Dale

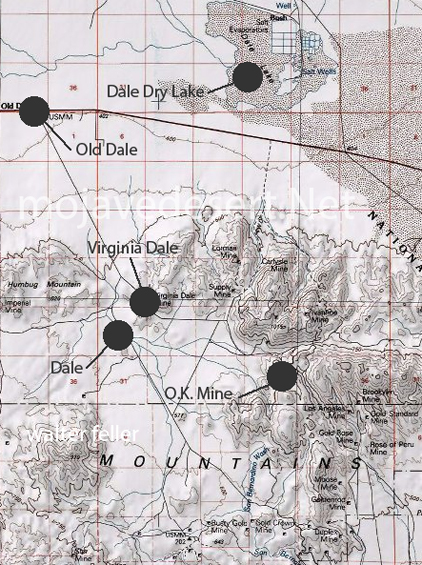

WHEN THE VETERAN TRAVELER J. Smeaton Chase stopped at a mine in the Dale district in 1915, he looked at the precarious lifeline that connected the district to the nearest railroad, at Amboy: The view to the north was memorable as an example of the ultra-desolate. Beyond the ragged brown foreground lay the pale gray expanse of a dry lake, whitened near its centre by the alkaline deposit from its vanished water. Beyond that rose the ashy wall of the Sheephole Mountains, quite lunar in their look of geologic age and dreariness. A thread-like line that skirted the lake bed and faded in a gap of the hills marked the road to Amboy.Who would dare to mine in such an area? An untold number of hardy loners and sophisticated investors from the cities of California. Within miles of Chase, who was staying at the Supply Mine, were half a dozen producing mines and a dozen or two that occasionally made news. The earliest history of the district is murky. The Virginia Dale Mine was discovered in 1885, reportedly by Tom B. Lyons and Johnny (alias Quartz) Wilson. The claim lay about 35 miles south of Cadiz, a station on the Santa Fe line, and near a dry lake named after prospector John Burt (since renamed Dale Lake). Lyons and Wilson organized the Virginia Dale Mining Company and built a five-stamp mill the first in the district at a well near the lake bed in 1887. (Alas, gone of the sandstorms for which the desert is famoush later buried the plant.) Yet even with such a favorable start, mining remained stunted for nearly a decade.

Starting in 1895, strikes of moderate and high grade ore stirred the region's mining circles. The owner of the Gypsy Mine personally brought in 16 men, a train of three wagons and 12 horses, machinery, camp equipment, and enough supplies to last two months. By early 1896, the district had become goverrun with miners and prospectors. Two county supervisors came across 20 teams heavily loaded with prospectors' outfits. The Redlands Citrograph gushed that the next rush in mining circles will be to Virginia Dale. Mark the prediction. Soon mills will commence their ceaseless clatter and then money will begin to go out in streams. Keep your eye on Virginia Dale.

About then, a settlement of adobes grew up around a well dug by Lyons (Burt's Well), near the Virginia Dale mill. A post office, served by daily mail deliveries from Cadiz, was established in November, 1896; supplies and lumber were still teamed by Walters Station (the present Mecca), on the Southern Pacific Railroad, to the south. Weeks later, the county supervisors were asked to establish a full-fledged court; township. Now when they get a justice of the peace and a couple of constables, together with a deputy sheriff, Virginia Dale will blossom out into a regular, old fashioned, flourishing mining camp with all the necessary concomitants.

These words were hardly an exaggeration. About 600 to 700 men were doing ga great deal of workh in a 12x16-mile district in early 1897. Dale City was platted in March. gThings out in Virginia Dale are lively, very. Dale City supported two stores, the post office, a blacksmith shop, wagon and stage lines running to a railroad, and other concomitants of civilization will very shortly materialize, everything is lovely.

The district was a poor man's dream. Eight to 10 dry-washing machines were at work in June, 1897. That fall, 15 men were taking out $1,000 in placer gold a week. Despite the heat, 40 to 50 men worked in the district during the summer of 1898. An estimated $25,000 had been taken out of the placers in 15 months.

The lode miners, too, were doing well. By the fall of 1898, four small stamp mills were running, and the mines were turning out $1,000 a week by early 1899. Two of them were soon down several hundred feet.

But this boom began to fizzle. The placers were petering out, and the lode mines were slow to develop. Nor was the weather wholly inviting to the tenderfoot. With temperatures hitting 125 degrees F., most of the mines suspended work during the summer, although rich deposits at the Capitol (Capitola) group kept operations going year round.

The district's isolation remained a greater problem. Freight and mail were carried along roundabout routes through the present Joshua Tree National Monument to Walters Station (Mecca), Banning, and Palm Springs, about 60 to 80 miles south. The Dale-Walters circuit, of about 150 miles, required five days: the Dale Banning round trip took six days, It might take up to four weeks for a replacement part to arrive. Once, after the O.K. had drilled holes for blasting, it was learned that the mine lacked the explosives to fire the shots. It is but another illustration of 'so near and yet so far.'

It was little wonder that freight usually cost $20 a ton. To cross the 4,600 foot summit of Pushawalla Canyon, one teamster would lock the rear wheels of his wagon with chains and a brake log, then half drag the wagon, chains grating and wheels screeching against the boulders, 20 yards up the grade, rest a few minutes, and repeat this routine eight to 10 times.

The lack of water, however, remained the most serious hindrance to mining. From the district's scattered springs and wells, placer miners had to bring water 10 miles. The Ivanhoe mine and mill brought water four miles, the O.K. nearly 10 miles, and the Brooklyn a record 23 miles. These drawbacks took their toll. Only 63 persons lived in the district in mid-1900, when mine owner Charles B. Eaton asserted that anyone with gcapital and grit enough to invest in a powerful pumping plant could bring the camp out with a rush and make money for all interested, Eaton did not have long to wait. First, the mining that still went on lode mining had shifted south five, 10, even 15 miles into the Pinto Mountains. And fully developed lode mining required massive supplies of water.

The company that owned the Brooklyn and Los Angeles mines installed a pump near Dale in the spring of 1901 and laid an eight-mile pipeline over a divide to the Brooklyn and other properties. Though the plant was considered a success gas far as it goes, its daily output of 5,000 gallons of warm, heavily mineralized water could barely supply the needs of the Brooklyn and the O.K., each with its own thirsty mills and thirsty men.

Other changes followed. The Virginia Dale district was reorganized in January, 1902, as the Citrograph joked: The miners over in the Virginia Dale mining district 'gat themselves together' the other day and declared that 'Virginia must go.' And she incontinently vamoosed. Which all means that the name of the district has been shortened to 'Dale.' Meanwhile, the county built a wagon road from Amboy, 35 miles away, in contrast to the 75 miles to Walters. A few months later, the town and post office (May) moved eight miles southeast, to a flat below the up and coming lode mines. Since Dale had no. hotel, overnight visitors would sleep in the store. Mail still arrived from Palm Springs once a week, but a well circulated petition led to making Amboy the jumping off point by early 1903.

As Chase later observed, this shortcut proved to be a formidable route. Travelers paid $5 to ride in a buckboard stage from Amboy; the barren lunch stop was humorously named Lakeview Hotel. Passengers found they' could make better time up the grade from the Amboy salt flats by walking.

Outside new Dale was a tiny graveyard. For years, a wooden headstone marked the grave of Charles Thomas, a miner from the O.K. In June, 1903, Thomas, who was said to be drunk, went after a $400 gold brick about to be sent inside" to the coast. Brandishing his six-shooter, he marched the population of Dale to the post office, where constable Joe Wagner had left his gun. Wagner was told to get his gun and get it quick. Wagner stepped inside, picked up his pistol, and shot through the window. Thomas died instantly. Wagner received the hearty thanks of the Dale people for ridding the camp of a desperado and would-be thief.

Nearby stood the heart-shaped marble headstone of Carl P. McCabe. The son of saloonkeeper Percy McCabe and his wife, Adaline, Carl died in January, 1904. He was 10 weeks old. Even old-timers could become victims. Acting upon a bet, Matt Riley set out on foot for Mecca (formerly Walters) one summer day. He carried only a bottle of bourbon. Riley died within sight of an oasis. And Sam Joiner, who regularly carried long 2x8-inch timbers over his shoulder, was felled by heatstroke. His load pinned him until the sun set, when it became cool enough for him to recover.

Though Dale served about two dozen mines, two were especially important in building up the district.

Though only a small producer, the Ivanhoe built a two-mile road to Dale, brought in crushing and cyanide plants, and laid its own pipeline from Ferguson's Well, near the dry lake, to tanks at the mine. The company brought the district closer to the outside world when it joined the Brooklyn in building a telephone line to Amboy in late 1903. Up to 25 men worked at the mine then. Besides the Brooklyn and Ivanhoe, the line connected the Los Angeles, O.K., and Supply mines and the town.

The Brooklyn, however, was considered the ideal of legitimate mining. As early as mid-1902, its mine and mill were running night and day, and its pump was furnishing gsplendid water.h Tucked in a pocket of a hill in the Pintos, the camp in April, 1906, consisted of houses and quarters for the men, dining room and a kitchen, and stables. A recently modernized six-stamp mill overlooked the camp.

Coming into prominence was the Supply Mine. The Supply contained the largest ore bodies and most extensive workings in the district, a six-stamp mill, crushing and cyanide plants, and 25 employees in late 1903. But litigation between H.A. Landwehr, a long-time mine owner, and his fellow stockholders closed the Supply after 1908.

When young Fred Vaile, fresh out of Pomona College, arrived during the spring of 1909, the town was about dead. Only the Brooklyn Mine was active. The The only places still doing business were the Shamrock and Dale saloons, a store, and the post office; the barbershop and blacksmith shop were empty. High on a hill stood the redlight district" one shack. For $50, Vaile bought a fully furnished cabin one of only two in town that contained a bedroom, living room kitchenette, and the only screen door in camp. It was easy to see why Vaile could get in easily. The population of the town and mine camps dipped to 41 a year later, early 1910. Months later came this report: No election was held at Dale once a big mining camp. Like Calico the old camp has gone back to the desert.

Dale experienced one more important revival. Landwehr, who finally won back title to the Supply and its sister, the O.K., leased the two mines to the United Greenwater Copper Company in the fall of 1911. United Greenwater had fleeced investors at Death Valley a few years earlier and was now awash in cash. United Greenwater was working about 30 men in late 1912, then deepened the main shafts, to 1,100 feet, and finally installed a cyanide plant and a larger mill. The Supply became the most important producer in the district. The property produced so much gold that two workmen stole a bucket of precipitates and took off for Indio. But the precipitates leaked through a hole in the bucket, and a posse caught up with them at Cottonwood Springs, a well known oasis. But postmaster Isaac (Ike) Reed was more successful. Though a former justice of the peace, Reed fled with $1,075 in postal funds. A Blythe paper joked: Perhaps Reed got thirsty and went out to Salton Sea for a drink, as water is scarce at Dale, the supply for the camp having to be brought four miles up hill. Perhaps not surprisingly, the post office was moved to the Supply Mine's camp in early 1915, and Dale was abandoned.

The various booms had created three settlements: the original Dale City, near the dry lake; New Dale,h to the south; and gDale the Third,h at the Supply Mine. Another veteran desert traveler, J. Smeaton Chase, found this string of settlements of interest while making a horseback journey in July, 1915.

First, at Lyons' (Burt's) Well, only a few scraps of adobe wall remained to mark the site of Dale City, where he gcould barely find shelter from the wind in what was left of Virginia Dale. The historian of a mining camp must be early on the scene if he is to find anything more than the ground on which it stood.

New Dale had degenerated into a row of little buildings that served as blind pigs, or speakeasies, a sort of parasite whose only reason for being was to help the miners of Dale to get rid of their money. A water trough and wary man remained.

Riding up the stairway-like street at the Supply Mine's camp, Chase found a more welcome reception. That friendly chap, the cashier, gat once took charge of me as an unexpected guest; insisted on my taking his room for my own, and quartered Kaweah in the 'Company's' stables. Other conveniences were offered by the resident doctor, and in effect I was made free of the camp.

Chase found 50 to 60 men, half a dozen women, about 10 children, and one gbadly spoiled baby. The mining operation was ga highly organized affairh with electric lights in the buildings and water piped six miles from the lake. Day and night the whirr and crash of engines goes on unceasingly. It was strange to wake at night and hear the roar of machinery in that remote place.

Besides the mine structures, the village consisted of a score or so of temporary looking houses and cabins, spotted about without any pretense of order. A store, with kitchen and diningroom attached, and a cashier's office of stone are all the buildings of any size. The post office shares quarters with a Club-room containing an antique pool-room, the felt worn to a curiosity and the pockets as hopeless as a bachelor's. Relics of the Fourth remained in the shape of a wire cable stretched across the street with fag ends of rockets and Roman candles still attached.

This was the Supply Mine at its peak. It was then employing about 80 men. (In contrast, eight to 10 men worked at the Brooklyn.) But the company was running into water and hard-to-work ore deep in the shaft; Landwehr reportedly was becoming more difficult to deal with. The company cut back its operations; the post office closed in October, 1915; the stage line to Amboy was discontinued in 1916, about when all work at, the Supply and Brooklyn was halted. For several years, new Dale remained intact. A government geologist found a deserted town in 1918. Only eight residents lived in the area in 1920, though the veteran miner Sam Joiner still inhabited the few buildings. When Dave and Anna Poste arrived to rework the Virginia Dale in 1923, the Dale Saloon remained in immaculate condition even to the cues and chalk lying at the pool table. In what must have been the Dale Saloon, a writer for Touring Topics in 1928 saw a pool table, water cooler, and safe. Bottles still stood on the pool table. Envelopes and old papers gathered dust in the post office.

But as roads continued to penetrate the region, Dale was ignominiously torn apart. Campersshot apart the thousands of bottles behind the saloon, which was burned. Mickey Thornton, who moved to the district in 1930, took apart the post office and used the lumber to build a shack and burned two sacks of mail, though he later hoped to see a revival of the camp. The Postes saw a car from Los Angeles carry away a dresser, complete with drawers and a sun-warped mirror; another auto had a pack saddle on its hood.

A final revival, (during the 1920's and 1930's, considerably added to the district's output. But because gold mining was considered nonessential to the war effort, a presidential order shut down gold mines throughout the United States in 1942. The Brooklyn had produced more than $150,000 in gold, the Carlyle more than $125,000, the Gold Crown $385,000, the O.K. $200,000, and the Supply more than $500,000.

Dust unto dust; ashes unto ashes. Not even vandals could erase the romance of the Dale district. Riding south on his horse in 1915, Chase could only marvel at the decrepitude of that narrow canyon gwhere every hillside had a metallic look. Everywhere were prospect holes, or deeper workings where the mountain had spewed out piles of glittering gray rock. Here and there were scraps of machinery, old windlasses and boilers, dragged here at enormous expense, now mere rusty monuments to the ruling passion; though to be fair, one must say to man's energy, hardihood, and determination, as well.

SOURCES: The mining and milling operations were fully reported in the Mining & Scientific Press, 1894-1905, and the Los Angeles Mining Review, 1899-1904, and the Redlands Citrograph, 1895-1907. Two modern mining operations (the Brooklyn and Supply) impressed George Wharton James, The Wonders of the Colorado Desert (Boston, 1906), and J. Smeaton Chase, California Desert Trails (Boston, 1919). Philip Johnston visited the ghostly ruins: Derelicts of the Colorado Desert, Touring Topics (Westways), February, 1928, pp, 14-18, 37, 39, and 44-42.

The best modern account is in Lulu Rasmussen O'Neal's classic history of the Twentynine Palms area: A Peculiar Piece of Desert (Los Angeles, 1957), which has recently been reprinted. Interviews form the basis of three popular accounts: Harold and Lucille Weight, eds., Ghost Town With Restless Feet,h Calico Print (Twentynine Palms), June, 1951; Ronald Dean Miller, Mines of the High Desert (Glendale, 1965); and Johns Harrington, Flight from New Dale,h Westways; March, 1943 (v. 35), pp. 14-15. These accounts all contain interesting photos of Dale II. William Clark's Gold Districts of California (cited earlier) contains somewhat general figures on the output of the leading mines. The district seemed to be a favorite of L. Burr Belden in the San Bernardino Sun-Telegram: Dale District Long Producer of Rich Gold Ore, Feb. 21, 1954, p, 20; $100 Ore From Dale Noted by Mint's Director, June 23, 1957, p 24; and Valley Leaders Are Owners of Brooklyn Group, June 30, 1957, p. 20.