Greenwater

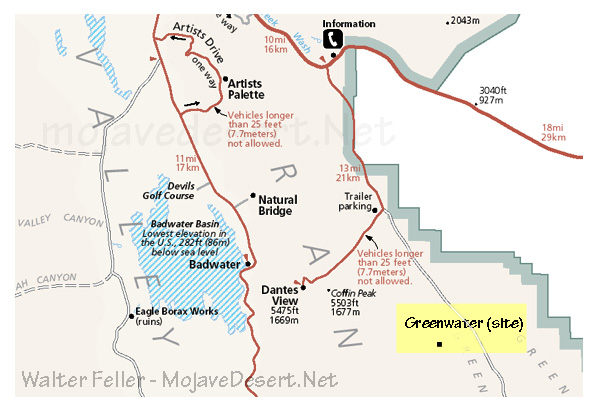

Greenwater was built around a copper strike made in 1905. Water had to be hauled into the town and was sold for $15 a barrel. The town grew to a population of 2,000 and was known for its lively magazine, The Death Valley Chuckwalla. By 1909 the mining had collapsed without ever showing a profit and people left for other areas. There are no ruins left in Greenwater, which is located south of Dante’s View off the Greenwater Valley gravel road.

source - NPS

Greenwater History

Charles Brown at Greenwater

Finding Greenwater

Squatters at Greenwater

Desert Fever - Greenwater

Also see: