Seeing the Elephant

by Anthony Kirkfrom; Rawls, James J., and Richard J. Orsi, editors A Golden State: Mining and Economic Development in Gold Rush California.

In December 1848—the month President James K. Polk precipitated a mad rush west by publicly declaring that rumors of the discovery of a new El Dorado on the far reaches of the continent were true—a struggling young artist named George Holbrook Baker caught the gold fever. Tossing aside his brushes and closing his New York City studio, Baker hurried home to Boston, where he threw in with eleven other "respectable young gentlemen" to form a mining company, the New England Pioneers. "Armed with proper defensive weapons," the adventurers set out for California in early January, having received the admonition of Reuben Lovejoy "to stick to our 'New England Principles' and not to leave one in exchange for every lump of gold taken out."[1]

Traveling by way of New Orleans, the Pioneers crossed the gulf waters on the schooner Nancy Bishop and, after tiding muleback from Vera Cruz to Mazatlán, boarded a steamer for San Francisco. By late June, Baker was working a claim on the North Fork of the American River, one of thousands of enthusiastic young Americans eager to gather the golden harvest of this distant, fabled land. The first day, Baker's labor brought him the grand sum of two dollars. The following day, fortune again eluded him, and on the third day of backbreaking toil he was rewarded with exactly forty cents. A miner, Baker philosophized, was "one who endures many hardships, suffers many privations, and ventures his health, in a measure, for the golden hope of gain, and often it amounts only to that, as some return with injured health and empty pockets." On the Fourth of July, after less than two weeks in the mines, Baker packed up and headed off for Sacramento City, "satisfied," as he put it, "with having seen the '"[2] elephant.

Popular in the mid-nineteenth century, the expression "seeing the elephant" carried a variety of meanings. Following an exhausting forced march across the dreary wastes of western Washoe from the Carson Sink to the Truckee River—the road lined with dead and dying livestock, abandoned wagons and provisions—the Forty-niner Lucius Fairchild wrote in his diary that "that desert is truly the great Elephant of the route and God knows I never want to see it again." Like Fairchild, Americans used the phrase to describe a hardship or an ordeal they had experienced. But more often than not, the Argonauts said they had "seen the elephant" only after making it to the diggings and trying their hand at mining, after coming to realize that golden riches could be won only through hard labor and good fortune and that they had been "humbugged" by reports of treasure for the taking. If the expression, as such, conveyed disappointment, it was a disappointment mixed with other powerful emotions: with the pride of having persevered in the face of countless dangers and difficulties, with the awe of having seen the new country and the mines, with the satisfaction of having had a grand and glorious adventure. Many an Argonaut who used the phrase probably had in mind the old tale of the farmer who upon hearing that a circus had come to town excitedly set out in his wagon. Along the way he met up with the circus parade, led by an elephant, which so terrified his horses that they bolted and pitched the wagon over on its side, scattering vegetables and eggs across the roadway. "I don't give a hang," exulted the jubilant farmer as he picked himself up. "I have seen the elephant." [3]

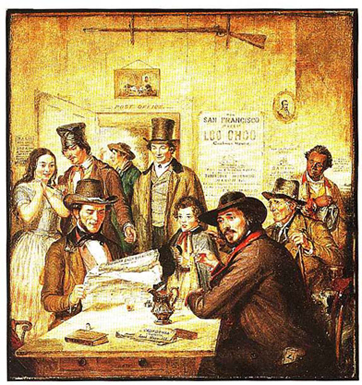

The tremendous excitement associated with the gold discovery was captured on canvas in 1850 by the foremost American genre painter of the age, William Sidney Mount, of Long Island, New York. Reflecting Mount's strong interest in character, California News (plate 1) focuses on the emotions aroused by tales of El Dorado. Wonder and awe and delight animate the faces of young and old, male and female, white and black, as all listen spellbound to an account of the far-off diggings printed in Horace Greeley's New York Daily Tribune . On the rear wall hang posters advertising the departure dates of two California-bound ships, Loo Choo and Sabina , and the sale of "Gold Diggers Outfits."

A celebrated painter, his pictures widely admired in Europe as well as in America, Mount had little incentive to respond to the excitement sweeping the country, apart from preserving the phenomenon in paint. Financially secure, he was largely immune to the gold fever, and, moreover, at forty-three he was perhaps a bit old to join in the rush, which was not only overwhelmingly masculine in character but youthful as well, the average age of the Argonauts being less than thirty. Numerous other artists, however, were caught up in "this extraordinary mania," as the New York Herald of January 11, 1849 described it, and like George Holbrook Baker, they shut their studios and headed off for the land of gold. None had a reputation to equal Mount's, but many were gifted and successful, and together with the countless amateur draftsmen and country painters who flocked to the diggings, they created an engaging pictorial record of what they saw and of what they did, of what it meant to see the elephant.

Among the thirty thousand or so gold seekers who gathered along the Missouri frontier in the spring of 1849—at Independence, at Council Bluffs, at points between—for the march across the Great Plains was J. Goldsborough Bruff. A deep-water sailor in his youth, a former master's mate in the U.S. Navy, and most recently a draftsman for the U.S. Bureau of Topographical Engineers, Bruff commanded a joint-stock company of more than sixty men from Washington, D.C., and environs. Crossing the wide Missouri the first week of June, Bruff kept up the journal of the expedition he had begun earlier, illustrating many of his experiences with pencil drawings and pastels. Particularly charming is his Ferriage of the Platte (plate 2), showing boatmen taking two wagons of the artist's Washington City Company across the river, near its confluence with Deer Creek. Although Bruff and his men made the passage without incident, death by drowning was a surprisingly common occurrence on the California Trail, with the Platte claiming more lives than any other river. In 1849 twenty-eight people lost their lives trying to cross at North Fork, and nearly as many died there the following year. [4]

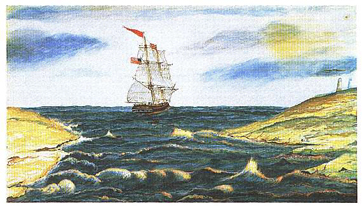

As the overland migrants massed along the muddy Missouri frontier that spring—a great army of gold seekers impatiently waiting for traveling conditions to improve—the first wave of Argonauts who had set out by sea was already in the mines. The first vessel loaded with fortune hunters departed New York shortly after President Polk confirmed the abundance of gold in California, and in 1849 some forty thousand Americans followed one of the sea routes, which would prove far more popular than the overland trail. John Hovey, a laborer from Lynn, Massachusetts, was in the advance guard, taking passage with forty-three other adventurers in the billet-head brig Charlotte , which sailed from Newburyport in January. Once at sea, Hovey opened his journal and painted a handsome, vividly colored image of his ship crossing the bar outside the harbor (plate 3), the beginning of a long voyage around Cape Horn. "This day," he wrote, "we bid adieu to our Dear Native Land, severing the many endearing ties which bind us to our relations and friends, amid the sighs and tears of the fairest portion of mankind and amidst the Cheers and acclamations of about seven hundred male friends who had assembled to witness our Departure for the Golden Land of Cali[fornia]." [5]

For the most part, the Argonauts who followed in Hovey's wake had an easier time of it than the men who traveled the California Trail. The overland route was a journey of more than two thousand miles and some five months, an epic excursion across prairies and mountains and deserts, a test of men and animals, requiring both physical and mental toughness. Those who set out from the Missouri frontier in the greatest migration in the history of the Republic ran a variety of risks. They suffered various diseases, including cholera, which carried away its victims by the score, and such misfortunes as accidental shootings, broken axles, insufficient supplies, and even the occasional Indian attack. By contrast, except for stale water and insect infested food, seasickness, or a bully mate and a bad crew, the greatest hardship endured at sea was often boredom, the terrible tedium of half a year under sail. Argonauts able to afford passage on a clipper ship, those noble greyhounds of the seas that coursed the main at breathtaking speed, could make it to San Francisco in ninety days. They could also shorten the trip by crossing Central America at the isthmus and waiting at Panama City for one of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company's side-wheelers to take them to the golden shore.

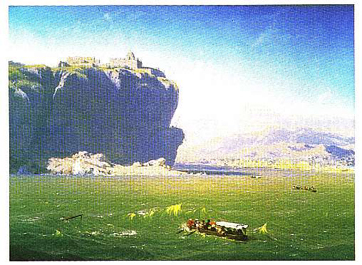

The German-born artist Charles Nahl chose the Panama route when he set out for California in 1851, as did the majority of gold seekers by this date. Nahl, who had arrived in New York by way of Paris two years earlier, was a superb draftsman and among the most able of the artist-Argonauts. Taking the steamer Ohio to Havana in late March, he boarded the Falcon and arrived off the isthmus on April 11. While waiting to go ashore at Chagres he made a pencil drawing that several years later he would work up into a sparkling, meticulously detailed oil showing the ship's launch pulling for shore in the shadow of the storied castle of San Lorenzo (plate 4). Though the Pacific Ocean lay but sixty miles distant from the pestilent port of Chagres, the trip took five days, traveling by boat and muleback, and Argonauts could encounter a variety of dangers—bandits, alligators, poisonous snakes, and fever among them. Despite the hardships Nahl endured, he was profoundly impressed by the sweltering tropical landscape and later wrote home to tell of rank, teeming jungles, of "palms softly waving their branches," of the "screams of monkeys," of a "full moon over the water reflecting swarming beetles and birds." [6]

When Nahl arrived in San Francisco, he lingered but a single night before hurrying off to the diggings. Most Argonauts spent longer, pausing to prepare their outfits for the final push to the mines or to seek out new comrades if contention had splintered the mining company with which they had set out so confidently months earlier. After a long sea voyage, a half year of terrible food and unbearable monotony, it was difficult, as well, for a young man not to succumb to the attractions of San Francisco—the streets lined with lively shops and saloons and crowded with a busy, enterprising, and cosmopolitan people. "The very air is pregnant with the magnetism of bold, spirited, unwearied action," exclaimed the journalist Bayard Taylor, "and he who but ventures into the outer circle of the whirlpool, is spinning, ere he has time for thought, in its dizzy vortex." [ 7]

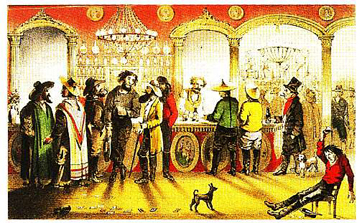

Evenings in California's magnificent metropolis were particularly enchanting, and high-minded and stout-hearted was the Argonaut who did not succumb to the temptation of entering one of the gambling palaces surrounding Portsmouth Square, where in a blaze of light the pleasures of drink and gaming and "bad, lewd" women prevailed. The English-born author, adventurer, and amateur artist Frank Marryat, who arrived in San Francisco in June 1850, caught the barbaric splendor of one of these saloons in a drawing that was reproduced as a hand-colored lithograph in the English edition of his Mountains and Molehills (plate 5). Dazzled as he entered by the brilliance of the huge chandeliers and mirrors, he delighted in the rich furnishing of the room, the gilded ceiling supported by glass pillars, and the walls "hung with French paintings of great merit, but of which female nudity forms alone the subject." Gold was heaped high upon the monte tables, where "dexterous dealers" turned the cards, and above "the din and turmoil of the crowd" sounded the occasional pistol shot. [8]

Unlike the Argonauts who came by sea, the overland emigrants often needed to rest upon their arrival, weary and ragged as they were from the rigors of crossing endless deserts and high-mountain passes. Placerville was a favored spot to gather their strength if they took the Carson River route, or Johnson's Ranch if they traveled the Truckee Trail, which led past the remains of the "cannibal camp" marking the sufferings of the Donner Party. The eight thousand unfortunate Forty-niners who chose Lassen's Cutoff far to the north, which flourished for a single season and added two hundred miles to the trip, had the hardest time of it. Those in the rear found themselves caught in the mountains dangerously late in the year and forced to abandon wagons and belongings in a race for the sheltering Sacramento Valley.

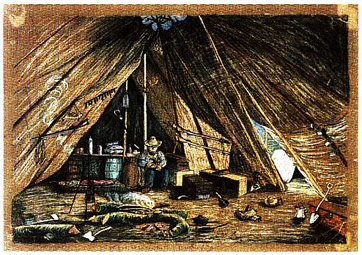

J. Goldsborough Bruff and his Washington City Company were among the last to travel the "Greenhorn Cutoff," as the Lassen route would come to be called. When the party made the strategic decision to divide, Bruff volunteered to remain with two of the wagons while the others took the strongest mules and went for help. Trapped by heavy snows, Bruff suffered through the winter in a primitive lodge constructed of poles covered with heavy cotton sheets—sharing it for a spell with two companions, one of them a four-year-old boy abandoned by his father—and then stumbled out of the mountains, more dead than alive. Despite the ordeal, Bruff kept up his journal and continued to draw. In mid-December he produced a pastel of the lodge (plate 6) where he endured inflamed and painful eyes, fever, rheumatism, and the most miserable of rations, including, one day, a portion of parboiled raven and several old, weathered deer shanks, which, when broiled, provided him with "more carbon & burnt hairs, than nutritious matter." [9]

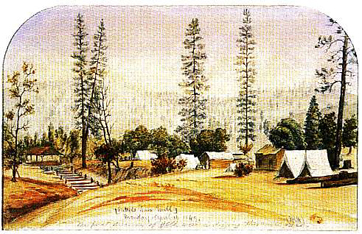

Once safe in California, the hardships of the journey behind them, the overlanders swarmed through the mines, joining the Argonauts who had earlier arrived by ship. Among the first artists to visit the diggings was the surveyor and skilled amateur William R. Hutton. Traveling from San Francisco by way of Sutter's Fort, Hutton reached the community of Mormon Island on April 14, 1849, noting in his diary that the miners were still meeting with success in working the old sandbar in the American River where gold had been discovered the previous March. Curiously indifferent to the commotion all around him—more interested in the flora and fauna than in the gold diggers—Hutton arrived at Sutter's Mill the next afternoon, and on the sixteenth he made a fine watercolor drawing of Coloma, the mining camp that had sprung up around the storied site of James Marshall's discovery (plate 7). It was "a pretty place," he thought, and "thriving," too, composed of some twenty to thirty cabins and numerous tents. "High & bare hills on both sides," he wrote in his diary, "the vally narrow & level; full of tall, straight pines, with some oak, yew & Pinus Sinclairii." [10]

In their quest for riches, the Argonauts streamed through the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, trying their luck at Coloma, at Poverty Hill, at Agua Fria, at Humbug Flat, at countless established communities and secluded camps of their own, wherever a pan of sand and gravel washed in a mountain stream showed sufficient "color." The Philadelphia artist William McIlvaine, Jr., who arrived in the gilded summer of 1849, delighted in the scenery he encountered, particularly the rugged canyons of the Southern Mines, which he thought "extremely wild and picturesque." While tramping the diggings, McIlvaine produced a number of watercolors, including one of two miners working their claim along a gently flowing river (plate 8). But despite the serenity of McIlvaine's evocative image, with its picturesque setting and poetic atmosphere, mining was grueling work. Beginning early in the morning, the Argonauts toiled with pick and shovel, with gold pan and rocker—digging deep into the rocky earth, washing shovel after shovel of soil and sand—as the oppressive sun rose higher and higher in the sky. Exhausted, they broke for the midday repast, then returned to their claims in the afternoon to continue the sweaty struggle until sunset brought blessed relief from the drudgery. "Gold," cautioned the Forty-niner Samuel S. Osgood, "cannot be had by any one who sits still, but he must labor hard—hard as the Irishman who carries the hod or the paver who paves the street." [11]

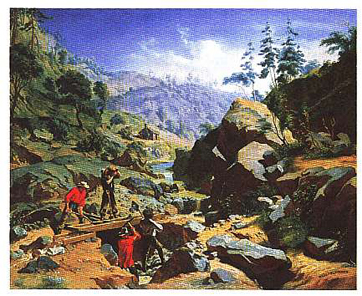

Charles Nahl and August Wenderoth caught the toils of the Argonauts in a painting, Miners in the Sierras (plate 9), which shows four men in a lonely mountain canyon working a claim with a long tom. Nahl and Wenderoth, who had traveled together from New York, knew life in the diggings firsthand, having mined in the spring of 1851 with Charles's brother Arthur near Rough and Ready in Nevada County, and their portrayal of the gold diggers is powerful and authentic, wonderfully suggestive of the colossal labor necessary to wrest riches from the earth. Presumably the artists had some experience themselves with the long tom, an elongated evolution of the rocker, which had come into common use the previous year and which allowed three or four men, working together, to increase their efficiency enormously.

The Argonauts who headed west soon after President Polk electrified the nation with word of the new E1 Dorado often met with surprisingly good luck mining on their own, simply by employing a tin pan to wash golden flakes and nuggets from the sandy loam of a riverbank. The following year, however, good claims became scarce as the shallow placer deposits disappeared. And even before Nahl and Wenderoth started for the land of gold, miners found it imperative to form partnerships and companies in order to make a go of it in the diggings—two or three men to operate a rocker, three or four for a tom, six for two cradles, a dozen for ground sluicing. The increasingly cooperative nature of gold mining, which ultimately evolved into large-scale corporate businesses, is evident in a handsome watercolor executed in 1853 in Calaveras County (plate 10). The work of an unidentified artist, it shows a company of fortune hunters engaged in a river-mining operation, the tall mast of their derrick rising above the rocky outcrop. Although such enterprises could yield incredible riches, they could also result in complete failure or even disaster, with dams and flumes and canals—the work of months—destroyed in an unseasonable storm. As the wise and witty observer who called herself Dame Shirley put it, "Gold mining is Nature's great lottery scheme.[12]

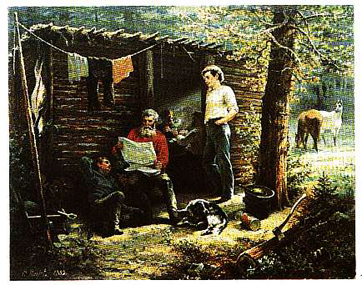

After a day's labor of working a rocker or shoveling pay dirt into a long tom, the miners returned to their camp and prepared the evening meal, with fatigue soon leading them to sleep. For many, the hard, rocky ground was their bed, a canvas tent or rude brush shanty their only shelter. The more industrious Argonauts fitted up snug cabins with comfortable bunks, such as the New York-born artist Henry Walton depicted in his meticulously detailed watercolor William D. Peck, Rough and Ready, California (plate 11). Though far from home and loved ones, such accommodations were the setting for many an agreeable evening, with several miners indulging themselves in the simple pleasures of a companionable meal, pipes, and conversation. The same surroundings could, however, be the scene of sorrow and sickness and death, as related by a Forty-niner in a letter rich with imagery and human emotion. "Imagine to yourself," he wrote, "three persons in a lonely cabin situated in a deep ravine, the rain pouring down, a dark night, and nothing to be heard save the pattering rain and the barking of coyotes; one of the three lying in the worst stages of the smallpox, his face and hands almost as black as coal; the sick one in the last hour of his life and the other two sitting by, watching in silence for the last of earth; then you can see us as we passed the night of the fourth of January, 1853, in Dragoon Gulch, California.[13]

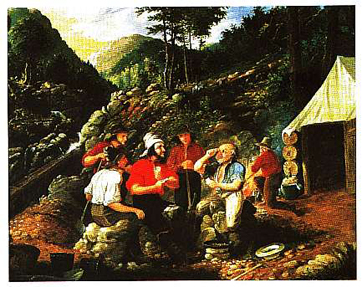

As a relief from the drudgery of their long days, the boredom, the frequent disappointment, miners sought out recreation whenever opportunity arose. Alburtus Del Orient Browere, who arrived in California in 1852 from his home in Catskill, New York, produced an animated portrait of miners enjoying a spirited game of cards at day's end (plate 12). The pleasures of cards and tobacco were innocent enough, but many of the men who labored six or seven days a week succumbed to more serious vices. "Gambling, drinking & houses of ill-fame are the chief amusements of the country," declared Lucius Fairchild in the summer of 1850, though he was quick to add that he did "not frequent such places." Sunday was invariably the great day to seek out the amusements of town, as all miners attested, often with surprise or shock. "In the morning," wrote Enos Christman of Sonora, "we have public auctions, in the afternoon the bullfight and the circus and Dr. Collier's troupe of Model Artists, together with numerous fandango rooms, dance houses, and scores of gambling hells.[14] Many Argonauts, by contrast, held fast to traditional values and spent the Sabbath quietly—reading passages from the Bible, washing clothes, writing letters home, soaking up the wild, mountain beauty of their Sierra Nevada home. The talented French-born artist-Argonaut Ernest Narjot ably developed the theme of Sunday as a day of companionable relaxation in Miners: A Moment at Rest (plate 13), a painting executed some thirty years after he himself had mined for gold at Fosters Bar on the Yuba River.

Despite high hopes of bright fortune smiling upon them, the freedom and independence of the new country, the lusty pleasures of San Francisco and the mining towns, rare was the Argonaut whose thoughts did not regularly drift homeward to family and loved ones. "I am a stranger in a strange land," wrote William Swain to his wife in February 1850, "with the bonds of friendship, the endearments of the home of youth and the fond ties of kindred all exerting their influences upon me, and like the pole to the needle, they attract all my thoughts and preferences back to the land of my home and family." Etienne Derbec, an astute French observer of life in the mines, declared that homesickness gripped all the miners, and that "when they stretch out at night on the hard earth, their backs broken by the day's labors, they think about the bed on which they used to rest so comfortably." Many of them thought, as well, of the fond embrace that awaited them so far away, as poignantly portrayed in an oil painting by an unknown artist that dates to the age of gold (plate 14). "Oh, Matilda," moaned the Forty-niner David Dewolf in the summer of 1850, "oft is the night when laying alone on the hard ground with a blanket under me and one over me that my thoughts go back to Ohio and I think of you and wish myself with you."[15]

Few Argonauts gathered the golden harvest they set out so confidently to reap. Many returned home after a single unsuccessful season in the mines, satisfied with having seen the elephant, while others stayed on a year or two or more, finding it difficult to overcome their pride and admit defeat. But, ultimately, unless they remained and became Californians, they packed up and headed home—to Pennsylvania or Massachusetts or Iowa or Georgia, to the glad welcome portrayed in Alburtus D. O. Browere's sentimental painting The Miner's Return (plate 15), executed in 1854, two years before the artist took himself back to Catskill, New York. For the most part, though, whether they made their "pile" or returned empty-handed, the Argonauts came to glory in the grand adventure of their splendid, vigorous youth. The Forty-niner Richard Lunt Hale appeared in his hometown of Newburyport, Massachusetts, in the spring of 1854, bronzed and bearded, but without the riches he had set out for more than four years earlier at the age of twenty-two. His odyssey had taken him to El Dorado, where he mined on the Yuba River and at Murphys Camp, as well as to Portland and the Oregon Territory. Despite failure, Hale realized "that my experiences had been as valuable to me as the bag of gold I had come home without. The gold might easily vanish, but that which I had gained in pursuing the 'pot of gold at the end of the rainbow' could never be taken away."

8— Seeing the Elephant

1. An unidentified Boston newspaper and Reuben Lovejoy are quoted in George H. Baker, "Records of a California Journey," Quarterly of the Society of California Pioneers 7 (December 1930): 218, 220.

2. George H. Baker, "Records of a California Residence," Quarterly of the Society of California Pioneers 8 (March 1931): 46-47, 48.

3. Joseph Schafer, ed., California Letters of Lucius Fairchild (Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1931), 34. The story of the farmer, which has appeared in various versions over the years, is taken from Time-Life Books, The Forty-niners (New York: Time-Life Books, 1974), 80. Numerous examples of how the Argonauts used the phrase can be found in the Foreword to John Phillip Reid, Law for the Elephant: Property and Social Behavior on the Overland Trail (San Marino, Calif.: Huntington Library, 1980), ix-x.

4. John D. Unruh, Jr., The Plains Across: The Overland Emigrants and the Trans-Mississippi West, 1840-60 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1979), 409. For Bruffs diary, richly illustrated with his drawings, most of which are at the Huntington Library, see Georgia Willis Read and Ruth Gaines, eds., Gold Rush: The Journals, Drawings, and Other Papers off Goldsborough Bruff , 2 vols. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1944).

5. John Hovey, "Journal of a Voyage from Newburyport, Mass. To San Francisco, Cal., in the Brig Charlott[e]," January 23, 1849, Huntington Library. I have introduced punctuation into the passage for the benefit of the reader.

6. Charles Nahl to his father and stepmother, Sacramento, February 3, 1852, quoted in Moreland L. Stevens, Charles Christian Nahl, Artist of the Gold Rush, 1818-1878 (Sacramento: E. B. Crocker Art Gallery, 1976), 34.

7. Bayard Taylor, Eldorado, or, Adventures in the Path of Empire , 2 vols. (New York: George P. Putnam, 1850), vol. 1, 114.

8. Frank Marryat, Mountains and Molehills: or, Recollections of a Burnt Journal (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1855), 42, 45.

9. Read and Gaines, Gold Rush , vol. 2, 671.

10. William Rich Hutton, Glances at California, 1847-1853 (San Marino, Calif.: Huntington Library, 1942), 11. Hutton's drawings and watercolors, together with his diaries and letters, are at the Huntington Library.

11. William McIlvaine, Jr., Sketches of Scenery and Notes of Personal Adventure, in California and Mexico (Philadelphia: Smith & Peters, Printers, 1850), 19; New York Daily Tribune , June 22, 1849.

12. Carl I. Wheat, ed., The Shirley Letters from the California Mines, 1851-1852 (New York: Knopf, 1949), 136. In November 1852, seven months after she wrote the letter quoted from, Dame Shirley noted that the thirteen men of the American Fluming Company, which had turned a branch of the Feather River out of its bed, had been rewarded with $41.70 in gold dust for their summer's labor.

13. Enos Christman, One Man's Gold: The Letters & Journals of a Forty-Niner , ed. Florence Morrow Christman (New York: Whittlesey House, 1930), 276. Dragoon Gulch was located near the mining town of Sonora.

14. Schafer, California Letters of Lucius Fairchild , 71; Christman, One Man's Gold , 179

15. William Swain and David Dewolf are quoted in J. S. Holliday, The World Rushed In: The California Gold Rush Experience (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1981), 329, 353; A. P. Nasatir, A French Journalist in the California Gold Rush: The Letters of Etienne Derbec (Georgetown, Calif.: Talisman Press, 1964), 121.

16. Carolyn Hale Russ, ed., The Log of a Forty-Niner (Boston: B. J. Brimmer, 1923), 180.

Rawls, James J., and Richard J. Orsi, editors A Golden State: Mining and Economic Development in Gold Rush California. Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press, c1999 1999.

Prospectors & Miners

Pioneers

"Seeing the Elephant," a mid-nineteenth-century lithograph designed by Wm. B. McMurtrie. Printed and published by Benjamin F. Butler. California Historical Society, FN-30610.

Plate 1. William S. Mount, California News , 1850. Oil on canvas, 21 ½ × 20 ¼ in. Courtesy Museums at Stony Brook, New York; gift of Mr. and Mrs. Ward Melville .

Plate 2. J. Goldsborough Bruff, Ferriage of the Platte , 1849. Pastels on paper, 8 × 11 3/8 in. Courtesy Huntington Library, San Marino, Calif .

Plate 3. John Hovey, Brig Charlotte Crossing N[ewbury] P[ort] Bar , 1849. Gouache and watercolor on blue paper, 7 ½ × 13 ¼ in. Courtesy Huntington Library, San Marino, Calif .

Plate 4. Charles C. Nahl, Boaters Rowing to Shore at Chagres , 1855. Oil on tin, 9 ¼ × 12 in. Collection of Oscar and Trudy Lemer. Photograph courtesy Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento .

Plate 5. Frank Marryat, The Bar of a Gambling Saloon . From Frank Marryat, Mountains and Molehills: or, Recollections of a Burnt Journal , 1855. California Historical Society .

Plate 6. J. Goldsborough Bruff, W. End of Lodge before the Snow Storm , 1849. Pastels on brown paper, 11 × 16 ½ in. Courtesy Huntington Library, San Marino, Calif .

Plate 7. William R. Hutton, Sutter's Saw Mill , 1849. Watercolor and pencil on paper, 6 × 9 in. Courtesy Huntington Library, San Marino, Calif .

Plate 8. William McIlvaine, Jr., Panning Gold, California , undated. Watercolor over graphite on paper, 18 5/8 × 27 ½ in. Courtesy M. & M. Karolik Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston .

Plate 9. Charles C. Nahl and August Wenderoth, Miners in the Sierras , 1851-1852. Oil on canvas, 54 ¼ × 67 in. Courtesy National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution; gift of the Fred Heilbron Collection .

Plate 10. Unidentified artist, Washing Gold at Calaveras River , 1853. Watercolor and gouache on paper, 16 1/8 × 22 in. Courtesy M. & M. Karolik Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston .

Plate 11.

Henry Walton, William D. Peck, Rough & Ready, California , 1853. Watercolor

on paper, 11 × 13 ¼ in. Courtesy Oakland Museum of California .

Plate 11.

Henry Walton, William D. Peck, Rough & Ready, California , 1853. Watercolor

on paper, 11 × 13 ¼ in. Courtesy Oakland Museum of California .

Plate 12. Alburtus D. O. Browere, Goldminers , 1858. Oil on canvas, 29 × 36 in. Courtesy Anschutz Collection, Denver .

Plate 13. Ernest Narjot, Miners: A Moment at Rest , 1882. Oil on canvas, 39 3/8 × 49 3/8 in. Courtesy Autry Museum of Western Heritage, Los Angeles .

Plate 14. Unidentified artist, The Miner's Dream , undated. Oil on canvas, 36 × 44 ½ in. Courtesy Society of California Pioneers .

Plate 15. Alburtus D. O. Browere, The Miner's Return , 1854. Oil on canvas, 24 × 30 in. Collection of Everett Lee Millard. Photograph courtesy Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento .