20-Mule Teams

The saga of the twenty mule teams began with the discovery of borax in California in 1881, This mineral, used for thousands of years in ceramics and in the working of gold, previously had come from Tibet and Haly. Its discovery in California's Death Valley resulted in a rapid increase in the use of borax in the United States in various industrial processes and as a house- hold cleanser.

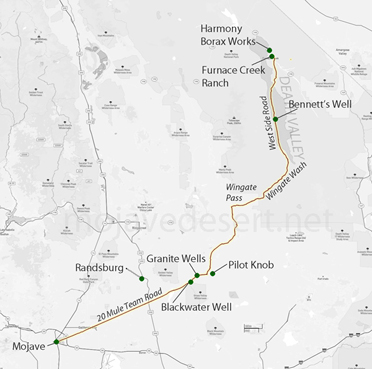

With a growing demand for borax and an apparently unlimited reserve of crude ore, a practical and economical method had to be devised for freighting borax ore from the “mines” in Death Valley's vast dry lake beds to the nearest railhead at Mojave. It was the hottest, driest, roughest most desolate 165 miles imaginable.

William T. Coleman, owner of the Old Harmony Borax Works near what is now Furnace Creek Ranch, took on this Herculean task. The borax transportation system had to be built around the capabilities and limitations of mules, horses, men and wagons.

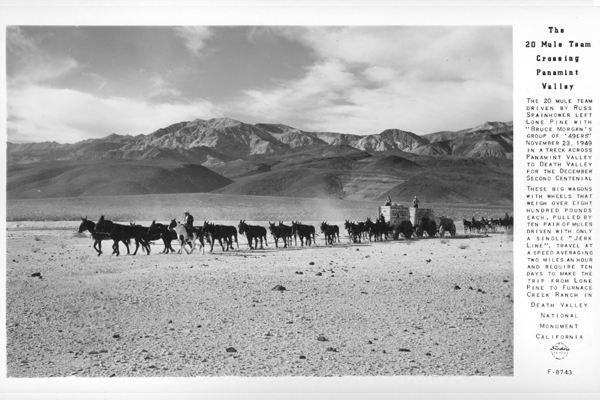

He had seen 8 and 12 mules hauling heavy loads. and had observed that the payload increased disproportionately with each added pair of animals. Experimenting, Coleman tound that twenty mules couid move 36 tons with relative ease. The mules were hitched to single-trees and double-trees hooked into an 80-foot chain which ran the length of the team and fastened directly onto the lead wagon. Ed Stiles. the most expert “long-line skinner” of the time, was hired to drive the first twenty mule team between Harmony and Mojave.

The route finally decided on, trom Death Valley to Mojave. covered 165 miles of raw, blistering temperatures (often running to 130° F in summer), desolate mountains and desert, and was dictated by the topography of the country and availability of water. Work crews were sent out to hack, blast and hammer a roadbed of sorts over this rugged wasteland. The mutes and wheels of the wagons were counted on to do the rest.

There arose the problem of survival, and that meant water and food. It was about 26 miles from Harmony to the first water at Bennett's Wells, five miles to Mesquite Wells, 53 miles to Lone Willow, 26 to Granite Wells, an easy six miles to Blackwater, then a 50-mile waterless stretch to Mojave.

Watering the mules

But a loaded team could travel an average of only 17 miles a day, so the gaps between natural water supplies had to be filled by caches of water transported in 500-gallon iron tanks on wheels (wooden tanks would have dried up and fallen apart when empty). Water, hay, and grain were spotted a day's journey apart. The natural springs also had to be improved by digging out and cleaning; in some places where springs were at a distance from the road, water was piped down. The men’s food (mostly bacon and beans) was carried along the wagons.

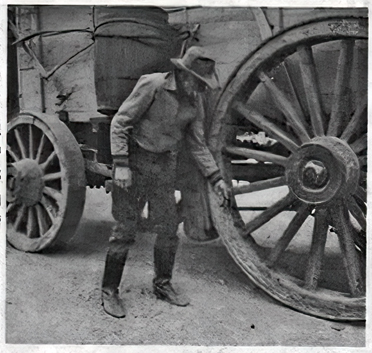

Perhaps the most difficult problem was designing and building wagons capable of hauling heavy loads of borax over the rough desert and mountain trails, a breakdown in the wrong the place could be a major disaster for both men and animals

The wagons were built in Mojave for $900 each, with rear wheels seven feet high and front wheels five feet high, each with steel tires eight inches wide and one inch thick. The hubs were eighteen inches in diameter and twenty-two inches in length. The spokes of Split oak. measured 5% inches wide at the nub.

The axle-trees were made of solid steel bars, 3'2 inches square. The wagon beds were sixteen feet long, four feet wide and six feet deep.

Empty, each wagon weighed 7800 pounds. Two loaded wagons plus the water tank (which held 1.200 gallons) made a total load of 73,200 pounds or 36 tons.

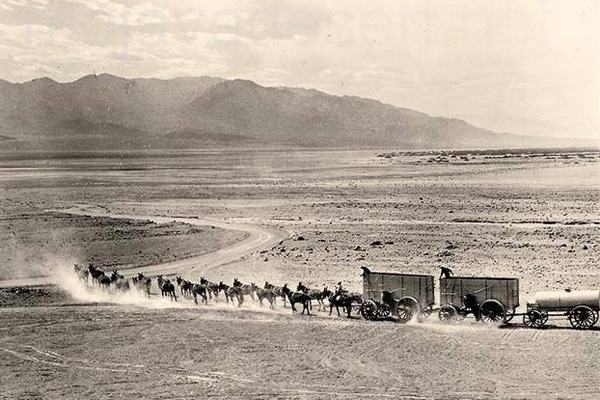

From 1883 to 1889, the twenty mule teams hauled borax out of Death Valley, over the steep Panamint Mountains and across the desert to Mojave. traveling 15 to 18 miles a day, a twenty- day round trip. During these years, the twenty mule teams carried over 20 million pounds of borax out of the valley without a single breakdown —a considerable tribute to the ingenuity of the designers and builders and the stamina of the teamsters, swampers, and animals.

Frasher photo - 1949

Today, a century later, one set of wagons is still in running condition and can be seen at the visitor's viewing point on the edge of the U.S. Borax open pit mine at Boron, California.

Other sets in Death Valley are displayed at Furnace Creek Ranch at the Old Harmony Borax Works

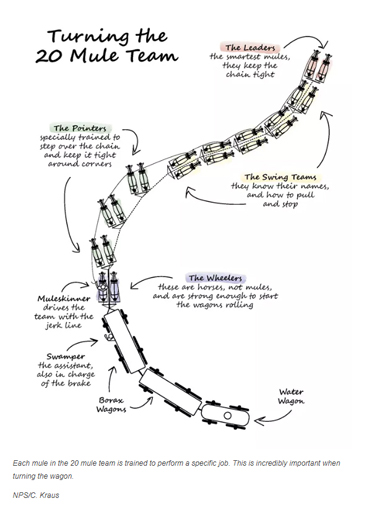

Each twenty-mule team crew consisted of two men. a driver (the muleskinner) and a swamper.

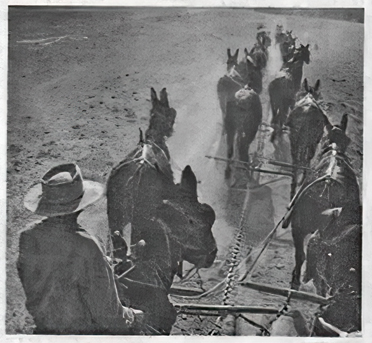

The muleskinner drove his team from the “box” of the first wagon, or. in rough going, from the back of the “nigh wheeler” or left-hand animal nearest the wheel. His only means of con- trolling the teams was his voice, and the “jerk line” was a long rope running through a collar ring of each left-hand mule up to the leaders. A steady pull turned the team to the loft, a series of jerks sent it to the right. A sight which never failed to win admiration was that of the “big team" taking a sharp turn.

The driver (mule skinner), besides driving, which of itself demanded great skill and strength had to be a practicing veterinarian. for he was responsible for curing any mule that got sick on the road, and a wheelwright to make minor repairs to the. wagons. The swamper helped apply the brakes on downgrades, helped stimulate the mules on upgrades, gather fuel, cooked. washed the dishes, unharnessed the mules at the end of each day's run and did other chores. Drivers earned $100 to $120 a month, swampers about $75. They were usually silent, short- tempered men: the loneliness, monotony, and hardships of their work made them no easier to get along with. There are tales of quarrels between swamper and driver, some ending in murder and lynching.

It was a hazardous life. Added to the heat, desolation, rattlesnakes, and a general chance of injury, the great wagons themselves were a menace. Brakes gave way at times on steep grades. Then the 36-ton juggernauts would thunder down the incline, hard on the heels of the frantic mules, the 'skinner yelling and hoorawing at his team in a desparate effort to keep them outrunning the wagons. Camp was made on the desert each night. The one-way trip, from mine to railroad point took about ten days.

Adapted from Twenty-Mule Team Borax promotional brochure

Freight

Mule Skinner

20-Mule Team Road

Eagle Borax Works

Harmony Borax Works

Mojave

Daggett

Borax at Death Valley

Borax