Boom Days in Old La Paz

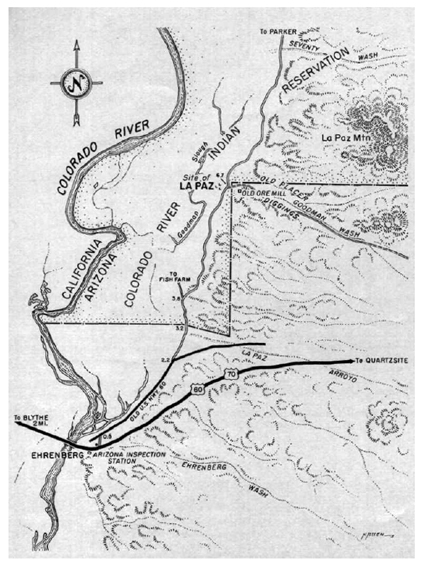

By AUDREY MAC HUNTER and RANDALL HENDERSONMap by Norton Allen - Desert Magazine

ONE JANUARY day in 1861, Capt. Pauline Weaver, colorful Mountain Man of the mid-1800s, arrived in the little settlement of Yuma on the lower Colorado River and exhibited nuggets of gold found by himself and his companions 70 miles upstream wheie they had established a camp for their beaver-trapping operations.

The word quickly spread—a gold strike along the Colorado River. Don Jose Redondo heard Weaver's story and at once set out with others to verify the report, and explore the area. Reaching the Weaver camp members of the party spread out with gold pans and what water they could carry to prospect the area. Less than a mile south of Weaver's camp Redondo washed a single pan of gravel that yielded more than two ounces in small particles of gold.

A good showing of color also was found by other members of the party. Since they had not come prepared for extensive operations they returned to La Laguna, a settlement 20 miles upstream from Yuma, to obtain equipment and supplies.

News of their discoveries was carried by stage and freight drivers to San Bernardino and the coast, and in February, 1862, 40 gold-seekers arrived at the new placer strike. The placer field was named La Paz, adobe buildings soon were under construction on the shore of the river which became a port for boats operating between Yuma and the placer field.

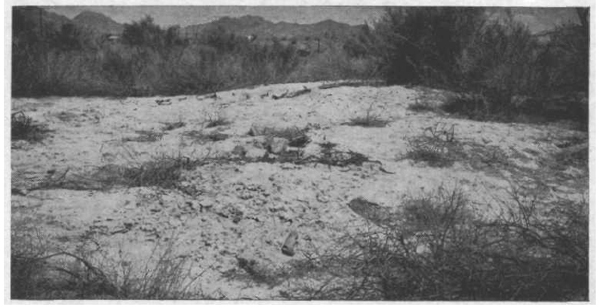

Where the old adobe walls of La Paz melted away when the river overflowed in the mining camp site in 1912.

Millions in gold nuggets were taken from the gravel at La Paz during its boom days nearly a century ago. Today the site of the old camp is overgrown with mesquite and arrowweed, but the ghost camp may come to life again—as a trading center for the rich farm lands owned by the Indians on the Colorado River reservation.

Discoveries were made almost daily until news spread that every gulch and ravine for 20 miles south and east was rich with gold. Ferra Camp, Campo en Medio, American Camp, Lo Chollos, La Plomosa, and many smaller places, all had rich diggings. But Ferra Gulch probably was the most valuable of all. News of these discoveries soon spread to Sonora and California and the rush was on until there were probably 1500 prospecting for the fabulous gold.

This number remained until Spring of 1864 when the apparent exhaustion of the placers and the extreme high prices charged for provisions caused many to leave. Most of the miners left anyway during the extreme heat of summer. Considering that the standard wages of the country at this time were $30 to $65 a month with board, the miners were doing well working the mines. It was often said of that day that "not even a Papago Indian would work for less than $10 a day."

Regarding the yield of the placers, it was common for a man to take more than $100 in a single day, and it is said that occasionally the day's work yielded nuggets worth $1000. Don Juan. Ferra took one nugget from his claim which weighed 47 ounces. Another party found a "chipsa" that weighed 27 ounces, and another one of 26 ounces. The contention was that a good many of the larger nuggets were never shown for fear of evil spirits that the superstitious miners felt haunted the mines. The gold was large and generally free of foreign substance. The 47-ounce nugget did not appear to have any quartz or other foreign matter. The gold did vary a little as to its worth at the mint in San Francisco, bringing $17.50 to $19.50 per ounce. However that which was sold or taken at the mines went for $16 to $17 per ounce. It was estimated that at least $1 million was taken from these diggings during that first year, and probably as much more was taken out in the following years.

As evidence that the La Paz strikes were rich and money plentiful, prospectors were known to pay as much as two dollars a gallon for water to drink or to wash gold. This seems incredible that water could be so precious with the ofttimes rampaging Colorado at their doorsteps. But the river water was muddy and men crazed with gold had no time for digging wells.

Now as to La Paz itself. In Spanish, the name means "the peace," probably named so because the gold was supposed to have been found on January 12, the Feast Day of Our Lady of Peace. Yet the town that sprang up as a trading center for the miners was anything but peaceful—few mining towns were, in those days of free money and fevered excitement.

Within a year there were probably 5,000 people living in La Paz. As in most early day mining camps, gold was rated higher than human life by the gangs of outlaws who invariably infest boom towns, preying like vultures upon the riches of the land.

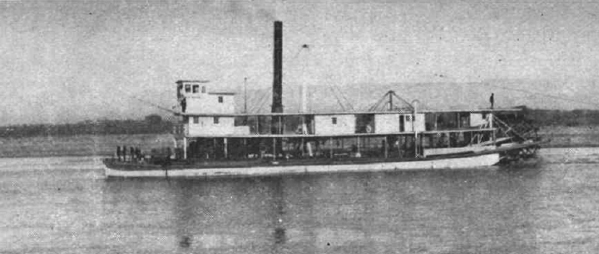

There was no scarcity of saloons here although whisky, the chief beverage, was expensive. Freight rates were high; only the most potent liquor seemed worth the price to import. The river boats did a thriving business bringing in supplies from San Francisco by way of Guaymas, and carrying the gold out.

At this time the eastern half of the United States was occupied with the Civil War, but in the mining camps, the men were content to pan gold and ignore the war. Instead of shipping their gold east, they sent it by boat down the gulf to Sinaloa, Mexico, to be milled and sold.

Most of the camps of Arizona Territory— Wickenburg, Signal, Prescott, and others, depended on freighters to bring in supplies from the river landing at La Paz. Until the establishment of a military post at La Paz, the Indians had been waylaying these shipments with a heavy toll of life and supplies. If a supply train was too big to safety annihilate, the Indians would bargain, taking one of the wagons in exchange for safe passage. It was suicide for a freighter to take to the trail alone. The army even tried to out-maneuver the Indians by hiring their leaders as scouts or guides, but the plunderings and massacres continued.

One day the commanding officer at La Paz called in a chieftain of the Mojaves, and asked why the Indians did not settle down and live peaceably. The officer pointed out the advantages of a life of hunting and ease. The chieftain seemed not at all impressed. "Do not white man like to hunt quail and deer?" he asked.

The officer admitted this to be true.

"Indian like to hunt white man," replied the chieftain with finality.

All through the Civil War La Paz was one of the most important towns of the territory. At one time it missed by only one vote of being named the capital city of the Arizona Territorial Government. It was, however, the county seat of Yuma County until 1870 when the citizens of Arizona City (later Yuma) were able to outvote the citizenry of the mining camp and move the county offices down the river.

Among those who contributed to the history of La Paz and the territory was Captain Polhamus who operated river boats for 40 years on the Colorado. This colorful skipper told of carrying fabulous shipments of gold down the river on his boats. Sometimes as much as $100,000 in gold dust was cached away in bunk mattresses to protect it from the outlaw element who worked the river. Some of those who made history at La Paz lived to cast their lots with Tombstone's lusty existence. Ed Schieffelin is said to have met with his brother, Dick Gard, and O'Gorman here at La Paz to make plans to work the famed silver claim at Tombstone.

Most mining camps live only as long as the minerals are there and a market exists. The life of La Paz was cut short more by the wiles of a river than by the law of supply and demand. In 1870 the Colorado River, in one of her temperamental moods, changed her course and left La Paz stranded two miles away. A river town without a river or a landing cannot long remain a town. Too, when the most promising cropping of gold had been winnowed from the gulches and hills, men began turning their faces toward new horizons. As always where adventurous men gather, there are stories of fabulous strikes waiting for them in the next county or state.

By 1875, when Thomas Blythe had undertaken the reclamation of 40,000 acres in the Palo Verde Valley across the river, the town of La Paz had been abandoned. The adobe walls of the old mining camp . were still standing in 1911 when the U.S. Land Office made a survey which established the boundaries of the Colorado River Indian Reservation adjacent to La Paz. However, in June, 1912, when a record flood discharge came down the Colorado River from its Rocky Mountain watershed, the water overflowed the townsite and the adobes melted to the ground. Today the site is so overgrown with mesquite and arrowweeds that it is difficult to identify the exact location of old La Paz.

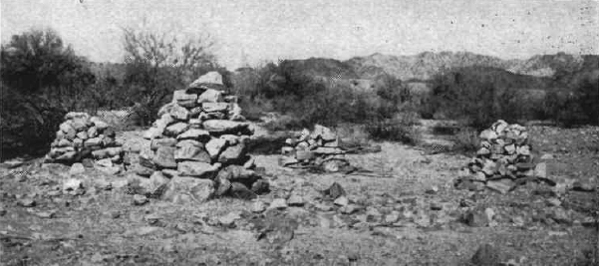

The crude equipment used by the prospectors of the 1860s did not do a clean job of recovering the placer gold in La Paz, and anyone with a gold pan and sufficient interest may get a showing of color in any of the arroyos which once yielded a fortune in nuggets. In 1910 a mining man, O, L. Grimsley, sunk numerous test holes in the gravel and decided that the area could be worked profitably with a dredger type of operation. He formed a company and raised sufficient capital to build a large stone reservoir on a hill overlooking Goodman Wash. His plan was to pump water from the river and bring in a hydraulic dredge. However, Grimsley was killed in an auto accident soon after the reservoir was constructed, and the plan was never carried out.

During the depression days of the early 1930s when millions were unemployed, prospectors who knew about the La Paz placer field returned there with dry washers and many of them recovered enough gold from the gravel to keep themselves in grub. One of these depression prospectors is said to have found a $900 nugget which had been overlooked by the old - time miners.

More recently a mill has been erected at the edge of the mesa near the old La Paz townsite, but its operation was discontinued after a few months. (circa 1958)

Goodman Wash and the surrounding area is dotted with the cairns of prospectors who have relocated much of the old placer ground, but at the present time there is little activity in the field.

While the gold of old La Paz has been mostly taken out, the Indians on the adjacent lands of the Colorado River Indian Reservation have discovered that their fertile river bottom lands will produce untold wealth in alfalfa and cotton and vegetable crops —and there is the possibility that before many years a location near the lost ghost townsite of La Paz will be selected for a permanent trading center to serve the needs of a rich agricultural industry.

Desert Magazine -- September, 1958