Borate and Marion

GOLD AND SILVER were not the only minerals sought by the mining world.

A borate of lime known as “colemanite,” with “prismatic crystals that sparkle in the sun like diamonds,” was found in 1882 in Mule Canyon, a twisting defile with “more crooks and pitches than the streak of chain lightning.” The veins were only 12 miles from the newly established station of Daggett. In what was probably the first development of a nonmetallic mineral in the Mojave, William T. Coleman, a San Francisco business magnate and the namesake of the mineral, bought the claims and began working the deposits.

After Coleman's company failed, Francis Marion (Borax) Smith bought the property in 1890. Development began in earnest. Out of three deep shafts came 12 tons of colemanite a day-- "sufficient to meet the requirements of the market” --which was hauled by a 14-mule"team to Daggett and then sent north to Alameda for refining. “

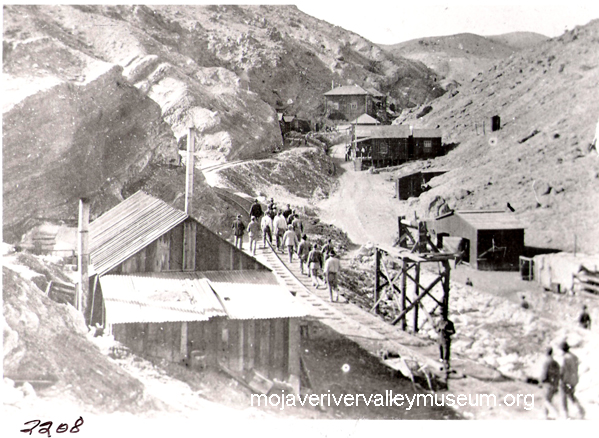

Mining in this barren, isolated site was difficult. All water had to come from Daggett, a day- and-a-half journey for wagons. Smith replaced the coal-eating steam engines at the mines with gasoline engines, but an attempt in 1894 to replace mule teams with a monstrous steam tractor named Old Dinah failed. Though few miners received any letters, each paid one dollar a month for the pleasure of having a girl bring mail five miles from Calico two or three times a week. The experience with Old Dinah illustrated the growing importance of borate minerals. The borates generated more revenue in 1895 than all the county's silver mines. About 75 men worked in the mine in early 1896, though employment would fluctuate with the demand for borax. Small gasoline engines hoisted the borates to bins, from which three 20-mule teams would haul the mineral to Daggett. The activity was so great that a post office named Borate was established in July, 1896.

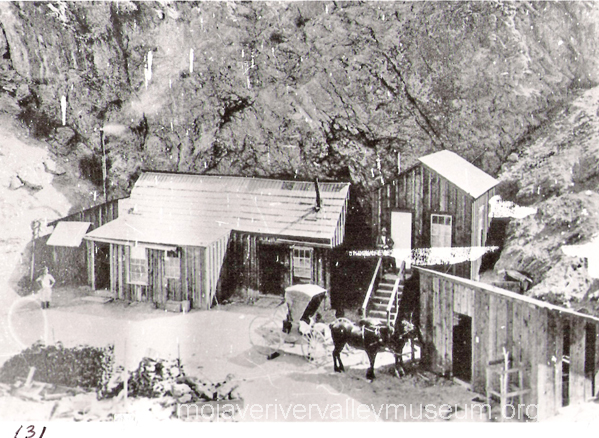

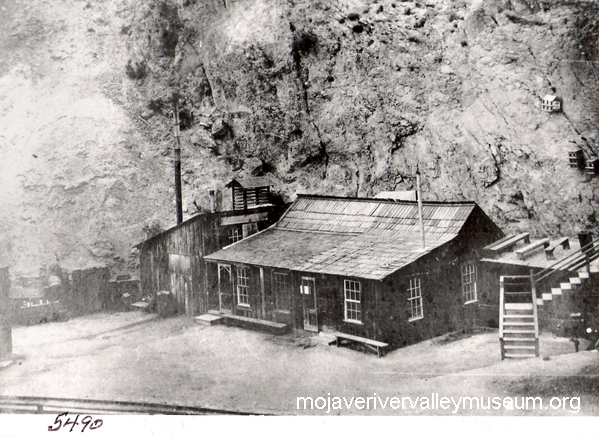

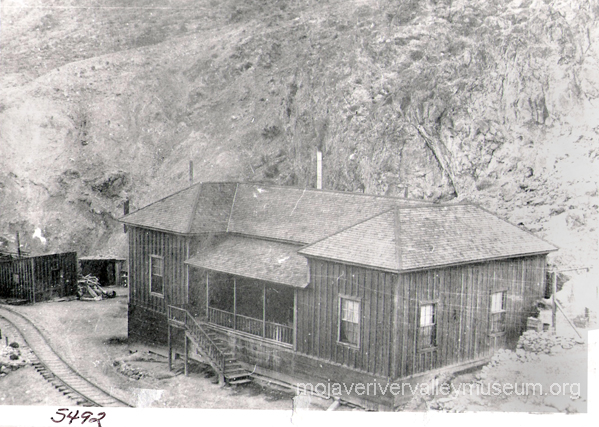

The camp by then comprised a simple cluster of cabins jammed between the road and the walls of Mule Canyon. Although many miners preferred to live in dugouts during hot weather, the company provided a bunkhouse, a store, which later housed the post office, an understocked reading room, and houses for the superintendent and storekeeper, who had families. On a steep hill overlooking the mine stood “The Smith House,” which was used by Smith and other company officials. The house had to be attached to the rocks with guy wires to keep the area's high winds from blowing it over.

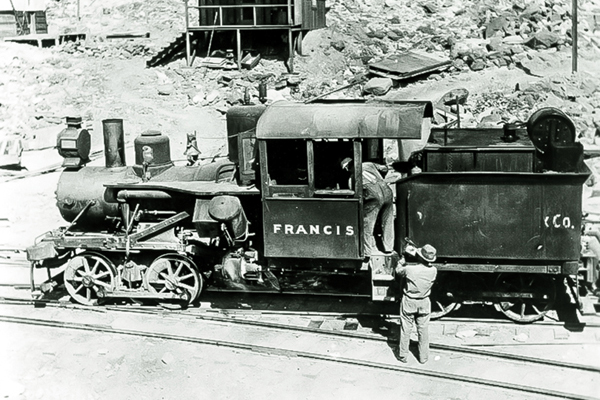

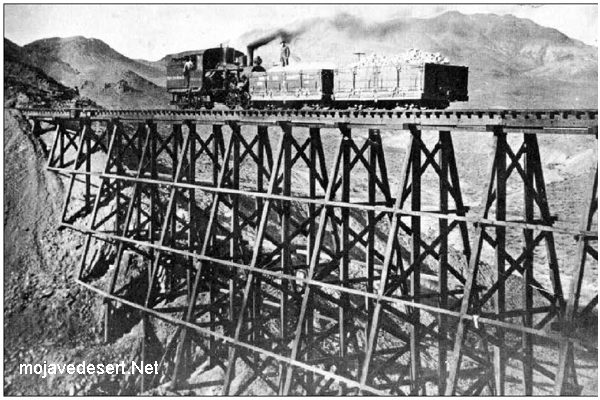

It was a wonder that Smith's concern, Pacific Coast Borax Company, was able to maintain even this simple operation. The demand for borax had fallen during the depression of the 1890's; vicious competition kept prices low. Management had already cut the meager wages of its miners from $3 a day to $2.50, though the price of board was cut from $1 a day to 75 cents. Smith had to find another outlet for his product. That summer, 1896, Smith sailed for Europe, where he was introduced to two young men who were making food preservatives. They needed a steady supply of borax. Without delay, Smith engineered a merger of their two companies and, the next year', they built a modern refinery at Bayonne, New Jersey, to fend off competition in the East. Then, in early 1898, the new regime built an 11-mile narrow-gauge railroad, the Borate 8. Daggett. Over it rolled two locomotives, the Francis and Marion, and flatcars that could be converted into mineral carriers. Four miles north of Daggett, at Marion siding, a calcining plant was built to roast low- grade ores. High-grade ore and the roasted product were shipped to Alameda (later to Bayonne) for refining. In mid-1900, exactly 100 residents lived at Borate and 17 at Marion, including several women and children.

But trouble continued to haunt Smith. Though large, the mineral deposits at Borate were becoming less pure and harder to refine. The high cost of mining and processing made borax mining a marginally profitable business at best. Meanwhile; small but well-established rivals, notably the Sterling Borax Company, were pressing the Pacific Coast Company hard. Smith devised a strategy to rescue his holdings. In late 1902, he sent prospectors to Coleman's original claims in the Funeral Range, just east of Death Valley, and even considered the construction of a steam-tractor road. Spurred by the gold and silver strikes in western Nevada, Smith began work in 1904 on a railroad to Death Valley, the Tonopah & Tidewater. The summer was so hot that he closed the Marion plant and reduced the force at Borate to 25 men.

The relocation of borax mining was no small matter. Only a year before the shutdown, 250 men worked in the mine's two 600-foot shafts. The Bayonne plant by then was processing all the ore.

/

/But Borate would soon be history. Even before the arrival of the Tonopah & Tidewater Railroad, a crew was taking out ore from the newly developed Lila C. Mine, one of Coleman's original claims in the Funeral Range. Rails finally reached the Lila C. in August, 1907. To kill off his rivals--or so he thought--Smith cut the price of his refined product from seven cents to five and a half cents.

Trestle to Marion

Smith shut down the Borate operations that October, though the post office lingered until December. The buildings, machinery, and employees were moved to the Lila C. The rails of the Borate 8. Daggett were torn up and the locomotives and the rolling stock sold.

SOURCES: One of the early rushes was covered by the Calico Print in 1885. The early operations under Smith were observed by John Spears in his Illustrated Sketches of Death Valley and Other Borax Deserts of the Pacific Coast (Chicago, 1892) and by the State Mining Bureau in Report 11 (1892).

Because the borax industry was intensely competitive, only a few items leaked out to the press, such as the Mining &. Scientific Press, Needles Eye, Saturday Review (San Bernardino), and Redlands Citrograph. One of the few full-length descriptions of the operations was written by Day Allen Willey, “Borax Mining in California,” Engineering & Mining Journal, Oct. 6, 1906 (v. 82), pp, 633-634.

Full photographic accounts appear in Ruth C. Woodman, comp., The Story of the Pacific Coast Borax Company (Los Angeles, 1951), an authorized history' David Myrick's Railroads of Nevada and Eastern California, II (cited earlier); Patricia Jernigan Keeling, ed., Once Upon a Desert (already cited); and George H. Hildebrand, Borax Pioneer: F.M. Smith (San Diego, 1982), a thorough, well- balanced biography.

GHOST TOWNS

of the Upper Mojave Desert

Volume I: San Bernardino County

by Alan Hensher and Larry M. Vredenburgh

(c) 1986

Calico

Minneola

Daggett Garage

Daggett Garage Backstory

Old Dinah

Borax

.jpg)

Marion ore processing plant

Old Dinah

Bill Boreham - Alf's Blacksmith Shop

Colemanite (USGS photo)