Sherman Stevens' Timber Empire

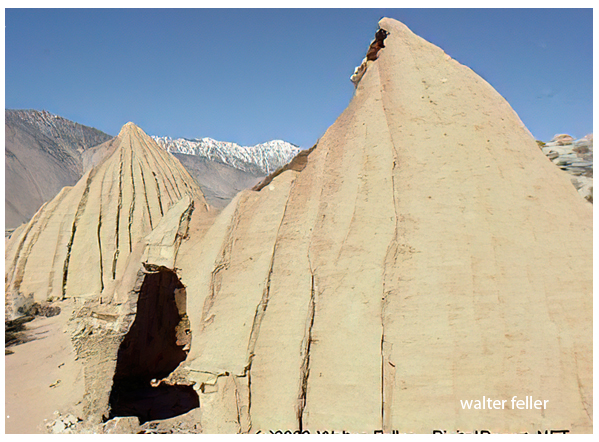

For decades, before erection of the historical marker, travelers along the west side of Owens Lake passed by two adobe charcoal kilns without knowing of their existence. Though some distance from the road, they were in plain sight if you knew where to look. But they blended so well into the landscape that they were discovered and visited only by a few who were willing to risk their auto on the old dirt road.

Cottonwood Kilns

Today these fascinating relics-fenced against vandals but sadly eroding from the elements-are about all that remain of a picturesque empire built by an Inyo County pioneer, Col. Sherman Stevens. His enterprise once spread from the Cottonwood Lakes near the crest of the Sierra to the silver towns of the Inyo and Coso Ranges up to forty miles away. His business was to supply mine timbers and smelter fuel for the flourishing camps of Cerro Gordo, Swansea, and Darwin. And in transporting his products he used a unique and wonderful combination of ox teams, wooden flume, mule teams, and a steam tugboat.

Born in New York about 1812, Stevens left home at sixteen and threw in his lot with the Western frontier. For a time he was active in the fur trade around the Great Lakes, and later built an early railroad in Michigan. Tall and robust, he joined the Gold Rush to California in 1851; in the next few years he made some fifteen business trips back and forth to the coast. He settled in Owens Valley in 1865, a year before Inyo County was formed, and in the midst of the Indian war. As early as 1867 he owned a mine at the new silver-lead camp of Cerro Gordo, high in the Inyo Range east of Owens Lake.

But like so many other Western enterprisers, Stevens' main contribution was not in digging for metal, but in providing supplies.

By the early 1870s, Cerro Gordo was booming through the hard-driving efforts of its principal mine and smelter owners, Mortimer W. Belshaw and Victor Beaudry. The bars of silver-lead bullion, hauled southward by Remi Nadeau's mule teams, were helping to bring new life to the adobe pueblo of Los Angeles. As early as 1872 nearly all the pinon pines and junipers on both sides of Buena Vista Peak had been cut and devoured for mine timbers and furnace fuel. An army of woodcutters, charcoal burners, and muleteers had used up the local supply.

At this point Sherman Stevens cast his eyes across Owens Valley to a new and almost inexhaustible supply of timber in the High Sierra. For over a year woodcutters had been chopping trees in Cottonwood and Ash Creeks, rafting the logs and charcoal across Owens Lake by flatboat and scow. But the cost was so great that $40 worth of charcoal was required to smelt a single ton of bullion worth $400. Stevens had to find a cheaper means of transportation.

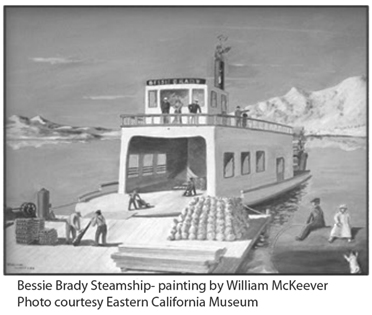

At this very time part of the problem was solved by the enterprise of James Brady, superintendent of the Owens Lake Silver-Lead Company. In partnership with Daniel H. Ferguson, he built a steamboat near his company's headquarters at Swansea, on the east side of Owens Lake. Eighty-five feet long, sixteen wide, she was shaped like a ferry boat and powered by a twenty horsepower engine and a four-foot propeller. On Independence Day, 1872, she churned over to Ferguson's Landing, five miles south of Lone Pine; here, while the population of southern Owens Valley looked on, Brady's little daughter broke a bottle of wine on the bow and spoke her own name, "Bessie Brady."

Second commercial lake steamer west of the Mississippi and the first west of Salt Lake, the Bessie Brady began hauling Cerro Gordo and Swansea bullion bars across Owens Lake at the rate of seven miles an hour. Even at this speed, she saved the four days' time that mule teams had formerly required in their trip around Owens Lake and back.

Stevens could use this advantage in transporting Sierra timber, but more than a dozen steep miles still remained between the west shore of the lake and the best timber stands high in Cottonwood Canyon. This problem the ingenious Stevens solved by planning a flume to carry the logs at least as far as the bullion trail from Los Angeles. From there, the mule teams could haul them down to the wharf on the lake near the mouth of Cottonwood Creek.

Together with his two sons, Sherman V. and Augustus C., the grey bearded colonel launched his enterprise in January 1873. First he secured a $25,000 loan from the Owens Lake Silver-Lead Company, giving them a mortgage on his blueprint sawmill and flume, and the assurance that he would always transport their fuel at 25 cents a cord less than he charged Belshaw and Beaudry. Then he built a trail up Cottonwood Creek to his sawmill site at the head of the canyon in the heart of the Sierra timber. Finished in June 1873, the mill was powered by a steam turbine and equipped with a main saw, an edger, and a cross-cut. With logs hauled to it by ox teams, it began turning out lumber for the long flume down the canyon.

By mid-September four miles had been completed; twelve-foot V-shaped sections were boxed together at the mill and sent down the water-filled flume to be attached to the end by carpenters. Temporary sidings were constructed so that the boys could ride the boxes down the flume while the canyon walls echoed to their laughter. The slide was so steep in spots that the workmen shot downward like a cannonball, spraying water in all directions.

Early in November, 1873, the flume reached the Los Angeles bullion trail three miles from the lake shore. Construction was suspended while wagons began hauling cords of wood to Stevens' wharf at Cottonwood Landing. From here the Bessie Brady pulled them in barges across the lake, and the mule teams carried them up the eight-mile "Yellow Grade" to Cerro Gordo. At last those furnaces on Buena Vista's slope had an inexaustible supply of charcoal, and those black columns of smoke continued to darken the sky over the Inyo Range.

But Stevens was only half-finished with his timber empire. In 1874 silver was struck in the Coso Range and the new camp of Darwin was born. At first, mine timbers and furnace charcoal for the new town came from the western slopes of the Coso Mountains, where the pinon pines grew in profusion. From there, hundreds of woodcutters and charcoal-burners sent their products from ten to fourteen miles by burro and wagon into Darwin. By day their charcoal pits smudged the sky over the Cosos; by night their campfires shone as distant sparks to the teamsters and tavern-keepers along the bullion trail. But by 1876 this source, too, was nearly exhausted.

Ready to step into the breach was Col. Sherman Stevens, who reorganized his operation as the Inyo Lumber and Coal Company in April 1876. With J. B. Bond as a partner and a capital stock of $500,000, he first extended his flume to the wharf at Cottonwood Landing. Then in January 1877 he began burning bricks for two charcoal kilns near the wharf. A thirty-two foot tug boat was built in San Francisco, hauled by the Southern Pacific Railroad as far as Mojave, and then carried by Remi Nedeau's teams to Owens Lake. Her engine, also hauled in by mule team, had been taken from the U.S.S. Pensacola, which had foundered in the battle of New Orleans during the Civil War. Afterward she had been towed to New York and rebuilt; her engine now found its way across the continent to Owens Valley.

Anxious to put his steamboat into service, Stevens launched her before she was decked over. In a windstorm one or two nights later she shipped too much water and capsized. With the help of the Bessie Brady Stevens raised her and soon put on a deck. At the suggestion of editor P. A. Chalfant of the Inyo Independent, she was christened the Mollie Stevens, after one of the colonel's two daughters.

By June 1877 Colonel Stevens had spent $64,500 to place his enterprise in full operation. Down from the Cottonwood sawmill the timber was shooting via the thirteen-mile flume. At the charcoal kilns, logs were reduced to charcoal, then hauled in scows across the lake by the Mollie Stevens. From the east shore they were taken on to Cerro Gordo and Darwin by Nadeau's teams.

But misfortune dogged Colonel Stevens and his timber empire. In September 1877 a fire destroyed part of the flume and 64,000 feet of cut logs and lumber-a loss of $5,000 to $6,000. In the same year both Cerro Gordo and Darwin faltered in their output of silver and lead. By '78 they were fading fast as the boys stampeded to the new strikes at Mammoth City and Bodie.

His empire shattered, Colonel Stevens was seventy one when he left Inyo in 1883 to conduct mining operations elsewhere. Returning later, he died at Lone Pine in 1887.

Since then the landmarks he built have disintegrated. The Mollie Stevens, after giving up her engine to the larger Bessie Brady, lay idle by the wharf at Cottonwood Landing till the crystalline waters of Owens Lake destroyed her hull. The Bessie Brady continued to ply the lake with Owens Valley freight till she burned to the water's edge at Cerro Gordo Landing in 1882. High up in Cottonwood Canyon, the sawmill eventually lost its roof but otherwise stood intact for decades, its machinery rusting and silent. Recently a fire destroyed this fine old keepsake of Inyo's silver age. All that remain are the two charcoal kilns, but with holes in the tops they are weathering fast. Unless otherwise preserved they will eventually return to the dust from which they were made by an energetic Inyo pioneer.

Excerpt from Inyo: 1866 - 1966 by the Inyo County Board of Supervisors

Swansea

Cartago

Cerro Gordo

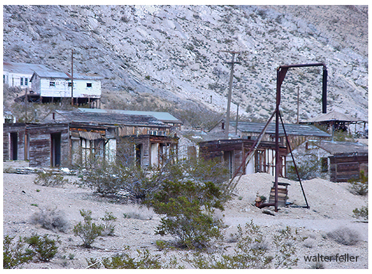

Darwin

Cottonwood flume

photo E.W. Greitkeutz

Courtesy OwensValleyHistory.com/