Ivanpah

Copper World

What a disappointment. A newspaper publisher in

San Bernardino

had just received the annual report of the United States

Mint, yet it was full of errors and incomplete. Not a word had been

written about “our most productive mines,” near Ivanpah.

Lured by the rush to the White Pine Mining District, in northeastern

Nevada, a prospecting expedition found promising copper and silver

veins in the Clark Mountains, in the eastern Mojave Desert, in early

1869. This was about 200 miles from

San Bernardino. The party named the

district after Albert H. Clark, a businessman in Visalia, who was one of

the supporters of the expedition. The group also organized the Yellow

Pine Mining District, adjacent to the Clark district, in Nevada. The

Piute Company of California and Nevada was organized in June of 1870 to

develop the veins.

The company had an impressive pedigree. One of the trustees was John

Moss, the leader of the expedition; a noted mountain man, he maintained

friendly relations with Indians along the

Colorado River. The

secretary

was Titus F. Cronise, who had recently written an encyclopedia on the

state’s resources. The superintendent was J. W. Crossman, who was

becoming an important writer on mining.

The Piute Company planned four towns. Two of them, Cave City and

Pachocha (variously spelled), were never built. The third site was Good

Spring, in the Yellow Pine district. Ivanpah, a 160-acre townsite, was

laid out at a spring on the southeast slope of Clark Mountain, eight or

nine miles southeast of the mines.

Despite the isolation and heat, 300 men were in the district by the

summer of 1870. The first ore was shipped out in September, to San

Francisco. Freighting cost about $70 a ton, but the ore was yielding as

much as $2,000 a ton, mainly in silver. By August of 1871, Ivanpah

contained 15 buildings, including a hotel, two stores, the office and

headquarters of the Piute Company, and small houses, all of them built

of adobe, covered with good shake roofs. Three of the buildings measured

40x60 feet, including the hotel, the largest structure in town. (These

might have been tents.)

The mines were on Mineral Hill (also called Alaska Hill), eight or

nine miles northwest of the town. The most promising properties were the

Hite & Chatfield claim (later renamed the Lizzie Bullock) and the

Monitor and Beatrice, owned by the McFarlane brothers—Tom, Andrew, John,

and William. The work force included Indians, Mexicans, and Anglos;

among them were several pioneers of the Kern River mines:

Dennis

Searles,

William A. Marsh, and the McFarlane brothers. (Six miles

southwest of Ivanpah was the

Copper World

claim, which would remain

unworked for three decades.)

The original operations were primitive. The Beatrice Mine No. 2,

owned by the McFarlanes, was equipped with only a hand windlass, in

1871. John McFarlane’s house, office, and sleeping quarters, which

contained several berths, consisted of a very large tent, where he had

several mineral cabinets, which held more than 200 specimens. Since the

mines were dry, Indians were employed to haul it by pack train from

Ivanpah Spring. Mexicans were employed to work the ore in

arrastres,

or

circular stone mills. They received $125 a ton, which meant that lower

grades of ore, worth at least $150 a ton, had to be left on the dump.

Even so, the firm of Hite & Chatfield earned a $20,000 profit in

1872. Teamsters arrived from

San Bernardino

with supplies and returned

with heavy loads of ore. During six months in 1873, the mercantile firm

of Brunn & Roe forwarded $57,000 worth of ore to San Francisco.

With returns like those, the mine owners could afford to develop

their properties. In November, 1873, the McFarlane brothers put up a

small smelting furnace and a comfortable house. About early 1875, they

moved a five-stamp mill from the

New York Mountains

to a hill above

Ivanpah, where water was available. By then, their main mine, the

Beatrice, was nearly 300 feet deep. The brothers also incorporated the

Ivanpah Consolidated Mill and Mining Company, which was often called the

“Ivanpah Con.” By mid-1875, the district had produced $300,000. J. A.

Bidwell and a partner, who had bought the Lizzie Bullock Mine, built a

10-stamp mill near the Ivanpah Consolidated in 1876. It started up in

June.

Regional and national depressions, which had begun in 1875, finally

affected the Clark district in 1876. Both the Bidwell and Ivanpah

Consolidated mills had difficulty getting enough ore to run full time.

About $40,000 in attachments were filed against the Ivanpah

Consolidated. Apparently, the property was sold and operated only

intermittently through 1877, although the McFarlanes were kept on as

managers. One writer charged that the mines never had been properly

developed, having been “gouged too much by incompetent miners.”

It’s likely that Bidwell’s operation became the main producer then.

In late 1877, he overhauled his mill and increased his force at the

Lizzie Bullock Mine, to 20 in August, 1878. Both mills ran steadily, but

well into 1879, Bidwell continued to send out heavy loads of bullion,

including one shipment worth $8,000.

The camp reached its peak about then. A post office was established

in June of 1878. By April of 1879, when more than 100 hands were working

on Alaska Hill, the business district comprised two saloons, stores,

blacksmith shops, shoemakers’ shops, hotels, and hay yards, besides one

butcher shop and “neat and comfortable” houses. By early 1880, about 65

people were living in town and about the same number at the mines. In

May, two printers, James B. Cook Wilmonte (Will) Frazee, started a

weekly newspaper, the Green-Eyed Monster, but they had to suspend it

after a few issues.

Though the Ivanpah Consolidated had produced a reported $500,000 in

bullion by the end of 1879, it continued to sink into debt. The owners, a

San Francisco company, resorted to issuing scrip, for which it

neglected to pay a 10% tax to the federal government. After failing to

pay its employees for several months, the company suspended work. The

government won a judgment for $1,480 and sent out E. F. Bean, a deputy

collector for the Bureau of Internal Revenue, to attach the property.

Upon his arrival, in mid-May of 1881, a dispute arose; two days later,

John McFarlane tried to shoot Bean, who managed to get off a shot first.

McFarlane died instantly. A judge in

San Bernardino

ruled that the

killing was “a clear case of justifiable homicide.”

The district shipped out at least $162,000 in treasure in 1881, but a

decline soon followed. Most of the population departed during the early

1880s. Only 11 residents remained in early 1890. About the only

businesses left in December of 1892 were a store and boardinghouse and

the post office, which Bidwell and his wife ran. Soon after collecting

mineral specimens for San Bernardino County’s exhibit at the World

Columbian Exposition, in Chicago, Bidwell died. His widow received $75

from the county. A depression followed, in June of 1893, and the price

of silver fell to 58¢ an ounce, its lowest level, in 1898. The store

closed about then. The post office was moved in April of 1899.

For nearly three decades, the Copper World discovery

remained neglected. In August of 1878, James Boyd, who owned the

property, built an experimental smelting furnace in San Bernardino, but

nothing materialized.

But that changed in 1898, when new owners began developing the

property; it would become the largest copper producer in Southern

California. A large smelter was built at Valley Wells (also called

Rosalie Wells), several miles below the mine, in early 1899; the Ivanpah

post office was moved to Valley Wells in April, and its name was

changed to

Rosalie. Eighty-five

men worked at the mine and smelter.

Every four days, long mule teams would haul 20 tons of copper

concentrate, or matte, to

Manvel,

30 miles away, and would return with

coal and supplies. The operation produced 11,000 tons of matte until

litigation forced the mine, smelter, and post office to close in July,

1900, but the Copper World was soon revived.

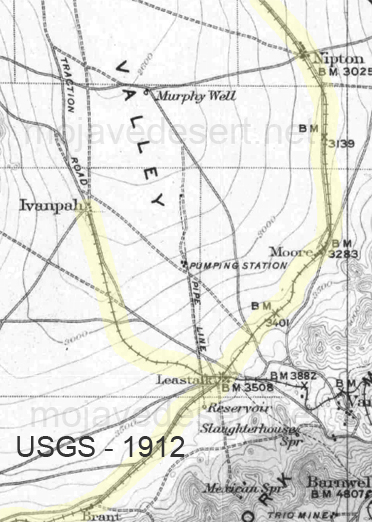

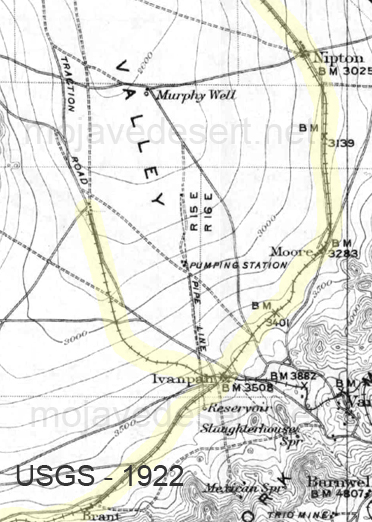

This time, the

California Eastern Railway

built a 16-mile extension

from

Manvel

into the Ivanpah Valley, in early 1902, and established a

shipping point. Known as Ivanpah, the station contained an agency and

telegraph office (housed in a box car), several stores, and other

buildings. From 25 to 30 persons lived there. A post office, also called

Ivanpah, was established there in August, 1903. But costly, wasteful

operations forced the Copper World to shut down after a year or two.

When the

San Pedro, Los Angeles, and Salt Lake Railroad

was completed,

in early 1905, the line passed within a few miles of Ivanpah station.

The post office was moved to nearby

Leastalk, a station at the junction

of the

Salt Lake line and California Eastern. The

Copper World

reopened

in 1906; it produced 487,000 pounds of matte in 1907 alone. But the

matte was shipped through Cima, another station on the Salt Lake line.

The operation was large enough to warrant the formation of a local of

the Western Federation of Miners. When the Copper World shut down again,

the California Eastern abandoned its station at Ivanpah. Four or five

buildings, all of them vacant, were burned in April, 1908, supposedly by

tramps—the usual suspects.

World War I drove up the price of copper (and other metals). The

Copper World was reopened in 1916, a large blast furnace was later

built, and the work force rose from six to 60. A tractor hauled the

matte to

Cima. But when the war ended, in November, 1918, metal prices

declined, and the Copper World was shut down for the last time. The

California Eastern tore up its tracks in 1921. Several years later,

Leastalk

was renamed South Ivanpah, which was soon shortened to Ivanpah.

The post office remained open until 1966.

Ivanpah District

Location and History

The Ivanpah mining district is in northeastern San Bernardino County about 35 miles northeast of Baker and south of the Mountain Pass-Qark Mountain area. The district includes the mines in both the Ivanpah Range and the Mescal Range, which is just to the west. Gold mining began here at least as early as 1882, when the Mollusk mine was opened. Moderate mining activity continued in the district until about 1915, and there was some work again in the 1930s.Geology and Ore Deposits

The western part of the district is underlain predominantly by limestone and dolomite, with smaller amounts of shale, sandstone and dacite. To the east is granite and gneiss, and to the south is quartz monzonite. The gold deposits are in quartz veins or mineralized breccia, which occur chiefly in granitic rocks or gneiss, although the Mollusk vein is in dolomite. Other mineral commodities in the district are silver, copper, tungsten, tin, barite, fluorspar, and rare earths. As in the Clark mining district to the north, the metal-bearing deposits are associated with several major thrust fault zones. Mines. Kewanee, Mollusk $250,000, Morning Star, New Era, Teutonia.Bulletin 193 California Division of Mines and Geology 1976

The California Eastern Railway built a 16-mile extension from Manvel into the Ivanpah Valley, in early 1902, and established a shipping point. Known as Ivanpah

In November, 1918, metal prices declined, and the Copper World was shut down for the last time. The California Eastern tore up its tracks in 1921. Several years later, Leastalk was renamed South Ivanpah, which was soon shortened to Ivanpah.

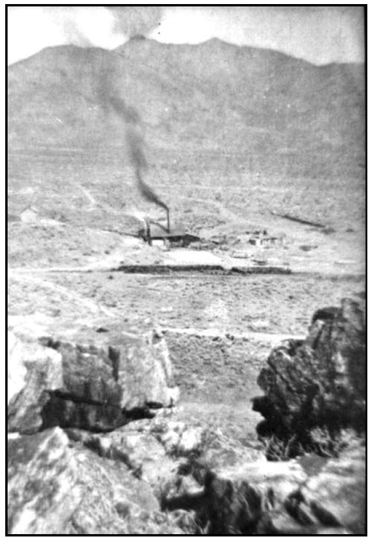

Bidwell mill at Ivanpah