https://mojavedesert.net/mining-history/leadfield/index.html

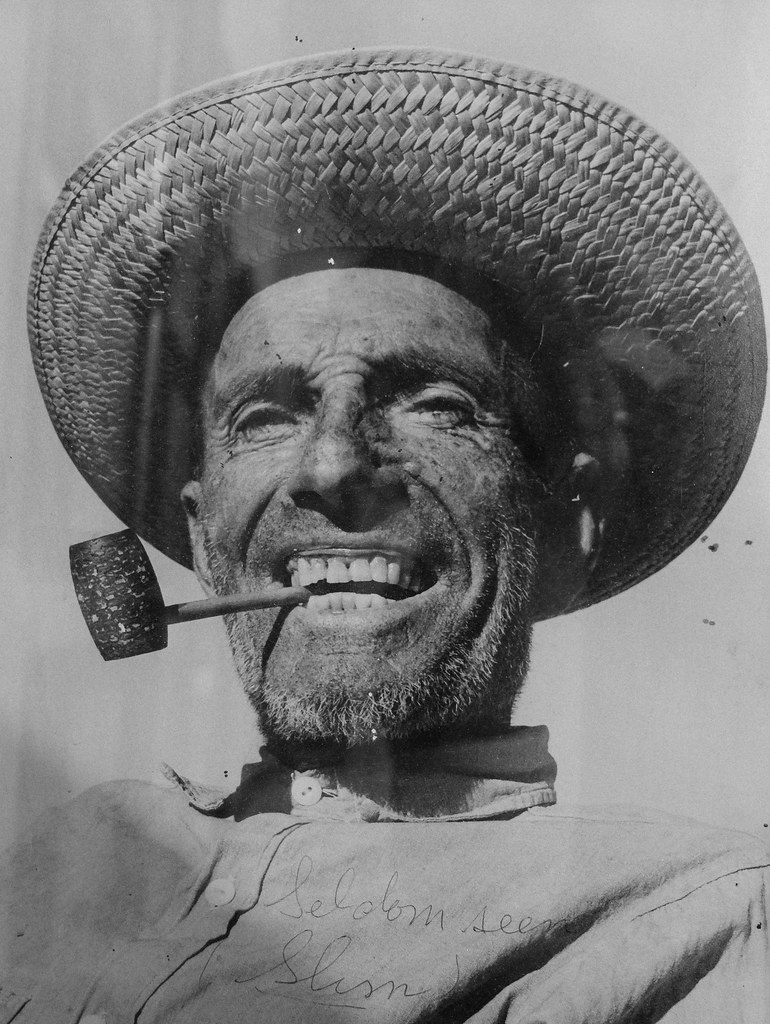

Leadfield, located in Titus Canyon, was promoted by a man who could have sold ice to an Eskimo. He blasted some tunnels and liberally salted them with lead ore and drew up some enticing maps of the area, which lured Eastern promoters into investing money.

The true story of Leadfield is somewhat different from the usual tale of a stock swindle and a dying town.

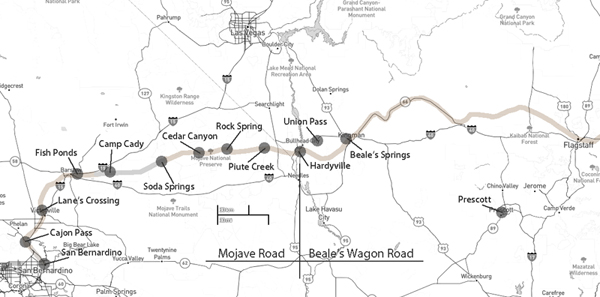

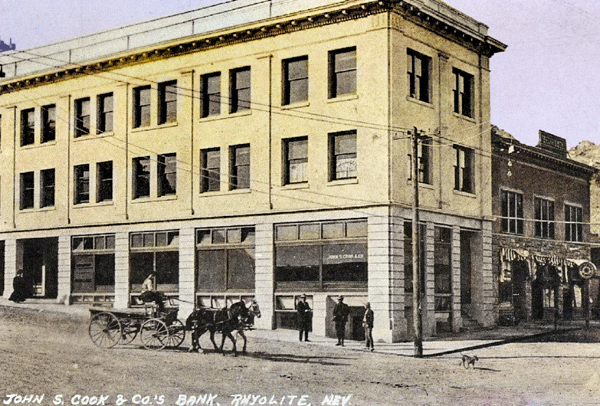

During the early days of the Bullfrog boom, W. H. Seaman and Curtis Durnford staked nine lead and copper claims in Titus Canyon and came into Rhyolite with ore samples that assayed as high as $40 to the ton. The Death Valley Consolidated Mining Company was incorporated and immediately began a development and promotional campaign.

The Death Valley Consolidated Mining Company ceased operations in 1906 after realizing that the long and arduous trip between its mine and Rhyolite made the shipment of its ore absolutely unprofitable.

In 1924, three prospectors staked out numerous claims on some lead deposits in Titus Canyon. A local promoter named John Salsberry purchased twelve claims from the three prospectors and formed the Western Lead Mines Company.

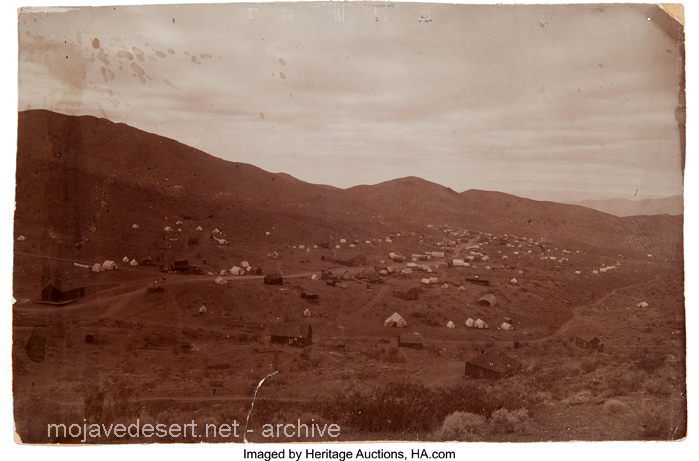

The young camp was entering the boom stage, and by January 30th, half a dozen mining companies were in operation. The stock of Western Lead Mines Company soared to $1.57 per share.

Eastern California, and especially Inyo County, was long overdue for a mining boom. With the backing of a successful and skilled promoter, Leadfield seemed assured of obtaining the necessary financial support to take it from a prospecting boom camp into a producing mine town.

The Inyo Independent greeted Julian with a glowing description of his character and abilities, but a different endorsement would be printed in later years.

The boom was now on in earnest, with the Western Lead Company employing 140 men and the Titus Canyon Road being completed. The Western Lead Mine produced 8% to 30% lead and seven ounces of silver per ton.

The California State Corporation Commission was not so impressed with the company and raised the righteous indignation of local folk. The local attitude was well summed up by the Owens Valley Herald: “The Commission is using its every endeavor to try and prejudice the people against this latest promotion of Julian’s.”

The paper pointed out that Julian was not trying to swindle anyone and that he had publicly invited any reputable mining engineer worldwide to visit the Leadfield District. The paper concluded that the future of Leadfield seemed very bright.

Julian was not the only promoter singing the praises of the Leadfield District, for numerous other companies were also trying to cash in on the boom. The Western Lead Mines Company, Julian’s pet, led the pack, with one of its tunnels six hundred feet inside the mountain.

The town of Leadfield was trying to keep pace with the boom and announced that a large hotel would soon be built. On March 15th, the first of Julian’s promotional excursions pulled into Beatty, and 340 passengers were served a sumptuous outdoor feast by the proprietor of the local Ole’s Inn.

Lieutenant-Governor Gover of Nevada gave the keynote speech, and Julian gave a speech praising Julian for overcoming the numerous obstacles that modern governmental bureaucracies put in a man’s path. The trip was a big success, and Western Lead stock advanced 25 on the San Francisco market the next day.

Western Lead stock had soared to $3.30 a share by the end of March, and several ore-buying and smelting concerns sent representatives to the district to discuss reduction and smelting rates.

Leadfield continued to develop in the months following the great train excursion. New mining companies opened for business, and the Tonopah & Tidewater Railroad replied that definite plans for a railroad spur into Leadfield had not been made as the present business does not warrant its construction.

The townsite of Leadfield was officially surveyed on April 30th, and the town’s plat was submitted to Inyo County officials for approval. The town was platted on land donated by the Western Lead Company.

The State of California was breathing hard upon Julian’s neck, and the Corporation Commission hauled a brokerage company into court for selling Western Lead stock without a state permit. Expert witnesses testified that the Western Lead Mine was a quite legitimate proposition.

The continued investigations by the state of California hurt the sales of Western Lead stock, and another factor began to take a toll. Julian’s credibility began to shrink, and the company never recovered from the panic that set in.

Julian bought into the New Roads Mining Company, which gave him control of the two largest mines of Leadfield and announced plans to construct a large milling plant at Leadfield.

As summer approached, the Leadfield boom showed no signs of peaking. The California Corporation Commission ordered that sales of Julian’s personal stock in the Western Lead Mines must immediately cease on the Los Angeles stock exchange due to evidence introduced at a hearing.

Despite the heavy blow to Julian’s financial fortunes, developments at Leadfield proceeded, and the Mining Journal printed a long, detailed report on the Leadfield District in July, which helped to restore public confidence.

The mines agreed with the independent experts and continued to work, and the Boundary Cone Mining Company ordered a new 25-horsepower hoist and headframe and increased its workforce to twelve miners.

In late July, the Western Lead Mining Company brought a $350,000 damage suit against the Los Angeles Times and the California Corporation Commission. Still, the suit was quickly thrown out of court for insufficient cause. In August, a new mining company, the Pacific Lead Mines No. 2, was incorporated.

During September and October, drilling and tunneling continued in Leadfield’s mines, but in late October, two events took place that spelled the end of Leadfield. The main tunnel of the Western Lead Mine finally penetrated the ledge but found almost nothing.

At almost the same time, the California Corporation Commission dealt Julian another blow when it halted stock sales in the Julian Merger Mines, Inc. Julian’s empire fell apart. The other mines slowly closed, one after the other, and Leadfield became a ghost town in a matter of months.

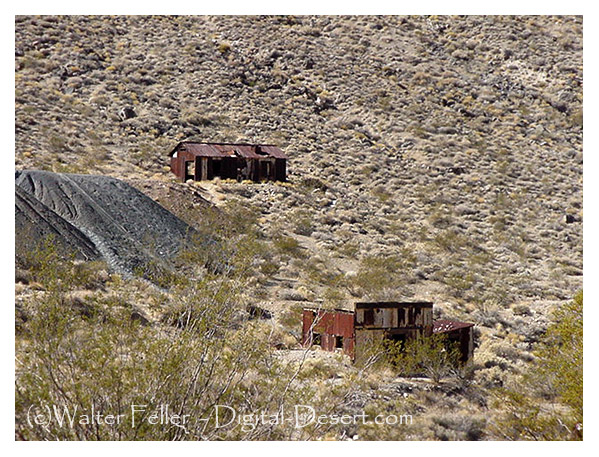

The failure of a mining district led to a flurry of lawsuits. In February of 1927, the Western Lead Company removed its heavy machinery and the pipeline to a mine that the company owned in Arizona.

Julian went on to organize the Julian Oil and Royalties Company and was indicted for fraud, but jumped bail and committed suicide.

Leadfield was a ghost town created by C. C. Julian. Still, the existence of lead ore in the district had been known as far back as the Bullfrog boom days of 1905, and the California Corporation Commission allowed companies other than Julian’s to sell their stock.

Julian did not start the Leadfield boom and had plenty of help in supporting the boom once it had started. The citizens of Inyo County, California, and Nye County, Nevada, also supported the mines.

The collapse of Julian’s financial structure came at the worst possible time for Leadfield. Although it seems doubtful that Leadfield had enough ore to support more than a small mining company or two, indications are that without the sudden panic of the fall of 1926, that mine or two could have survived.

The Titus Canyon Road, an engineering marvel, was built by Julian and cost an estimated $60,000 to build. Without Julian, the road would not have been finished, and today presents one of the most spectacular routes in Death Valley National Park.