Chapter III

Native Customs

The Piutes were probably the overlords of eastern California from the beginning of tribal existence until the white men took possession. Their traditions assert that they were at all times the rightful owners. Wars are narrated, Indians from across the Sierras being the traditional invaders. One of the legends told in this book is based on such an invasion. The Owens Valley Indians appear to have returned such visits, for it is said in trans-Sierra counties that they conquered and held as their own the territory about the upper waters of the San Joaquin and Kings rivers. They are classed with the Monosa word said by some to mean "monkey" and by California Blue Book asserted to mean "good-looking." A pioneer writer says the Monos called themselves "Nut-ha."

Three Piute houses - Forbes photo

Bancroft's "Native Races" assigns the westem part of the Great Basin to two "great nations": the Shoshones or Snakes, and the Utahs, both classed as branches of the Shoshonean family, and related to the Apaches. The Piutes (spelled Piutes, Pi Utes, Paiutes, Paiuches, Pah Utes, according to the fancy of the person writing of them) are a subtribe of the Utahs. Bancroft holds that the Piutes and the Pah Utes are two different tribes. The former, split into many small captaincies, have different designations, including the Toy (Tule) Piutes of the Pyramid, Nevada, region; the Ocki (Trout) Piutes on Walker River; the Monos, extending across the Sierras into Tuolumne county ; the Cozaby Piutes, "cozaby" being the Indian name of a small worm found in immense numbers on the shores of Mono Lake and formerly, if not now, used as food.

Eastern Inyo belonged to the Panamints, a subtribe of which the last member is said to have died some years ago. When they were visited by a government representative (F. V. Coville) in 1891 there were about twenty-five survivors. The Indian population there, however, came to represent many tribes, for the remote and nearly inaccessible desert places received renegades, red as well as white, from all directions as the white man's law became enforced.

The name Olancha, now borne by a locality near Owens Lake, designated a tribe living west of that point and across the Sierra summit. Whether that people ever laid claim to territory on this slope is but surmise.

Other neighbors of the aboriginal Owens Valleyans were the Meewocs, in Fresno and the western Sierras; Notonatos, on Kings River; Tularenos, in Tulare ; Kaweahs, and many others. Bancroft gives the names of more than two hundred different tribes in California, with the remark that in many cases the same people took different names, after chiefs or for some other reason.

Note is also found in records of the Franciscan monks, in Bancroft's writings, and in a book written by a French priest in 1860, after spending seven years in the West, of a tribe called the Benemes, inhabiting southern Inyo and the Mojave desert. The only information about them is given by the French writer, Domenich: "The only prominent trait of this numerous tribe is a character of great effeminacy. These Indians are very kind to strangers.

The primitive Piutes were not materially different from the average Indians of other parts of the continent. They lacked some of the attainments of tribes of the eastern seaboard; on the other hand they were higher in the scale than the squalid Diggers of western California, whom they regarded with contempt. They were not warriors, in individual bravery. Their fighting tactics were similar to those of a certain free-lance leader of the Civil War who believed in "gittin' thar fustest with the most men." Overwhelming numbers rather than military skill of any kind seems to have been the chief reliance of Indian combatants.

Spears were known among them, but appear to have been used almost exclusively for fishing. The bow and arrow formed the chief reliance for offense and defense. The Piute bow was commonly made of a tough wood, backed with sinew from deer or other animals. The best form of bow was two and one-half to three feet long, with its ends shaped in short reverse curves. Some bows were simple arcs, four or five feet long. Arrows were made of a species of cane, of the. straightgrowing arrow weed when found, or of willow. Arrow material was cut before it fully matured. Bends in it were straightened by bending in contact with the groove in a stone shaped for the purpose, and heated. Numerous examples of such stones are found in collections of Indian relics. Obsidian was sometimes used for arrow heads; more often the substance employed was the hard wood of the sagebrush, burned or scraped to a dull point. The heads and the two or three spirally placed feathers for guiding the shaft were secured to it by threads of sinew.

Writers on Indian customs have told how obsidian heads for arrow and spear are shaped by being heated, then subjected to the dropping of cold water so as to chip away the stone. Others may have followed this method; the Piute plan was different. The manufacturer selected a chip of obsidian approximating the desired shape and size, and with favorable cleavage lines. This fragment was held in one hand, which was protected by a buckskin covering; then a sharp bit of bone was used to laboriously pry off fragment after fragment of obsidian until a satisfactory point was shaped.

As the food problem took precedence over all others, nearly all Piute manufactures related to it. The bow and arrow, occasionally necessary for fighting, were continually used in hunting. Another article employed in the chase was the rabbit net. A milkweed known to many as Indian hemp yields a long and fairly strong fiber; this was beaten and stripped from the dried stalks and twisted into cord, with which long nets were made. These nets, less than three feet in height, were stretched across favorite runways of rabbits. On the occasion of a drive, the animals coming to the net found no difficulty in putting their heads through the open meshes, but could neither force their bodies through nor, because of their long ears, withdraw from the entanglement, and became easy captives.

Antelope, deer and mountain sheep were sometimes killed by large hunting parties which stealthily surrounded the game; then wherever the hapless animal turned, an arrow awaited it until a lucky shot brought it down.

There were, besides tiny minnows, but two native species of fishes, chubs and suckers. Low water periods were the favorite times for their capture. Dams were made across the diminished stream, sometimes by Indians standing in line across the channel to briefly serve as a backing against which to pile sods, brush and earth. As the channel immediately below was drained, its fish were scooped out. The trout with which the waters of the eastern slope of the Sierras now teem were planted by the white men. Quail also were unknown on the primitive bill of fare, few or none having existed in this region prior to the coming of the whites.

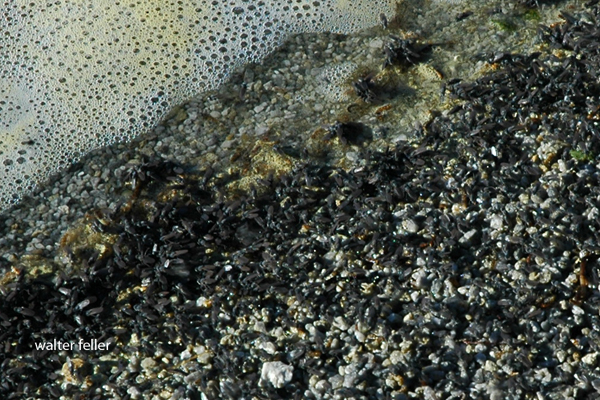

In addition to such foods as white people would find acceptable, the Indian menu included nearly everything that had life, including some kinds of insects and of worms. A large caterpillar known as "pe-ag-ge" (to spell it phonetically) was a staple harvest. The hills between Owens Valley and Mono Lake Basin seem to be the special habitat of this delicacy. It is found in living pine trees, and is not the white worm common in stumps. When gathered it was dried for later consumption. The "cozaby" of the lake shores, the larvae of a form of fly, was gathered where the waves had piled it in windrows at the water's edge, and similarly dried.

Alkali flies along shore of Mono Lake

The sloughs yielded a species of mussel. In the early years of white occupation, piles of such shells were often seen near Indian camps.

Agriculture was an art unknown to the aboriginal inhabitants. They knew that to flood favorable tracts of ground occasionally would increase their yield of plants and grasses, and to that extent only did they pay attention to the fertile soil. A visitor in 1859 wrote:

"Large tracts of land are irrigated by the natives to secure the growth of grass seeds and grass nuts-a small tuberous root of fine taste and nutritious qualities which grows here in great abundance. Their ditches for irrigation are in some cases carried for miles, displaying as much accuracy and judgment as if laid out by an engineer, and this, too, without the aid of a single agricultural implement. They are totally ignorant of agriculture, and depend entirely on the natural resources of the country for food and clothing."The grass nut mentioned in the quotation is known as "Haboose." In appearance it resembles a miniature potato. It is firm and solid, pleasant to the taste, and by no means to be despised as a food article.

The pinon, "Pinus monophylla," to give the tree its botanical designation, furnished to the natives one of their chief food staples. The pine nut is found on most of the desert mountains of western Nevada and eastern California, and in the eastern Sierran range and foothills. Harvesting the nuts, in early autumn, caused, and still causes, an extensive Piute migration to the hills. Whole villages sprang up in the pinon forests while the crop was being gathered. The season comes as the seeds mature, but before the cone scales have opened. The cones are beaten from the trees, and spread in the sun until the scales become dry and crack apart. Artificial heat sometimes expedites this process. The seeds are then shaken out or beaten out with sticks. The nuts were formerly roasted by being put into baskets with live coals and stirred or shaken until the cooking was completed; now probably less primitive means are used. If properly prepared, the nuts remain fresh and edible for long periods. They are eaten either in the roasted condition, or ground up and eaten as a dry meal or made into soup.

Pinon pinecone litter

Many other plants supplied food, either in Owens Valley or in the desert valleys to the eastward, or both, according to where they might be found. Sand grass, a plant of many localities of the West, was one of these. The abundant seeds were gathered in baskets by beating the grass with a sort of paddle; then the chatf was win nowed from the seeds. A large round-headed cactus known as ''devil's pincushion," found in some rocky situations, yielded seeds specially valued because of their long period of freshness after being gathered, thus serving when most other supplies had failed. Several other kinds of seeds were gathered and used, commonly in the form of mush.

A kind of prickly pear was made into food. When, in early summer, the flat, fleshy stems were fully distended with sap, they were broken off with sticks and collected in baskets. Each piece was rubbed with grass to remove the prickles, and exposed to the heat of the sun. When thoroughly dry they kept indefinitely, and were often prepared for eating by boiling. The manner of preparation was sometimes varied. Instead of being dried, the pieces were piled into a thoroughly heated stone-lined cavity, which was first lined with grass. A layer of cactus joints was laid in, then hot stones, then cactus, and so on until the pile was rounded. The whole was covered with a mat of vegetation and lastly with moist earth. The pile was allowed to steam for ten or twelve hours, after which the ''na-vo," as it was called, was ready to be eaten, or to be dried and kept for the future. The dried substance is said to have resembled dried peaches in texture and appearance. This dish was more especially in favor in the eastern part of the county, where the plant is more common.

Some plants of the form botanically known as cruciferae, having large juicy leaves, and having a cabbage-like taste, were gathered and thrown into boiling water for a few minutes, then taken out, washed in cold water and squeezed. This operation was repeated several times, for the purpose of removing bitterness and eliminating some substances known to produce effects unpleasant to the eater. Frank Kennedy, an old-timer in the Panamint region, said that when food was very scarce almost any green herbage was eaten after a similar preparation.

The mesquite furnished for the desert Indians a food not available in Owens Valley. The ripe pods store a small amount of sugary nutritious matter. The same Indians made use of the undeveloped buds of the yucca. In gathering this material, the leaves around the bud were grasped by the hand and by a twist and sidewise pull it was broken off. Though as the buds age the stems become very tough, in that early stage they are brittle and easily broken by one who understands how. In preparing this food, the outer leaves and tips are discarded, leaving an egg-shaped, solid and juicy mass. This is roasted, and eaten either hot or cold.

Indians of Inyo had no such trouble about salt supply as was the rule among eastern aborigines, for they had but to gather all they wanted from huge natural beds.

Sugar substitutes were secured from the common reed, in one of two ways. One was to scrape from the stems and leaves a parasitic covering, which was used in the crude form. White men who saw it say that the "sugar" was filled with small green bugs, a detail apparently not objectionable. Another method was to cut the plants, when fully grown, and dry them in the sun. The material was pulverized and the finer portions sifted out, to be worked into a gum-like mass, and finished by being partially roasted.

Many things were eaten raw; others were dried. The methods of cooking included the simple plan of holding the food on sticks over the fire; roasting by mixing it with live coals in wicker baskets, which were shaken; boiling in water-tight baskets into which hot stones were dropped.

Domestic utensils were made of wickerwork. They were in various forms, according to purpose. Plates and sieves were from nine to twelve inches in diameter, slightly saucer-shaped. Water baskets were so closely woven as to be almost water-tight, and finished off with a coating of pitch or other substance ; these were usually urnshaped, with a narrow neck and often a rounded or conical bottom. The pot basket was the squaw's most useful utensil. It was bowl-shaped, with curving sides and a flattened bottom, very closely woven. Before white men provided something betterit is to be understood that all these references to modes of living relate to the early period -the pot basket served as a container in which to boil food, as well as a bowl for dry substances. On occasion, it served the owner as a head covering. Transportation was done in packbaskets, up to two and one-half feet high, funnel shaped, and carried on the back, sometimes by being grasped by the rim but more often by means of a 'strap which was passed across the bearer's forehead. Winnowing baskets, used for separating chaff from seeds, were two or three feet long, oval with one end brought to a point, and but a few inches deep. The infant Piute was cradled in a wickerwork contrivance with a Y-shaped tree fork as a base. The back of this receptacle was flat; half of the front was rounded, diminishing to the pointed base; usually a curved framework projected from the top of the contrivance to keep the sun from the infant's face. Into this he was lashed, and either left or carried on the mother's back as circumstances required. Other articles, including bird cages, were likewise made of wickerwork.

All these articles were made by the squaws at the cost of much time, care, and often skill. Willow was the principal material, though not the invariable one. In this manufacture, the withes were gathered at a certain stage of growth. The bark was stripped off, and protuberances scraped down. The sticks were then split into three or more strands, unless they were to be used for large and coarse baskets or the withes were too small to justify splitting. Each strand was shaped into a thin pliant strip, which was stored until wanted and soaked in water before using. The thread-like effect in some weaving is secured by the use of a fine and tough grass.

Forbes photo

The finer baskets, such as are included in collections which white people have made, were ornamented in various ways. Bark was sometimes left on for this purpose ; sometimes the work was stained, and on occasion feathers of selected colors were worked in. Colored figuring,, usually black in the baskets of Owens Valley Indians, was made by using natural growths of that hue. The Panamints used a plant known as devil horns, having a black fiber several inches long. Natives who could obtain yucca roots sometimes employed the red coloring from that source.

Clothing was a minor consideration, during most of the year. No attempt was made to manufacture fabrics of any kind. Eabbit skins sewed together served as robes for the women, and provided a warm covering. Moccasins were made of deer skin, put together in the simplest manner. The purpose of these articles was for comfort only; other reasons hardly figured. Early white visitors to this region found the natives clad in little more than primitive simplicity and bright face paints.

A form of glue, for fastening sinew backing on bows, was made by boiling the hoofs of mountain sheep. A minute parasite found on certain plants was also used for the purpose; the parasitic masses were scraped off in the fomi of gum, kneaded and worked, and applied hot.

Stone pipes have been found in some Indian burial grounds, though not often enough to indicate that smoking was more than a ceremonial custom. A plant known as Indian tobacco was used.

Not a single instance has been discovered to indicate that the Piutes had even so much knowledge of metallurgy as to fashion ornaments, let alone articles of use. They knew, however, where placer gold was to be found.

The tribes of the region were not nomadic; the general locality of each subdivision appears to have been fixed with considerable definiteness. In consequence, their habitations were built with fair permanence, considering their limitations of skill. Sometimes the camp consisted of nothing more than a curved windbreak of willow sticks, driven into the ground and fastened by horizontally woven withes. The more elaborate structures were conical campoodies of tules and willows, thickwalled and weatherproof except at the small entrance through which the occupants crouched their way. In the average of these, a person of ordinary height might stand erect in the central part. On occasion, these huts became sweathouses for the treatment of the sick.

PRIMITIVE TRIBES-BOWS AND ARROWS-ABORIGINAL BILL OF FARE-AGRICULTURE AN UNKNOWN FACTOR-NATIVE PLANTS AS FOOD-MODE OF PREPARATION-DOMESTIC UTENSILS-CLOTHING OF MINOR IMPORTANCE-METALLURGY -UNKNOWN HABITATIONS.

Open pinon pinecone

Winnowing pine nuts