Mormon Fort

Mormon Fort - 2017

Mormon Fort at Las Vegas Springs sits on an older truth than the city that grew around it: water makes history in the desert. Long before Las Vegas meant rail depots, boulevards, and bright signs, it meant springs and meadow grass. A spring-fed creek once crossed the valley floor and spread into low, green patches that stood out sharply against the surrounding dry country. That reliable water drew Southern Paiute people and, later, traders and travelers moving between distant regions. Spanish speakers called the place “Las Vegas,” the meadows, because the grassland was the valley’s defining feature.

Those meadows also made the valley a practical waypoint. Desert travel is governed by stop spacing and animal needs as much as by distance. Routes do not simply run where a line looks straight on a map; they run where water and forage can be counted on. In that sense, Las Vegas Springs belonged to the same old corridor logic as the great trail networks that crossed the Southwest: movement from water to water, with each dependable spring acting like a rung on a ladder.

In June 1855, Mormon missionaries arrived from Utah and chose the springs as the site of a mission outpost. They built a substantial adobe enclosure often described as a 150-foot-square fort, with fortified corners and interior buildings. The word “fort” can mislead modern readers into picturing a purely military post, but its purpose was more traditional and practical than that. This was an attempt to convert a desert oasis into a stable, working place: a station where people could live, plant, repair, and host travelers. The spring-fed creek made irrigation possible, and the settlers diverted water into ditches to support fields and orchards. In a region where dependable water was rare, the capacity to grow crops and feed animals was the real power.

For a short time, the mission served as a way station for people moving through the valley. Travelers could pause, water stock, take on provisions, and regain strength before continuing across long dry stretches. In the older pattern of western travel, such stations were not luxuries. They were safety devices. The desert punishes optimism and rewards routine, and a reliable stop could turn a risky crossing into a manageable one.

The mission did not last. Crop troubles, leadership dissension, and discouragement combined to weaken the effort, and the outpost was abandoned in March 1857. The abandonment does not make the fort a failure in the larger historical sense. It reveals how unforgiving the desert can be to institutions that lack cohesion and dependable productivity. Even a well-sited oasis cannot carry a community if the daily ledger does not balance.

The springs, however, remained. The site re-entered the older pattern of desert economy: ranching and travel support. In 1865, Octavius D. Gass acquired the property and developed it into a substantial ranch that served travelers and nearby mining activity. After financial trouble, the ranch passed to Archibald and Helen Stewart, and Helen continued to operate it after Archibald’s death. Through these transitions, the real asset was always the same: water and the control of water.

That fact set the stage for the next hinge in the valley’s story: the railroad. In 1902, Helen Stewart sold the ranch and water rights to the San Pedro, Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad. When the rails reached the valley in 1905, a new town was laid out and promoted. From there, Las Vegas expanded into a major metropolitan center. The modern city’s growth can look sudden, but its foundation was old and plain. The railroad did not create water; it captured an existing water node and built a new kind of settlement around it.

Today, the Old Las Vegas Mormon Fort remains as a preserved fragment of adobe at the springs site, a reminder that Las Vegas began as an oasis before it became a city. It is a small structure with a large meaning. It marks the moment when a desert water place shifted from being a seasonal homeland and a travelers’ refuge into an organized station, then a ranch, then a railroad hinge, and finally an urban center. In the end, the story of the Mormon Fort is the story the desert tells again and again: where water holds steady, human plans return, even when the first plan fails.

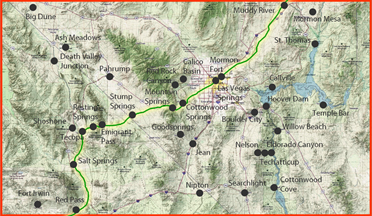

1908 map of Las Vegas, Nevada