Chapter XV

The Story of Charles Brown

Greenwater

The story of Charles Brown and the Shoshone store begins at Greenwater. In the transient horde that poured into that town, he was the only one who hadn’t come for quick, easy money. On his own since he was 11 years old, when he’d gone to work in a Georgia mine, he wanted only a job and got it. In the excited, loose-talking mob he was conspicuous because he was silent, calm, unhurried.

There were no law enforcement officers in Greenwater. The jail was 130 miles away and every day was field day for the toughs. Better citizens decided finally to do something about it. They petitioned George Naylor, Inyo county’s sheriff at Independence to appoint or send a deputy to keep some semblance of order.

Naylor sent a badge over and with it a note: “Pin it on some husky youngster, unmarried and unafraid and tell him to shoot first.”

Again the Citizens’ Committee met. “I know a fellow who answers that description,” one of them said. “Steady sort. Built like a panther. Came from Georgia. Kinda slow-motioned until he’s ready for the spring. Name’s Brown.”

The badge was pinned on Brown.

Greenwater was a port of call for Death Valley Slim, a character of western deserts, who normally was a happy-go-lucky likable fellow. But periodically Slim would fill himself with desert likker, his belt with six-guns, and terrorize the town.

Shortly after Brown assumed the duties of his office, Slim sent word to the deputy sheriff at Death Valley Junction that he was on his way to that place for a little frolic. “Tell him,” he coached his messenger, “sheriffs rile me and he’d better take a vacation.”

After notifying the merchants and the residents, who promptly barricaded themselves indoors, the officer found shelter for himself in Beatty, Nevada.

So Slim saw only empty streets and barred shutters upon arrival and since there was nothing to shoot at he headed through Dead Man’s Canyon for Greenwater. There he found the main street crowded to his liking and the saloons jammed. He made for the nearest, ordered a drink and whipping out his gun began to pop the bottles on the shelves. At the first blast, patrons made a break for the exits. At the second, the doors and windows were smashed and when Slim holstered his gun, the place was a wreck.

Messengers were sent for Brown, who was at his cabin a mile away. Brown stuck a pistol into his pocket and went down. He found Slim in Wandell’s saloon, the town’s smartest. There Slim had refused to let the patrons leave and with the bartenders cowed, the patrons cornered, Slim was amusing himself by shooting alternately at chandeliers, the feet of customers and the plump breasts of the nude lady featured in the painting behind the bar. Following Brown at a safe distance, was half the population, keyed for the massacre.

Brown walked in. “Hello, Slim,” he said quietly. “Fellows tell me you’re hogging all the fun. Better let me have that gun, hadn’t you?”

“Like hell,” Slim sneered. “I’ll let you have it right through the guts—”

As he raised his gun for the kill, the panther sprang and the battle was on. They fought all over the barroom—standing up; lying down; rolling over—first one then the other on top. Tables toppled, chairs crashed. For half an hour they battled savagely, finally rolling against the bar—both mauled and bloody. There with his strong vice-like legs wrapped around Slim’s and an arm of steel gripping neck and shoulder, Brown slipped irons over the bad man’s wrists. “Get up,” Brown ordered as he stood aside, breathing hard.

Slim rose, leaned against the bar. There was fight in him still and seeing a bottle in front of him, he seized it with manacled hands, started to lift it.

“Slim,” Brown said calmly, “if you lift that bottle you’ll never lift another.”

The bad boy instinctively knew the look that pages death and Slim’s fingers fell from the bottle.

Greenwater had no jail and Brown took him to his own cabin. Leaving the manacles on the prisoner he took his shoes, locked them in a closet. No man drunk or sober he reflected, would tackle barefoot the gravelled street littered with thousands of broken liquor bottles. Then he went to bed.

Waking later, he discovered that Slim had vanished and with him, Brown’s number 12 shoes. He tried Slim’s shoe but couldn’t get his 104foot into it. There was nothing to do but follow barefoot. He left a blood-stained trail, but at 2 a.m. he found Slim in a blacksmith shop having the handcuffs removed. Brown retrieved his shoes and on the return trip Slim went barefoot. After hog-tying his prisoner Brown chained him to the bed and went to sleep.

Thereafter, the bad boys scratched Greenwater off their calling list.

Slim afterwards attained fame with Villa in Mexico, became a good citizen and later went East, established a sanatorium catering to the wealthy and acquired a fortune.

Among the first arrivals in Greenwater was a lanky adventurer known to the Indians as Long Man and to whites for his ability to make money in any venture and an even more marvelous inability to keep it. He was Ralph Jacobus Fairbanks. Broke at the time, he was seeking the quickest way to a “comeback.”

Foreseeing that the biggest names in copper meant a rush, he had taken a look at the little stagnant spring with a green scum that was to give the town its name.

“Not enough water in it to do the family washing,” he decided and with uncanny talent for seeing opportunity where others would starve to death, he was soon peddling water at a dollar a bucket. He had hauled it 40 miles uphill from Furnace Creek wash.

A hopeful, but late arrival who expected to find the town crowded with killers was an undertaker who came with a huge stock of coffins. The prospect of a quick turnover seemed to guarantee success, but in two years Greenwater had exactly one funeral and he sold but one coffin. Disgusted he stacked the caskets in the center of his shop; left and was never again heard of.

Fairbanks came into town one day with his sweat-stained 16 mule team, noticed the abandoned coffins, picked out the largest and best and gave Greenwater its first watering trough, which was used as long as the town lasted.

Fairbanks soon made enough money to acquire a hotel, store, and a bar, which became a popular rendezvous. Fairbanks was born of well-to-do parents, in a covered wagon en route to Utah in 1857. Of the thousands who flocked into Greenwater, only he and Charles Brown were to remain in Death Valley country and wrest fortunes from America’s most desolate region. To Greenwater he brought his wife, Celestia Abigail, who shared his spirit of adventure, but fortunately for him she possessed a caution which he lacked. Among their children was a beautiful and vivacious daughter, Stella.

Fairbanks, who was of the quick, go-getting type, didn’t care for Brown. Born in the North, he was critical of the slow-moving, silent, 105young Georgian and unacquainted with the Deep South’s drawl, he referred to him as “that damned foreigner.”

The reputation of the Fairbanks camaraderie spread, and Mrs. Fairbanks, who understood the longing of a youngster for a home-cooked meal, invited Brown to dinner.

There were other young fortune seekers in Greenwater who were also occasional guests at the Fairbanks dinners—among them a Yankee from Maine—Harry Oakes, of whom the world was to hear later. Allen Gillman, known as the Rattlesnake Kid, because of his stalking rattlesnakes to indulge his hobby of making hat bands and trinkets, later to become associated with Bernarr McFadden. Wealthy young mining engineers. Bank clerks with futures. Brown apparently had none.

“He’ll get out of the country like he came in—afoot and broke,” rivals told Stella. So when romance came, there was still a long trail ahead.

Then came Greenwater’s first warning of trouble. A few miners were laid off; a few padlocks appeared on a few cabins; a few merchants complained. Soon it was noticed that the tinny pianos from which slim-fingered “professors” swept the two-step and the waltz were gathering dust while the girls lolled in empty honkies. But when Diamond Tooth Lil padlocked her door and joined the rush to a new copper strike at Crackerjack in the Avawatz Mountains the wiser knew that Greenwater was through.

With no guests Fairbanks told off on his fingers, departed patrons, mine owners, doctors, lawyers. “Just Charlie left. Wonder what’s keeping him?” Celestia Abigail knew. She knew that the big Georgian was desperately in love with Stella and didn’t care how many of her suitors left.

With mines closing and few official duties, Brown loaded a burro with supplies and with Joe Yerrin went on a prospecting trip. Their course led across Death Valley. They were caught in a heat that was a record, even for the Big Sink, and ran out of water. Fortunately they were within a few miles of Surveyor’s Well—a stagnant hole north of Stovepipe. The burros were also suffering and Brown and Yerrin staggered to water barely in time to escape death.

The well there is dug on a slant and looking down they saw a prospector kneeling at the water, filling a canteen and blocking passage.

“Reckon you fellows are thirsty,” he greeted. “I’ll hand you up a drink. Have to strain it though. Full of wiggletails.” He pulled his shirt tail out of his pants, stretched it over a stew pan, strained the water through it and handed the pan up to Brown. “Now it’s fit to drink,” he said proudly.

“It was no time to be finicky,” Charlie said. “We drank.”

Brown and Yerrin combed hill and canyon but failed to find anything of value. Yerrin knew of another place. “You can have it,” Brown said. “I left a good claim.”

Yerrin eyed him a long moment, then grinned: “Stella, huh?”

The sage in Greenwater streets was rank now and again Ralph Fairbanks looked out over the dying town. “Ma, we’re getting out,” he said. He emptied his pockets on the table; counted the cash. “Ten dollars and thirty cents. Can’t get far on that—”

He was interrupted by a knock at the door. There stood a stranger who wanted dinner and lodging for the night. During the evening the guest disclosed that he was en route to his mining claim near a place called Shoshone, 38 miles south. It was near a spring with plenty of water, warm, but usable. He wanted to put 50 miners to work but first he had to find someone willing to go there and board them.

“Maybe we’d go,” Fairbanks said. “What’ll you pay for board?”

“A dollar and a half a day. Figures around $2250 a month.”

Ralph looked at Ma. She nodded. “It’s a deal,” he said.

The next morning the guest left.

Fairbanks turned to his wife. “I can haul these abandoned shacks down there in no time. Charlie’s not working, I can get him to help.”

Ralph Fairbanks had stayed with Greenwater to the bitter end. Now he hauled it away.

The road to the new site was over rough desert, gutted with dry washes. Brown slept in the brush, put the shacks up while Fairbanks went for others. Both worked night and day to get the place ready. Finally they had lodging for 50 men, a dining room, and quarters for the family. With $2250 a month they could afford a chef and Ma could take it easy. Stella could go Outside to a girl’s school.

Then like a bolt of lightning came the bad news. The Greenwater guest, they learned, was just an engaging liar, with no mine, no men. He was never heard of again.

Without a dollar they were marooned in one of the world’s most desolate areas. Stumped, Fairbanks looked at Brown. “I’ve been rich. I’ve been poor. But this is below the belt. What’ll we do?”

“I can get a job with the Borax Company,” Brown said. “But you?”

“We have that canned goods we brought to feed that liar’s hired men. I’ll figure some way to live in this God-forsaken hole.”

From the dining room, prepared for the $2250 monthly income, he lugged a table, set it outside the door facing the road. Then he went to the pantry, filled a laundry basket with the cans of pork and beans, tomatoes, corned beef, and milk brought from Greenwater. He arranged 107them on the table, wrenched a piece of shook from a packing crate and on it painted in crude letters the word, “Store.” He propped it on the table and went inside. “Ma,” he announced, “we’re in business.”

You could have hauled the entire stock and the table away in a wheelbarrow and every person in the country for 100 miles in either direction laid end to end would not have reached as far as a bush league batter could knock a baseball.

The wheelbarrow load of canned goods went to the Indians living in the brush and the prospectors camped at the spring. Another replaced it and the “store” moved then into the dining room prepared for the non-existent boarders. Powder, a must on the list of a desert store, was added. The desert man, they knew, needed only a few items but they must be good. Overalls honestly stitched. Bacon well cured. Shoes sturdily built for hard usage.

“If we sell a shoddy shirt, an inferior pick or shovel to one of our customers,” they told the wholesaler, “we will never again sell anything to him nor to any of his friends.”

Soon the prospectors were telling other prospectors they met on the trails: “Square shooters—those fellows. Speak our language....” The squaws and the bucks told other squaws and bucks. Soon new trails cut across the desert to Shoshone and soon the store outgrew the dining room in the Fairbanks residence.

From Zabriskie, now an abandoned borax town a few miles south of Shoshone, an old saloon and boarding house was cut into sections and hauled to Shoshone. It had been previously hauled from Greenwater where it had served as a labor union hall and club house. It was deposited directly across the road from the original store.

So began in 1910 an empire of trade that is almost unbelievable.

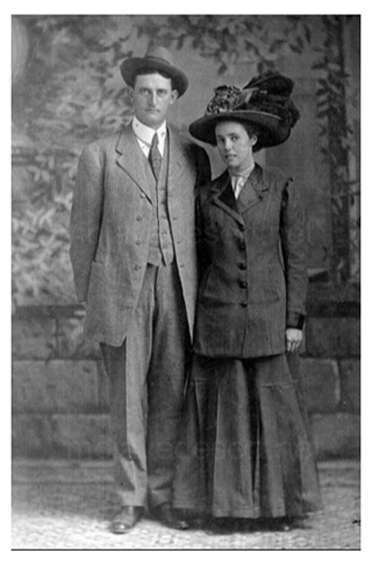

Charlie had at last coaxed the right answer from Stella but there wasn’t enough in the business at the start to support two families, plus the score of children and grandchildren of Fairbanks. At Greenwater he had known all the moguls of mining and he had only to ask for a job to get one. Retaining his interest in the Shoshone store he became superintendent of the Pacific Borax Company’s important Lila C. mine and thus formed a connection which grew into valuable friendships with the executives. The Shoshone business grew and soon required his entire time and that of Stella.

Born in Richfield, Utah, Stella Brown grew up in Death Valley country and a reel of her life would show an exciting story of triumph over life in the raw; in desolate deserts and in boom towns where bandits and bawdy women rubbed elbows with the virtuous, millionaire with crook, and caste was unknown. If a girl went wrong; if an Indian 108was starving; a widow in need—there you would find her. Some day somebody will write the inspiring story of Stella Brown.

Not all those who were told to see Charlie were seeking directions or suffering from toothache. When General Electric desperately needed talc, its agents were so advised. When Harold Ickes came out to promote President Roosevelt’s conservation ideas and officials of the War Department sought critical material, they too were given the old familiar advice and took it, and one day I saw the President of the Southern Pacific Railroad stand around for an hour while Charlie waited for a Pahrump Indian to make up his mind about a pair of overalls.

Today the store that started on a kitchen table requires a large refrigerating plant and lighting system, three large warehouses, two tunnels in a hill. About a dozen employees work in shifts from seven in the morning till ten at night, to take care of the store, cabins, and cafe. Three big trucks haul oil, gas, powder, and provisions to mines in the region. Out of canyon, dry wash, and over dunes they come for every imaginable commodity, and get it.

A millionaire city man who vacations there sat down on the slab bench beside Brown, aimlessly whittling. “Listen, Charlie,” he said. “Why don’t you get out of this desolation and move to the city where you can enjoy yourself?”

“Hell—” Charlie muttered, and went on with his whittling.

The new store stands upon the site where Ma Fairbanks’ kitchen table displayed the canned goods brought from Greenwater. Modern to the minute and air-cooled it would be a credit to any city.

Again I heard the old familiar, “See Charlie,” and while he was telling someone how to get to a place no one around had ever heard of, I glanced over the Chalfant Register, a Bishop paper, and noticed a letter it had published from a lady in Wisconsin seeking information about a brother who had gone to Greenwater more than 40 years ago. She had never heard of him since.

When Charlie joined me I called his attention to the letter. “I saw it,” he said. “Nobody answered and the editor sent the letter to me. I have just written her that the brother who came to find out what happened, died suddenly at Tonopah, only a few hours by auto from Greenwater. The other brother was killed in a saloon. I knew him and the man who killed him.”

COPYRIGHT 1951 BY WILLIAM CARUTHERS

Published by Death Valley Publishing Co.

Ontario, California

A Foretaste of Things to Come

What Caused Death Valley?

Aaron and Rosie Winters

John Searles and His Lake of Ooze

But Where Was God?

Death Valley Geology

Indians of the Area

Desert Gold. Too Many Fractions

Romance Strikes the Parson

Greenwater-Last of the Boom Towns

The Amargosa Country

A Hovel That Ought To Be a Shrine

Sex in Death Valley Country

Shoshone Country. Resting Springs

The Story of Charles Brown

Long Man, Short Man

Shorty Frank Harris

A Million Dollar Poker Game

Death Valley Scotty

Odd But Interesting Characters

Roads. Cracker Box Signs

Lost Mines. The Breyfogle and Others

Panamint City. Genial Crooks

Indian George. Legend of the Panamint

Ballarat. Ghost Town

Index

Charles Brown

Greenwater

"Dad" Fairbanks

Shoshone, Ca.