Hoover Dam

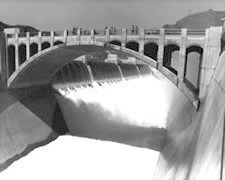

Spillways

Many people who take the tour here at Hoover

Dam want to know when they will get to see the water go over the top of the dam.

Well, the water has never gone over the top of the dam and probably never will.

We don't want the water to go over the top of the dam for a couple of reasons.

First, the power house is located at the foot of the dam. The power house

contains 17 large generators, each producing enough electricity to service about

100,000 people. All that water would be bad for the electrical generators (water

and electricity don't play well together). Second, there are about 18,200

vehicles a day going across the top of the dam, and we don't want those vehicles

to get swept away. The road across the top of the dam is a federal highway, and

it is the shortest way to get from Las Vegas to points east.

Many people who take the tour here at Hoover

Dam want to know when they will get to see the water go over the top of the dam.

Well, the water has never gone over the top of the dam and probably never will.

We don't want the water to go over the top of the dam for a couple of reasons.

First, the power house is located at the foot of the dam. The power house

contains 17 large generators, each producing enough electricity to service about

100,000 people. All that water would be bad for the electrical generators (water

and electricity don't play well together). Second, there are about 18,200

vehicles a day going across the top of the dam, and we don't want those vehicles

to get swept away. The road across the top of the dam is a federal highway, and

it is the shortest way to get from Las Vegas to points east.

Water will probably never go over the top of

the dam due to the spillways. The spillways work just like the overflow hole in

your bathtub or sink at home (if you don't remember seeing that hole, go look

for it right now). If the water ever gets up that high, it will go in the hole

and down the drain, not over the top and onto the bathroom floor (unless, you

have children and they plugged up the hole). The spillways are located 27 feet

below the top of the dam, one on each side of the dam. Any water getting up that

high will go into the spillways then into tunnels 50 feet in diameter, and 600

feet long which are inclined at a steep angle and connect to two of the original

diversion tunnels. Each spillway can handle 200,000 cubic feet per second (cfs)

of water. The flow at Niagara Falls is about 200,000 cfs, so there is the

potential for two Niagara Falls here.

Water will probably never go over the top of

the dam due to the spillways. The spillways work just like the overflow hole in

your bathtub or sink at home (if you don't remember seeing that hole, go look

for it right now). If the water ever gets up that high, it will go in the hole

and down the drain, not over the top and onto the bathroom floor (unless, you

have children and they plugged up the hole). The spillways are located 27 feet

below the top of the dam, one on each side of the dam. Any water getting up that

high will go into the spillways then into tunnels 50 feet in diameter, and 600

feet long which are inclined at a steep angle and connect to two of the original

diversion tunnels. Each spillway can handle 200,000 cubic feet per second (cfs)

of water. The flow at Niagara Falls is about 200,000 cfs, so there is the

potential for two Niagara Falls here.

Each spillway has four steel drum gates, each 100 feet long and 16 feet high. These gates can't stop the water going into the spillway, but they do allow an additional 16 feet of water to be stored in the reservoir. Each gate weighs approximately 5,000,000 pounds. Automatic control with optional manual operation is provided for raising and lowering the gates. When in raised position a gate may be held continuously in that position by the pressure of water against its bottom, until the water surface of the reservoir rises above a fixed point, when by action of a float the gate is automatically lowered. As the flood peak decreases, the gate can be operated manually so as to gradually empty the flood control portion of the reservoir without creation of flood conditions down stream. The spillways have been used twice. The first time, in 1941, was a test of the system. The second time, in 1983, was for a flood.

The Arizona spillway was placed in operation

for the first time on August 6, 1941, soon after the reservoir level had reached

a maximum elevation of 1220.44. The drum gates were raised for several hours on

August 14, 1941, and a hurried inspection revealed that the tunnel lining was

intact, and the inclined portion showed little or no signs of erosion at that

time. Operations were then continued without interruption until the reservoir

level had been lowered to elevation 1205.60 on December 1, 1942. The average

discharge flow through the Arizona spillway during this period was approximately

13,500 cfs with a maximum flow of 38,000 cfs on October 28, 1941, when one of

the drum gates dropped without warning.

The Arizona spillway was placed in operation

for the first time on August 6, 1941, soon after the reservoir level had reached

a maximum elevation of 1220.44. The drum gates were raised for several hours on

August 14, 1941, and a hurried inspection revealed that the tunnel lining was

intact, and the inclined portion showed little or no signs of erosion at that

time. Operations were then continued without interruption until the reservoir

level had been lowered to elevation 1205.60 on December 1, 1942. The average

discharge flow through the Arizona spillway during this period was approximately

13,500 cfs with a maximum flow of 38,000 cfs on October 28, 1941, when one of

the drum gates dropped without warning.

That much water falling 600 feet down a very

steep tunnel caused erosion of the tunnel lining. The eroded area was

approximately 115 feet long and 30 feet wide, with a maximum depth of

approximately 45 feet. The original volume of the cavity was 1069.6 cubic yards.

Repair work was started almost immediately, but because it was believed that

ordinary concrete was not suitable it was decided to utilize the Prepack and

Intrusion process of concrete repair developed by the Dur-ite Company of

Chicago, IL. After repair, the tunnel was polished smooth to help prevent future

erosion.

That much water falling 600 feet down a very

steep tunnel caused erosion of the tunnel lining. The eroded area was

approximately 115 feet long and 30 feet wide, with a maximum depth of

approximately 45 feet. The original volume of the cavity was 1069.6 cubic yards.

Repair work was started almost immediately, but because it was believed that

ordinary concrete was not suitable it was decided to utilize the Prepack and

Intrusion process of concrete repair developed by the Dur-ite Company of

Chicago, IL. After repair, the tunnel was polished smooth to help prevent future

erosion.

During 1983, record flows into Lake Mead were recorded. The record surface elevation was recorded on July 24, with more than two feet of water spilling over the raised spillway gates of Nevada and Arizona. The record flows through the spillway tunnels again caused erosion in the concrete base, which had to be repaired. High water was responsible for wide spread damage throughout the project.

Source - U.S. Department of the Interior - Bureau of Reclamation