. The Inn’s wings wrap around a lovely garden of palms and flowing water, a nod to both mission courtyards and the Hollywood image of a fantasy desert oasis. The lower levels constructed of local stone seem to be a natural extension of the alluvial fan pouring out of Furnace Creek Wash. The colors of golden stucco, russet roof tiles and turquoise window trim all match the badlands at Zabriskie Point and Artists Drive.

Even with amenities such as a warm spring-fed swimming pool, tennis courts and nearby golf course, the Borax Company realized the primary attraction for their resort was its location in Death Valley. An oasis of comfort and luxury in a wild and desolate desert proved to be irresistible to tourists. The mining company understood Death Valley’s rustic charms could be easily lost without some preservation. National Park status for Death Valley would not only limit damage from mining but also control excessive development (and competing hotels.) Tourists hesitant to visit such a morbid sounding place as Death Valley would know that it must be worth visiting if it was included with the nation’s other crown jewels like Yosemite, Yellowstone, and Grand Canyon. It would become a “must see.”

To promote the idea of Death Valley becoming a National Park, the company invited the Director of the National Park Service, Stephen Mather, and his assistant, Horace Albright, to visit Death Valley in 1926. Although Mather was impressed by the scenery and agreed it was of national park quality, he declined the request to help. He knew the battle to convince Congress would be difficult and was afraid his involvement would sour the deal due to his personal history. Prior to becoming NPS Director, Mather had worked for Pacific Coast Borax, and so had his father. To avoid scandal and accusations of showing favoritism, Mather suggested using the media to spread the word of Death Valley’s wonders and start grass-roots support for protection of Death Valley. Magazine and newspaper articles and a successful radio program—Death Valley Days—were all tools used by the Borax Company. After Mather’s death in 1930, Horace Albright became the NPS Director and felt free to promote the idea in Washington D.C. In February 1933, President Hoover signed a proclamation creating Death Valley National Monument. More than sixty years later, Death Valley finally was designated a National Park in 1994.

Today, the Furnace Creek Inn is still an oasis in the desert. Thanks to the foresight of the Pacific Coast Borax Company and the National Park Service, guests can enjoy the same untrammeled beauty of Death Valley that guests did back in 1927.

Source: NPS