Acorn Lodge - The Second Story

by Terry Graham - Wrightwood Historical SocietyIt is said that most big things start out as something small. In this case, something as small as the fragrant leaf from a California white sage started a chain of events that would lead to the creation of Camp Cajon, in Cajon Pass, and the native rock and oak structure known as Acorn lodge in Wrightwood. Camp Cajon is long gone, its unique rock work that shaped a large resting place for travelers was totally erased by the floods of March 1938. Acorn Lodge is still there, some of its uniqueness changed over time, but most of her glory exists still. They were both built by a man’s dream, spurred on by a lady who carried a simple fragrant California sage leaf. He was William Marion Bristol, she was Jennie Cook Davis.

It was in October of 1886 when a letter, sealed, stamped and postmarked from Riverside, California, reached its intended recipient in a small Westfield community in Wisconsin. The only thing that fell from its envelope was a single fragrant leaf of a California sage that had been folded inside a single page of onion paper. The leaf lazily floated to the floor, and the pleasant musty odor greeted the reader as she noticed that no note had been written thereon the onion paper. It was obviously an invitation for the Davis family to join their friends and try their luck in the west. The harsh climate of Wisconsin already gave one family member asthma, and a variety of demands had made life rather stressful. The land of warm sun could be the answer to their dreams.

The Invitation I’ve just received a letter from the home folks way out west, Sealed and stamped and postmarked, and properly addressed... There’s not a word of greeting upon the folded page, But from it fell a fragrant leaf of California sage! They’ve coaxed and begged and argued, but I’d always some excuse... I told them I was anchored that talking was no use. And now that I’ve convinced that it is futile to resist, They’ve sent this invitation that they know I can’t resist! Well. I’ve earned a good vacation, I’m checking out today, To-morrow I’ll be speeding west Upon the Sante Fe. (Written by J.C. (Jennie Cook) Davis 1887)The family packed for the train that would take them across the wide plains, Herbert and Jennie Cook Davis, along with their two daughters, soon were on their way to the West Coast. Over time Jennie Cook Davis, who was thrust forward to a new destiny by a single sage leaf, would become a thriving writer and artist. Earlier trips west, and then back home east again, left lasting memories. Looking out of her railroad car window at the vastness of the prairie, Jennie could see the trails that settlers took to seek new beginnings into the west. Bleached white bones of cattle and oxen lay scattered on prairie grass, while faded and weathered and broken discarded wagons were here and there, their torn canvas flapping loudly in the winds. Burned out husk of farm wagons and human bones ravaged by turkey vultures, wolves and coyotes, were sometimes seen. All were evidence of Indian massacres and just poor luck trying to fight nature’s harsh rules. It was the price sometimes paid when looking for the promised land.

Jennie Cook Davis began writing of the spirit of such pioneers and their plight across the unforgiving land to a place that had more promise, and a place to start life anew. One such poem was called “The Overland Trail”, and like other of her writings, it found its way into New York magazines and newspaper and to readers nationwide. Jennie Cook Davis had been a reporter on New York and Milwaukee papers, the Overland Trail poem was first written in wildwood magazine and later in Santa Fe Magazine.

In 1896, Jennie and her husband, Herbert, arrived in California for good. Summoned by that single California white sage leaf. With some trials along the way, the family would finally make route in present day Devore in 1917, when her husband became the agent for the Sante Fe Railroad at the Devore Station. Unknown to her, she will soon have an encounter with a die hard dreamer that lived miles to the east of her on an orange ranch.

William Marion Bristol was considered to be inventive and energetic. Born in Belvedere, Illinois January 20, 1859, he ended up in Los Angeles, California selling real estate, only to lose what fortune he had in 1887. Never one to lose hope and drive, Bristol packed up his two burros, Samson and Moses, and went out to seek fame and fortune in the California country side of the Sierra Madre Mountains and in the San Bernardino area.

In three years, Mr. Bristol was able to stake a homestead claim in East Highland, and he later bought additional acreage and his property was called the Way-up Ranch. After a well was drilled, the ranch was well above the frost line, on Harrison Mountain in San Bernardino and water was never a problem. The ranch was ideal for growing oranges and soon Bristol was on his way to another endeavor of being an orange grower. It was during this time that Mr. Bristol began shaping a relationship with the founders of the Southern California Fruit Exchange.

The SCFE was formed in 1893 in Claremont by P.J. Dreher and his son, the "father" of the California citrus industry, Edward L. Dreher (1877-1964). The exchange soon included growers and groves in Pomona, Riverside and San Dimas in Los Angeles County, and Santa Paula, Saticoy, Fillmore and Piru in Ventura County; by 1905, the group represented 5,000 members, 45% of the California citrus industry, and renamed itself the California Fruit Growers Exchange in 1905. It adopted the "Sunkist" name in 1908 for its highest quality oranges, and so was the first to brand fruit. During this time period, many of the individual orange crop growers were allowed to design and use their own 'Sunkist' labels to represent the Sunkist Company. Mr. Bristol was one who designed his own label, which he used on his products. He also invented the household manual orange juicer, which was patented after the lemon jucier and was used as promotional gimmick for Sunkist.

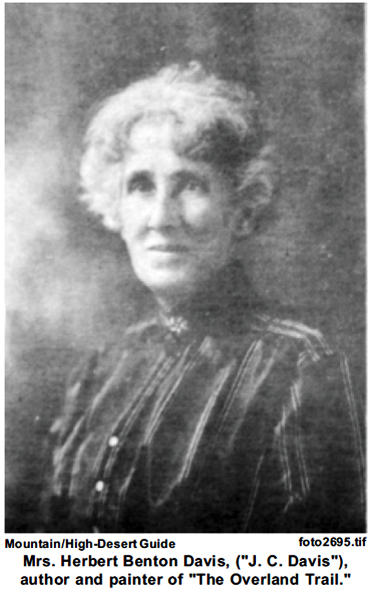

Soon, Mr. Bristol would be married to Fannie Howe Dearborn, have four children (and dealing with the pain of losing two of them), and become very active in the community. During the time rising crops on the Way-Up Ranch, Bristol became enthraled with the writings and poems of J. C. Davis in The San Bernardino Star. J. C. Davis was the masculine name for Mrs. Herbert Benton Davis (Jennie Cook Davis). The writings and poems were of the opening of the west, and because of that, Bristol’s interest was peeked,. With his tanned rough work hands, he habitually cut out her articles and saved them. Through her writings, Bristol once again got the wandering lust and he began roaming the areas that his wife, Fannie, did not want to go. His wife was involved with life on the ranch and social functions in San Bernardino, she had no interest in William's pursuits in exploring the nearby Sierra Madre Mountains, most specifically the Cajon Pass area.

On Dec. 23, 1917, the pioneers' Society of San Bernardino dedicated a monument that they had built to mark the Salt Lake and Santa Fe branches of the old Spanish trail. William Bristol got an invite to the ceremony, at the same time he got a heck of an idea. He learned that his favorite writer, Jennie Cook Davis, who was now a widow, lived in the area at the Devore Sante Fe Railroad station. It would be fitting that the author of the poem, “The Overland Trail”, which dealt with pioneers entering the land, should be present at a dedication that saluted those pioneers. To show his special interest in Jennie’s work and to involve her in this project, he picked her up from her home in Devore and took her to the dedication.

Following the oration of the day by Federal Judge Benjamin F. Bledsoe, Bristol read the poem, which was well accepted by the crowds. He led Jennie to the stage, where she received a tremendous applause for her writings.

Jennie Cook Davis , J.C. Davis’ collection of poems did not sell well, the public recognition of Jennie, the artist, was still yet to come. Bristol was a business man, a prosperous orange grower in Highland, and an aspiring writer in his own right. He was always interested in new ventures which might be profitable. But, at the same time, he had a romantic streak in him and her first major tribute for her writings came from him. The following stanza from “The Overland Trail” was carved into a large boulder at the entrance to Camp Cajon:

"Over the sage-brush desert gray

Through alkali patches pale,

It stretches away and away and away-

The weary overland trail."

The San Bernardino Daily Sun referred to the role of Jennie Cook Davis’ poem in the Cajon Pass venture and Bristol’s selection of the poem as ‘being the most appropriate for the gateway of southern California. Not long afterward, Bristol made a radio broadcast called "Radio Story of the Poet of Cajon". Bristol was called the "father of Camp Cajon" and Jennie the poet laureate of the desert." Mrs. Davis might have gained an admirer in her work, but she starting to see another side of William Bristol. It appeared that Bristol was using her talents to help promote his own ambitious goals.

(The Life Story of Jennie Cook Davis, by Karin Neset Smith, pp. 186. 1995)

Two years later, in May of 1919, William M. Bristol pitched a tent in the scrub oak, pine and sycamore trees in Cajon Pass. Over the years, Mr. Bristol had also become an accomplished writer. In those writings he commented that the only reason why he ventured into the area was because of J. C. Davis writings on settlers coming west. Cajon Pass was an unique place for Bristol to camp and reflect on those things. Less than seventy years before, many settlers came through the area of Cajon Pass and began building settlements in southern California. Those many travelers came up the Spanish Trail...which ended in Cajon Pass, and it became one of the major doorways that opened the west. Captivated by the area, Bristol envisioned a place where weary travelers can rest and relax. Before long, the dreamer would built that place. The story of William Bristol, the man who built Camp Cajon is told in the book ”Trails and Tales of the Cajon Pass: The Man Who Built Camp Cajon”, written by John and Sandy Hockaday, Buckhorn Publishing-

William Bristol’s next idea would also include Jennie Davis, it was the construction of an expensive mountain home on the northern slope of the Sierra Madre Mountains (present day San Gabriel Mt.) at Wrightwood, Ca.. In The San Bernardino Leader March 12, 1931 issue, it described "The House that B...Built". It was called Acorn Lodge and was intended to be a "museum of nature. Built of local stones and wood, it was described as having natural and historical features.

Seven years passed by since the creation of Camp Cajon, when in 1926, Bristol's attention was driven deeper into the surrounding mountains and he found himself 12 miles further northwest in the small community of Wrightwood. On the southwest corner of what would be called "Spruce Street and Eagle", he began building on a block long area, which he purchased from Sumner and Kate Wright in 1926, an unique structure of native rock and wood.

Acorn Lodge was built within a small grove of towering oak trees. It was built of oak logs set on end on top of a massive stone foundation that rose to the bottom of the lodge windows. At the corners of the living room, the corner logs flanked the wide fireplace,. All the corner logs were three feet in diameter and hollowed, and the hollow portion of the logs face inward. The two hollowed logs on the west wall were unique, for each had a different local landscape scene painted on light weight galvanized iron. One was of Mount Baden Powell and one of Wrightwood's lakes surrounded by large pines. The thin wire grates that fit over the painted vertical openings, in conjunction with the illuminating lights over head, makes you feel that you are looking out a typical window at a perfect outdoor scene.

Jennie Cook Davis painted these scenes under the strong urging from William Bristol, but he was not done utilizing her gifts. "Now I want you to make a series of paintings to illustrate your poem of the Overland Trail." Jennie did not want to and protested...but she yielded to Bristol's incessancy. At the age of 77, she painted the scenes of the Overland Trail, and in a short while, William Bristol would be building the present day Overland Trail building at Acorn Lodge to show off her work.

Jennie wrote the poem "The Overland Trail" forty-three years previously...now she would be painting the scenes of the poem by memory. The painting of Jennie Cook Davis were ten in all, each were approximately six feet by four feet, and each of them illustrated stanzas of the poem. Mrs. Davis paintings included a team of oxen and wagon coming down a ridge towards water, an Indian with an Indian pony and bison on a rise, a burning covered wagon, a view of covered wagons in a small valley from a ridge and a lone coyote. While she painted, Bristol also worked.

The Overland Trail building was built to house the panoramas painted by Jennie Cook Davis. It was approximately twenty feet by fifty feet in dimensions and constructed out of the granite and white rock from Wrightwood's many canyons. The building's eight columns of white quartz came from a giant boulder...as did the bronze-colored rock border around "The Overland Trail" mosaic on the face of the north exterior way. The rock used to form “The Overland Trail” came from the same rocks that were used in the earlier construction of Camp Cajon, in Cajon Pass.

With an electric pencil, Mr. Bristol etched each stanza of Jennie Cook Davis' poem "The Overland Trail" on small pine rounds. He shaped a group of alcoves out of logs set on their end and that reached up to the base of each painting. Painstakingly, Mr. Bristol used stone, sand and desert vegetation to complete the three foot by one half foot deep alcoves. He then shaped a landscape in the foreground of each alcove to match the painted scenes. On each alcove, Bristol attached the pine rounds that had each stanza etched into it.

Mrs. Herbert Davis (Jennie Cook Davis) was modest about her “Overland Trail” paintings, but they soon attracted the attention of many people. For a time, the paintings hung in the Harris Company windows in San Bernardino to promote the existence of Acorn Lodge.

Jennie Cook Davis’ writings suggested that she felt that William Bristol was using her gifts to further his own notoriety. Bristol had begun charging twenty five cents per person for the tour of Acorn Lodge, including the beautiful “Overland Trail” museum. In addition, he wrote and published “The House that B...Built”and sold it to tourists for one dollar a piece. The book, which detailed the makings of Acorn Lodge, gave notice to Jennie Cook Davis and her art. However, instead of allowing her to have copies of his writing, he imposed the price of the book on her! Despite Mr. Bristol building her the “Overland Trail” to showcase her work and also allowing her quarters in the Acorn Lodge, she felt that she did not get proper contributions for her work. The money that Mr. B collected for the book and tour of the “Overland Trail” museum was never shared with her! But the writer believes that ample contribution was given for her great work. During her lifetime, Jeannie Cook Davis would gain more fame under her own merit.

Jennie Cook Davis returned to Acorn Lodge a year following William Bristol’s death, to find her showcase still intact and the Lodge’s new owners very friendly and courteous. The “Overland Trail” was locked, and due to the Sutherland’s being out of town, she was unable to see her work that was inside the “Overland Trail”. She was surprised to see that not much of the Acorn Lodge had changed, even her room in the “Sycamore Room” was still set aside from the other rooms. Mrs. Herbert Davis (Jeannie Cook Davis) left the lodge for the last time with a happy heart. Caretaker James Cairns offered her over thirty copies of “The House that B—Built”, something that Mr. Bristol tried to sell her years ago.

William Marion Bristol, Mr. B—, worked on the construction of Acorn Lodge for three years. Hampered by a left hand that had been seriously injured years ago while working at his “Way Up” ranch in East Highland, he was able to build the main lodge, a back storage room of rock and stone, a one car garage and the nearby “Overland Trail” museum. Local Forest Rangers, including J. Buford Wright, the nephew of Sumner Wright, assisted in standing giant black oak logs on end to fashion the sturdy foundation of Acorn Lodge. Painstakingly, Mr. Bristol mixed white rock with native granite to form a pattern into the large road foundation and the adjacent garage and “Overland Trail”. With pieces of actonolite to shape a decorative acorn on the upper portion of his chimney, these words he fashioned out in white rock on the chimney’s front: Acorn Lodge 1926.

With native boulders taken from local creek beds, Bristol built twin five foot rock towers to form a doorway that led into the Lodge property. A fifteen inch diameter curved oak branch formed an arch that connected both towers, it allowed people to walk through and read the greeting etched and painted upon that arch overhead; “All care abandon ye who enter here”. In time the wooden arch became fractured by the weather and taken down. By 1962 it no longer existed.

Built of a spiral shaped limb, Mr. B— fashioned a turnstile that stood at the east steps of the large north facing rock porch. One end of the limb sat in a sunken pipe embedded into one stone step. A bevel was cut in it and the stile automatically returned to a closed position, waiting for the next person to walk through it. The turnstile was later moved to the previously mentioned front entrance arch. Even though it no longer exist, the turnstile pieces were stored against the north exterior wall of the main lodge through the 1960's...wood stained and polished.

A five foot hollow seat made of pine log rounds once sat under the present day Honeymoon Cabin, it was big enough to provide a comfortable seat to allow a person to get out of the sun’s glare. But like all wood, the rounds fell apart over time. They were still there in the 1960's, but in many pieces.

On the east end of the massive front porch once sat a large eight foot high acorn brush wickiup fashioned with slender willow switches. It was big enough for someone to sit comfortably inside of. Over time, it too fell apart...it lasted until around WWII, and its decay was complete in 1952. It became one of the items discarded and burned when Church of the Open Door bought the property for camp retreats.

The 30 foot oak wooden flag pole that once graced a newly constructed Acorn Lodge was later replaced by a sturdier metal one. The first pole was planted with the help of six rangers, including J. Buford Wright.

The north front porch of the Acorn Lodge still supports many of Bristol’s creations. The two seven foot bell towers still have granite rock shaped into soundless bells, supported by lengths of chain. The towers themselves are outlined with white rocks in shape of bigger bells. The porch, which was called the terrace, was wide and long...at the door was a cedar slab with the words “Acorn Lodge” uniquely spelled out in bored out holes filled with old acorns. The shake-roofed cedar seat, which was big enough to hold six people is long gone. Another wood structure fallen victim to time and weather. In 1963 it was barely holding together, so it was finally dismantled and carted away.

On the south side of the terrace, nestled between a wide branching towering oak, was a large swing made of thick oak branch that was suspended by a pair of thick metal chains. Across the way was another large oak swing. The wood faded with weather, it is still strong enough and comfortable enough to sit under the green leaves of spring and summer and the golden falling leaves of winter. Between railings of thick oak and towing granite walls sits the Acorn Lighthouse. Still a beacon, powered by a pair of light bulbs inside her. The acorn mold was cast by Bristol, himself. The electric light was dropped down through a small chimney at the peak of the stone shingle roof. To the east of the lighthouse was the white rock and dark granite stone sundial. The top was separated by white rock for day and dark rock for the night...a crescent moon and north star stood out against the dark rock (sky). “I count none but sunny hours...”

Inside the east door way of the Acorn Lodge main house once hung Banshee the Irish Ghost. His face was fashioned from a split knot in the wood. Bristol used red cedar bark for its nose and pine needles for the hair, while acorns for the eyes completed the ghost’s appearance. Over time the appearance faded, the only thing that was left what the natural split knot.

Outside and in the south yard was said to be the largest ox cart in Wrightwood. With a cart tongue made of a small pine tree, wheels of pine rounds...and a bed of hard wood, the ox and ox cart was long gone before the 1950's.

The garage that B—Built was made of stone and oak, the decorative white stone wheel still stands out today. It was big enough for one vehicle. The right front had a sliding door that gave access to its interior. The left side Mr. Bristol used for his living quarters in his later years. It became his resting place as he climbed into his pine planked and cedar fashioned casket fulled of oak leaves and took his own life. In the middle 1950's it was made into a craft room. A single door and a set of windows took place of the garage doors as a cement patio was put in between the white rock wheel and the new garage front. In the 1960's it was used as a snack house and craft room.

Acorn Lodge’s front door itself was one of a kind. Above its frame were two eight foot long arrows made of straight branch wood. Legend had it that the two giant arrows were shot into the forest and they brought down the two hearts that were mounted behind them. The Entrance of the Lodge, located on the north side, was made of a thick central oak slab ripped from a stump and framed in black oak. The door itself weighted 600 pounds and was 5 1/2 feet wide and 7 feet tall! A central ball bearing allowed it to turn easy and noiselessly. But first things first...you had to ring the chimes. “The quest may ring that the host may know he has come to the House that B-built.”

There were five tubular chimes, one and one half inch in diameter and six feet long, that once hung in a nook just inside the front entrance. They were electrically connected with a keypad outside the door and under a thick patch of oak bark. Pulling the latch string on the adjacent oak door frame activated the chime. The same chimes sounded when the hours and quarter hours of the large fireplace clock hit the proper time. Over time, the chimes were taken off the wall. Bits and pieces of the tubular chimes were discarded against a back wall and by the 1960's, the only thing remaining was a small electric box still attached near the front entrance and electrical wiring on a rear bathroom wall. The carriage lamps that graced the front entrance, as well as the east entrance, remained through the early 1960's. But they soon became inoperative, then impracticable... and then they were finally removed.

Inside the lodge Mr. Bristol had posted the famous bleached white steer bones called the “Skull and Crussbones”. The skull and crossbones were attached to a burnt piece of hollowed out oak bark near a ceiling Joyce adjacent to the entrance of the living room. Right next store to a three foot diameter, seven foot tall tree trunk The pine tree trunk was without rhyme of reason, except for a limb closely resembling an uplifted arm and hand. It looked strangely like a person taking an oath in a court of law. “Do you swear to tell the truth and nothin’ but the truth, so help you God?” ...”Yeah, up to a point..”...”What point is that?”...”To the point where I start lying.” The oath doesn’t sound out of the ordinary, considering the fact that Mr. B-was a practical joker as much as he was a reader and creator.

Ahead into the livingroom was the big bold fireplace. Its keystone spangled with bronze and gold. Half of the stone was beautiful gray schist, the other portion was more of a reddish color, both were mates from a flat slab from a boulder split by Bristol’s own hands. At either side of the great clock hung long dark panels that bore the Shakespearian quotation “Come what, Come may, Time and the Hour Run thru the Roughest Day-MacBeth...” Even though the bold fireplace still stands as it did at its creation, Macbeth’s statement is long gone...way before 1963. The clock above the great fireplace mantle still attracts the eye. The housing of the clock is of green actinolite, its face is of white quartz embedded in white lacquer on a metal base. It’s letter, architectural Roman, are made of metal and coated with green actinolite. The clock was electrically connected and sounded off the hours and quarter hours. In the 1960's it kept good time...the question is does it still keep eternal time in the present years?

At the corners of the living room, corner logs flanked the wide fireplace,. All the corner logs were three feet in diameter and hollowed, and the hollow portion of the logs face inward. The two hollowed logs on the west wall were unique, for each had a different local landscape scene painted on light weight galvanized iron. One was of Mount Baden Powell and one of Wrightwood's lakes surrounded by large pines. The thin wire grates that fit over the painted vertical openings, in conjunction with the illuminating lights over head, makes you feel that you are looking out a typical window at a perfect outdoor scene. Jennie Cook Davis painted these scenes under the strong urging from William Bristol.

The kitchen was non descriptive, but the dinning room area was filled with odds and ends of tables fashioned from pine rounds and legs made of sturdy oak. One table was large enough to sit a dozen quests with a raised serving rotating section made of a pine round in the middle. This large table late sat in the garage when it became a craft room.

Knickknacks of ceramic acorn shaped salt shakers and napkin holders were placed on the large dinning room table, while a large mirror framed in oak graced the wall behind them. Chairs were made of sturdy branch wood and small acorns hung from chains that were connected to the overhead electric lights. The unique dining set lasted until 1951, when the second owner, Dr. Samuel Sutherland, sold the Acorn Lodge to the Church of the Open Door. Even though the Lodge was used for church groups and retreats during Mr. Sutherland’s time, he enjoyed art and the unique knickknacks that Mr. Bristol had created. He kept the Lodge and “Overland Trail” museum as original as possible. On an interior wall once hung “The Harp”. Framed by heavy Ponderosa Pine bark was a large weathered root of a lodge-pole pine that had been dislodged from a ledge of rock during road construction. Approximately three and a half feet high, it tapered from three feet wide to a foot wide in an actual shape of a harp. Thin gauged wire served as its strings. It was long gone from the Lodge prior to 1962, problem carted off by a music lover. Also missing was a bark framed art design of two turtle shaped white-oak stumps, one turtle following the other. “Hale and hearty and round and plump, they stayed in the House that B-Built”. The heavy piece of art leaned against the wall under a oak shelf that supported a lamp with a large acorn base. The last resting place of the turtles is not known. Hung on the south interior wall of the main room was a pine stump saved from flame, it resembled the head of a Big Horn Mountain Sheep. This piece is too long gone, perhaps meeting its first destiny of feeding a hungry fire.

At the time that Acorn Lodge was built, and until approximately 1952, it had four bedrooms, two on the north side and two on the south...divided by a long hallway that went from the east entry door to the main room. Each of the rooms had their own themes. The Oak Room was identified by its great animal shaped black oak headboards and bedframes, and graced by ceramic acorns at its footboard. The headboard look strangely like and elephant’s trunk with a set of ivory tucks. This was the northwest bedroom. The northeast bedroom was “The Arrow Room” and was identified by its large oak corner stand with a large ceramic arrowhead in its middle. It was accompanied by Longfellow’s “I shot an arrow into the air” poem etched on small pine rounds by Mr. Bristol. The bedroom had a heavy cherry wood bedframe and headboard. The Southeast bedroom was called the “Acorn Room and it was identified by its heavy oak corner piece with a mirror and oak bark frame shaped like an acorn. The bedframe was of oak and the headboard and footboard was nicely curved. This bed, and the heavy cherry wood bed in the “Arrow Room”, were still in the lodge through the early 1960's. The southwest bedroom was called the “Sycamore Room”, and it was identified by the large oak tree seen in the south yard as you opened the drapes and looked out the window. Even though there is no photo of this fourth room, it is speculated that this particular room was the one set aside for Mr. Bristol’s friend, artist and writer Jeannie Cook Davis.

The Honeymoon Cabin, raised up seven feet and support by the thick limbs of a spreading black oak, was made of pine, cedar and oak. A single room with broad windows, it contained a single comfortable bed, a few pine rounds night stands and a oak framed dresser and drawers. On its wall were plaques of the names of just-married people who shared the quiet time alone. Their privacy was complete...access to its borders were the wooden steps attached to the rear roof of the adjacent wood and rock storage room. The only way to reach the Honeymoon Cabin was a makeshift drawbridge. Untie and pull the rope, the bridge extension lowers to the wooden steps. Carrying the new bride up the rickety wooden steps might had been a chore, but it was well worth the effort. Once the happy couple reach the threshold of the Honeymoon Cabin, the rope was pulled again and the drawbridge retracted. Separation from the interruption of the outside word was complete. At least for the time being.

In 1952, the third owners of Acorn Lodge, the Church of the Open Door, tore down two of the bedrooms to expand the main room to allow for more quests. At the same time, the Overland trail” museum was made into a woman’s dormitory. Meanwhile, in 1953, the pool and adjacent pool house was put in under the guidance of caretaker Les Williams.

The construction and details of the “Overland Trail” were discussed in the first chapter of this humble account of Acorn Lodge. It is important to mention that previous owner Dr. Samuel Sutherland told the new owners that the art remain intact but displayed in the hallway of Acorn Lodge’s main house. During the remodeling of the “overland trail”, the barriers and alcoves protecting the paintings of Jeannie Davis were torn down and discarded. Local history makes record that a “bonfire” destroyed much of the artifacts within the main house and the “Overland Trail”. Yet three separate paintings of Jeanne Cook Davis hung in the hallway of the Lodge through the 1960's. These paintings were seen by five separate families who had been interviewed about Acorn Lodge The painting scenes included a lone Indian warrior on horseback on a ridge, a lone howling coyote and a wagon with a team of oxen coming down a slope into a river. Between 1967-1985, these paintings disappeared from the hallway of Acorn Lodge, as did many pieces of knickknacks that Mr. Bristol fashioned. Their whereabouts are still unknown. One sole survivor of Jeannie Cook Davis’ paintings currently hangs in the Wrightwood museum. It was donated by the graceful local historian Pat Krig.

The Church Open Door did have a bonfire to burn piles of debris and trash. The reader must understand that most of the unique art created by Mr. B-was of wood. Over time, wood splits and decays. It would be understandable to discard such material. But what of the art that apparently never made it to a hanging hook in the main house? Six of the ten Jeannie Cook Davis paintings remained unaccountable for in 1952. By the present day only one remains. As a child growing up, the author remembers that at least two beds and three dresser and drawers framed with oak were still inside the Lodge, as were a number of tables made of pine rounds and ceramic acorns.

By 1985, the unique wood knickknacks, tables and bedframes and other odds and ends that gave Acorn Lodge its character, were long gone. No doubt most were discarded by necessity. Acorn Lodge still retains her glory on the outside, not to mention her bold fireplace and clock on the inside. Times change, they say, but the mountain stays the same. Acorn Lodge still rests quietly in a small grove of oak. As each season passes, a person is still drawn to a place between contentment and daydream. May it always be so.

-END-

Inside the Wrightwood Museum, for your viewing pleasure, is the narrative and photographic history of Acorn Lodge. There are still many questions that need to be answered concerning Acorn Lodge. That's where the Wrighwood longtimers come in. Your input is needed to complete the picture of the life and times at Acorn Lodge.

Humbly submitted,

Terry Graham, WW